Jun 24, 2018

The first 5 months of 2018 have been characterized by 5 Eurobond issuances by Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) economies (Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, Ghana and South Africa), jointly raising USD 10.7 bn, with two more countries (Tanzania and Angola) having announced plans to raise foreign public debt through the same avenue this year. Last year, USD 18.0 bn was raised in foreign public debt by economies in Africa, and in the last 5 years, Kenya has had two separate issuances, in 2014 and 2018. Other SSA countries like Ghana and Nigeria have also had two issuances in the last 5 years, with countries like Tanzania looking to make their debut in this space this year.

With the seemingly rising preference for SSA economies to raise long-term foreign public debt through the issue of Eurobonds, this week, we cover SSA as an attractive investment destination and the SSA Eurobonds issued in the last 5 years. For the 2018 Eurobonds, we look at their performance, amounts collected, use of the proceeds and the issuer country’s public debt levels. We also highlight the expected SSA Eurobond issues for the remaining part of the year and the effects on development and debt sustainability for the SSA Region as a result.

Section I: Sub-Saharan African (SSA) as an attractive investment destination

Sub-Saharan African (SSA) has positioned itself as an attractive investment destination as seen by the improving macroeconomic conditions, according to the recently released Regional Economic Outlook report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) dated April 2018, that stated:

- GDP growth in SSA is projected to come in at 3.4% in 2018, up from 2.8% in 2017, supported by (a) higher commodity prices, and (b) improved capital markets access,

- The average current account deficit in SSA is estimated to have narrowed to 2.6% of GDP in 2017 from 4.1% in 2016 driven by better terms of trade and improved policy frameworks during the period. The current account deficit is however, projected to widen slightly to 2.9% in 2018, and,

- Regional annual inflation in SSA fell to just over 10.0% in 2017 from 12.5% in 2016, and is expected to fall further in 2018, driven by declining food prices due to improved weather conditions.

With better macroeconomic conditions, improving political stability, and attractively priced fixed income instruments relative to developed countries - for instance, the 10-year US Treasury bond is currently yielding 2.9%, while the Kenya 2018 10-year Eurobond is currently trading at a yield of 7.0% - the attractive risk adjusted return on SSA fixed income instruments have made SSA securities to become quite popular among global fixed income fund managers.

Having said this, we now look at how SSA has leveraged on its attractiveness through the issuance of Eurobonds to raise foreign public debt.

Section II: Eurobonds as a source of foreign public debt for SSA economies

A Eurobond is a special type of bond that is issued in a currency other than the issuer-country’s home currency. Since it is issued in a foreign currency and its target investors are foreigners, it is considered one way that a country can raise foreign pubic debt.

The first 5 months of 2018 were characterized by Eurobond issuance by 5 Sub Saharan African countries (Kenya: USD 2.0 bn, Nigeria: USD 2.5 bn, Senegal: USD 2.2 bn, Ghana: USD 2.0 bn and South Africa: USD 2.0 bn) and 6 in Africa as a whole (Kenya: USD 2.0 bn, Nigeria: USD 2.5 bn, Senegal: USD 2.2 bn, Ghana: USD 2.0 bn, South Africa: USD 2.0 bn and Egypt: USD 4.0 bn), raising a total USD 14.7 bn, compared to USD 18.0 bn raised in the whole of 2017. From this, it seems that most African economies are opting for Eurobonds as a preferred form of raising external debt, as opposed to pursuing commercial and syndicated debt from international financial institutions, with Eurobonds share of total public debt rising to 19.0% in 2016 from 9.0% in 2007 according to the World Bank African Pulse April 2018 issue. Some of the reasons why this has become a popular source of borrowing of late are as follows:

- Eurobonds appear to be cheaper than commercial loans, with Kenya having borrowed an 8-year USD 750 mn commercial loan at a floating rate of 6.7% above the 6-month London Interbank Offer Rate (Libor) (at 0.6% at the time), hence 7.3% p.a. at the time in Dec 2017, while the longer dated 10-year Eurobond issued just 2 months later was issued at the same rate, and,

- Eurobonds have gained importance as the rates eventually offered are used as benchmarks for pricing of foreign denominated debt instruments by corporates