Kenya’s Debt Sustainability Note

By Research Team, Oct 20, 2019

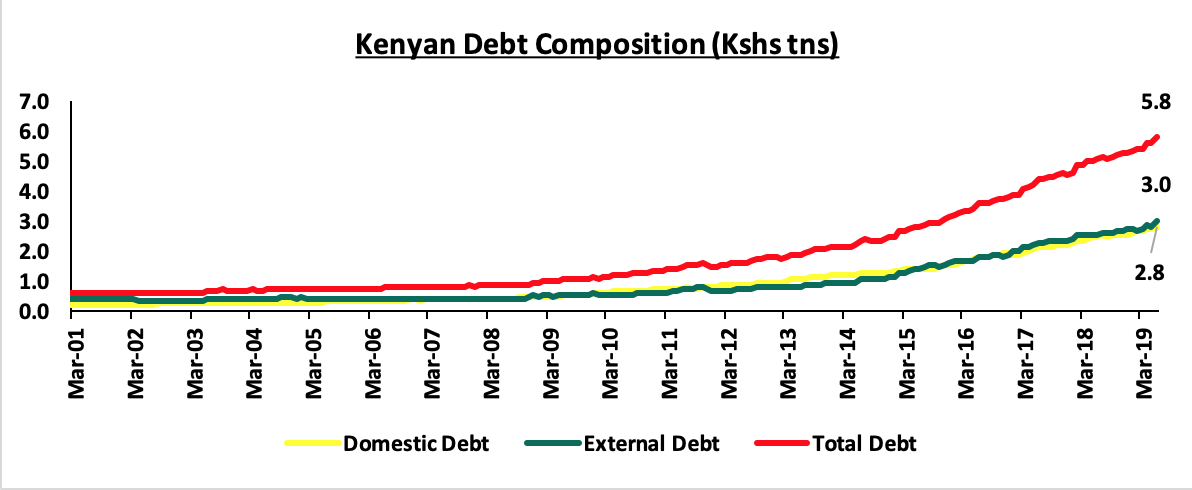

The National Assembly on 9th October 2019 voted to amend the Public Finance Management (PFM) Regulations as proposed by the Treasury to substitute the debt ceiling that was previously pegged at 50.0% of GDP to an absolute figure of Kshs 9.0 tn. According to the Acting Cabinet Secretary, Ukur Yattani, the move was driven by the need to provide clarity in terms of controls and real-time oversight mechanism on the growth of public debt and safeguard Kenya’s public debt at sustainable levels as per the Constitution. As at June 2019, the total public debt stood at Kshs 5.8 tn, with 48.0% of this being domestic debt at Kshs 2.8 tn and 52.0% being foreign debt at Kshs 3.0 tn, against a debt strategy target mix of 60% foreign and 40.0% domestic debt as highlighted below:

Source: Central Bank of Kenya

In this note, we will focus on the level of debt in Kenya and whether it remains sustainable, where we will look at:

- The Evolution of Kenyan debt,

- Debt Servicing and Impact of the Current Debt Levels to the Economy,

- We shall review what is considered sustainable levels and our view going forward.

- The Evolution of Kenyan Debt:

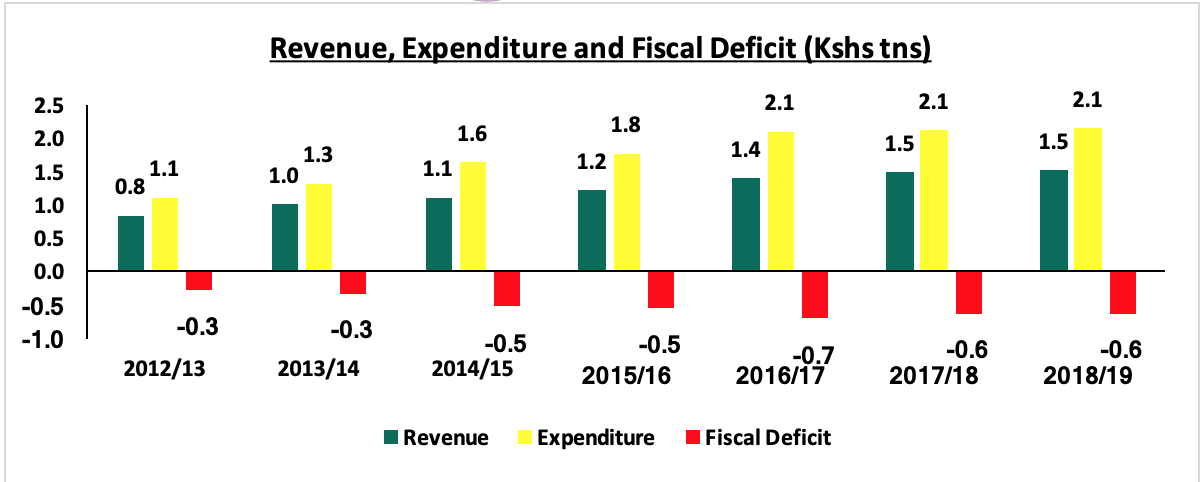

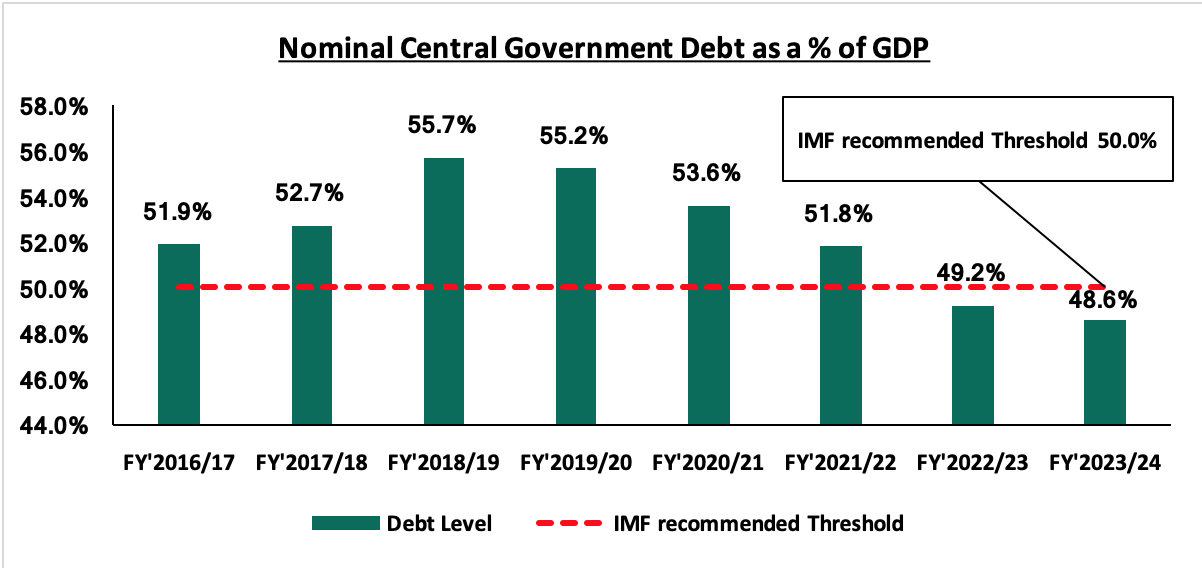

Over the years, we have seen the national budget continue to grow with the total expenditures growing at a CAGR of 11.5% to Kshs 2.1 tn in FY’2018/19 from Kshs 1.1 tn in FY’2012/13, while revenue growth has increased at a CAGR of 10.3% to Kshs 1.5 tn in FY’2018/19 from Kshs 845.1 bn in FY’2012/13. The faster increase in expenses as compared to revenue necessitated that the difference be funded through borrowing. This has led to an increase in the debt level from 42.1% debt to GDP in 2013 to the current estimated level of 60.2%. According to the IMF, the target debt to GDP for developing countries should be at or below 50.0%, meaning that the current debt level in the country has surpassed the standard set by the global lender, and this may pose fiscal challenges if mechanisms are not put in place to improve on Kenya’s fiscal and public finance management framework.

Source: National Treasury

There are two avenues that the government can use for borrowing, either from the domestic markets through issuance of treasury bills and bonds, or can seek to borrow from the international markets through direct government-to-government negotiations or from the international capital markets through the issuance of sovereign bonds/Eurobonds. Raising funds from the domestic market is much easier and faster and there is already a defined timetable for this i.e. weekly through treasury bills and monthly through treasury bonds and for this, the Central Bank acts as the borrowing agent of the Treasury. The main issue with domestic debt is that government competes with the private sector for funds from banks which leads to crowding out of private sector and slowdown in economic growth as the contribution by the private sector to economic growth reduces. On the foreign borrowing, though it gives the government another borrowing avenue apart from the domestic market, the challenge is that it opens up the country to trends in the global market, which may destabilise the economy in times of global crisis.

|

External Debt by Creditor Type (Kshs Million) |

|||||||

|

Creditor type |

Jun-13 |

Jun-14 |

Jun-15 |

Jun-16 |

Jun-17 |

Jun-18 |

CAGR |

|

Bilateral |

217,970 |

248,636 |

405,562 |

491,864 |

669,840 |

759,017 |

28.3% |

|

Multilateral |

507,920 |

593,397 |

680,192 |

794,797 |

839,721 |

825,299 |

10.2% |

|

Commercial Banks |

58,928 |

234,799 |

276,937 |

432,377 |

634,109 |

830,652 |

69.8% |

|

Suppliers Credits |

15,207 |

16,452 |

16,628 |

16,628 |

15,303 |

16,725 |

1.9% |

|

External Debt |

800,025 |

1,093,284 |

1,379,319 |

1,735,666 |

2,158,973 |

2,431,693 |

24.9% |

The country debt mix currently stands at 52:48 for external and domestic debt. According to figures from the latest public debt report by the National Treasury as highlighted in the table above, Kenya, has continued to evolve from a system of bilateral and multilateral development institutions to a much more commercial funding structure comprising of Eurobonds and syndicated loans. This has seen the proportion of Bilateral and Multilateral debt, which stood at 90.7% of total external debt as at June 2013, declining to approximately 65.2% as at June 2018, despite a 16.9% CAGR on the Bilateral and Multilateral loans combined. Commercial loans which are deemed to be more expensive than the soft loans from bilateral and multilateral development institutions have on the other hand grown by a CAGR of 69.8% from a low of Kshs 58.9 bn as at June 2013 to Kshs 830.7 bn as at June 2018, equivalent to 34.2% of total foreign debt.

- Debt Servicing:

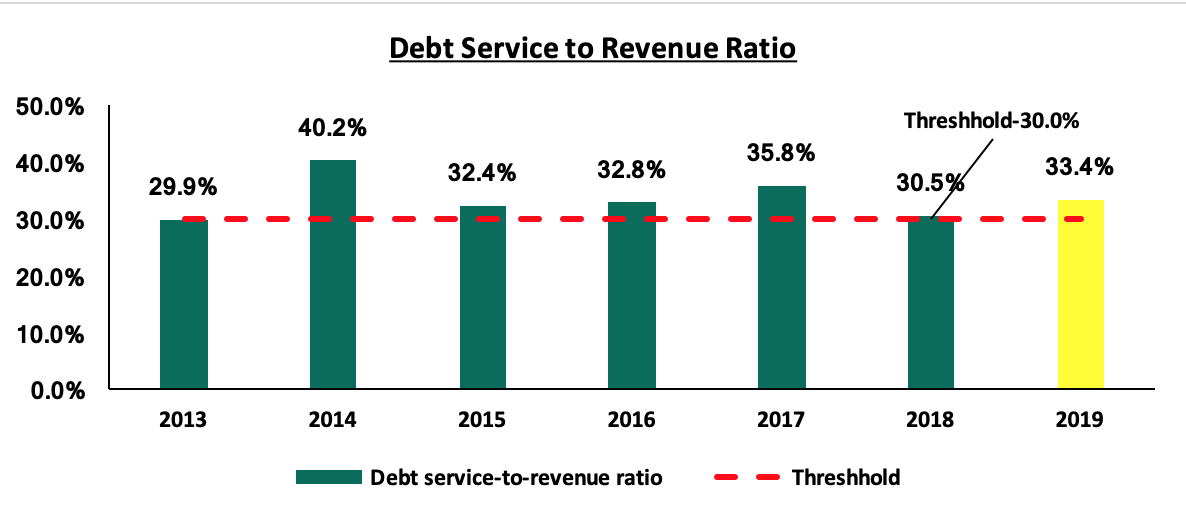

One of the key elements of debt sustainability in any economy is the ability to service it, and this is usually measured by revenue collection to total outstanding payments required, both in principal and interest payments. Debt is necessarily not bad provided the country has the ability to refinance it without negatively affecting the functioning of the country. The government at times borrows to pay off maturing debt, but this is akin to borrowing from Peter to pay Paul, as it does not lead to economic growth, while the debt obligations are postponed to a further date in the future. A country that is able to pay off their debt with revenue collection is the ideal situation. According to the National Treasury Annual Public Debt Report, the debt service-to-revenue ratio is estimated to hit 33.4% as at the end of 2019, which is higher than the recommended threshold of 30.0%. Going forward however, risks are abound due to the high rate of accumulation of new debt. With the recommended threshold already breached, the country faces risks of repayment in the event of shocks or lower than expected revenue collection.

Below is a chart of the debt service to revenue from 2013 with expected levels for 2019:

Source: IMF Country Report & National Treasury Annual Public Debt Report

Using a case study of Zambia, to illustrate the risks abound due to high levels of debt, the country has seen its 10-year Eurobond issued in 2012 trading at highs of 22.0%, in 2019, 20.0% points more than U.S. Treasuries of an equivalent maturity, with similar dollar spreads and yields only being recorded in nations already in default globally, such as Venezuela. The performance has mainly been due to concerns of a widening fiscal deficit and deteriorating credit worthiness on the back of high debt levels estimated at 78.1% of GDP as at the end of 2018, which has seen Credit rating agency Moody’s downgrade Zambia’s long-term issuer ratings to Caa2 from Caa1 and changed the outlook to negative from stable. This was in addition to the three downgrades by the same agency in 2018. The downgrade is a reflection of increased liquidity and external pressures, which has elevated the risk of default over the near-term due to the impairment of the government’s ability to service its debt over the medium term. The country’s external position is currently vulnerable to external shocks due to narrow foreign exchange reserve buffers that have declined from 4.7 months of import cover in 2015 to 1.7 months of import cover in May 2019. The declining reserves have been attributed to the significantly high external government debt service, with the country’s debt service to revenue ratio estimated at 71.2% as at 2018, a rise from 57.8% as at 2017, coupled with a high current account deficit. The depletion of their forex reserves due to the high foreign debt refinancing has also taken a toll on the country’s currency making the cost of financing the foreign denominated debt even more expensive.

- What is considered sustainable levels? and our view going forward:

The ballooning public debt in the country has become a major concern and the trend is worrisome as the economy is likely to face fiscal challenges in the near future. This has been echoed by various authoritative bodies, with indications currently pointing to a possible further downgrading of Kenya’s creditworthiness currently at ‘B2 stable’ by the global rating firm Moody’s following the completion of their periodic review on Kenya, where they raised concern over the country's very low fiscal strength, ballooning debt and rampant corruption. Some of the factors that has led to the acceleration in government borrowing include;

- Slow growth in revenue collection compared to the expenditure growth: As discussed earlier, total expenditures growing at a CAGR of 11.5% to Kshs 2.1 tn in FY’2018/19 from Kshs 1.1 tn in FY’2012/13, while revenue growth (KRA Tax collections) has increased by a CAGR of 10.3% to Kshs 1.5 tn in FY’2018/19 from Kshs 845.1 bn in 2012/13. This has seen the budget deficit growing at a CAGR of 14.9% to Kshs 624.2 bn in FY’2018/2019 from Kshs 271.9 bn in FY’2012/2013 with the deficit being reflected in the increment in the levels of debt, and

- Significant investment in infrastructure projects: Though investment in infrastructure will eventually result in an increase in economic activity, it will take time for the economy to start benefitting from such investments.

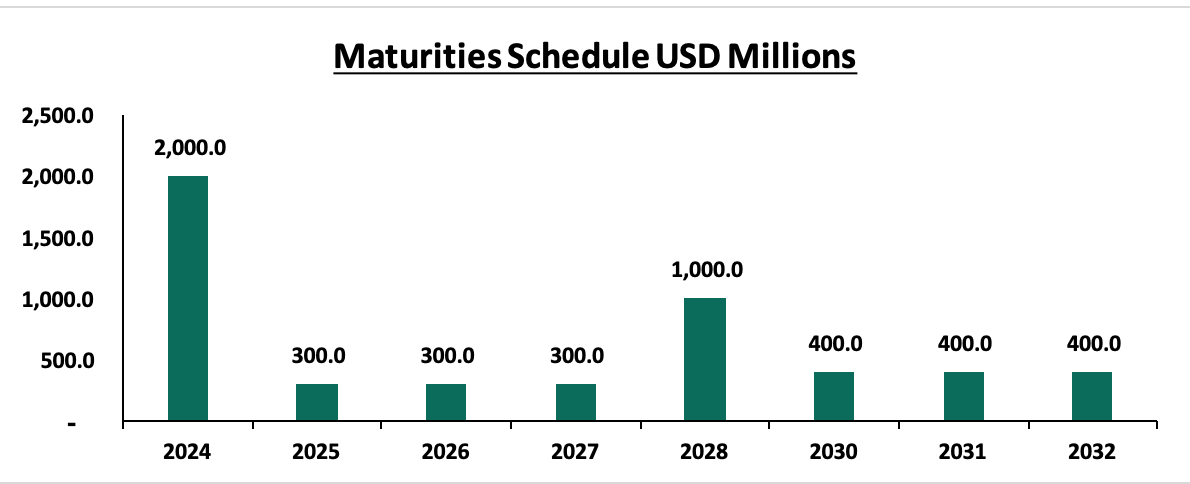

In conclusion, the ballooning debt in the country is a point of concern with both the debt to GDP ratio as well as the debt service to revenue ratio having exceeded the recommended threshold. The changing funding patterns which have seen the country take up more commercial loans could also see the debt levels continue to rise as the country continues to issue more debt instruments in order to pay the maturing debt when due. The commercial loans, being more expensive as compared to multilateral and bilateral loans are expected to further elevate the servicing charge. The maturity profile of Kenya’s debt also raises concerns as its relatively short, which raises maturity concentration risk as the country will be in a continuous state of maturing obligations between 2024 and 2028 since:

- The 10-year Eurobond issued in 2014 will be maturing in 2024,

- There will be the yearly repayments of USD 300.0 mn for the 7-year Eurobond issued in 2019 will be maturing in May 2027, whose repayments, are set to start in 2025, and,

- The 10-year Eurobond issued in 2018 will be maturing in 2028.

Below is a chart showing the maturities schedule:

To finance all these repayments, the country might have to float new Eurobonds. With the prospects of the country’s creditworthiness being lowered further, this would mean that the market conditions in which the country will be issuing the debt facilities won’t be relatively favourable and thus investors will definitely demand a premium for the increased risk meaning further expensive debt for the country elevating debt refinancing risk further.

According to the Draft 2019 Budget Review and Outlook Paper, the Government expects the Debt to GDP ratio in the medium term to decline to around 48.6% by FY’2023/24, as highlighted in the chart below. The decline is expected to be mainly driven by enhanced domestic resource mobilization and expenditure rationalization which will significantly reduce wage related pressures and debt accumulation thus creating fiscal space necessary for economic sustainability. Despite the reason behind the proposal by the Treasury to substitute the debt ceiling with an absolute figure of Kshs 9.0 tn being the need to provide clarity in terms of controls and real-time oversight mechanism on the growth of public debt, we believe it creates more opacity as it is not clear the time horizon in which the country is expected to hit the Kshs 9.0 tn figure. We are of the view that the Treasury should provide more clarity as to that effect in order to address the concerns of possible rapid debt accumulation.

Source: Draft 2019 Budget Review and Outlook Paper

Factoring the current debt levels and the risks abound in the medium term, we are of the view that in order to reduce our debt levels, in line with the IMF sustainable levels, the government should consider achieving:

- Enhanced tax revenue collection growth,

- Involve the private sector in development through Public-Private Partnerships (PPP’s),

- Continue with the fiscal consolidation efforts aimed at reducing recurrent expenditure and improve on development budget absorption rates,

- Enhancing the capacity of the Public Debt Management Office and ensure the implementation of the Medium Term Debt Management Strategies as outlined every financial year, and

- Ensure an enabling environment that promotes Macro-economic stability as it is a critical component for debt sustainability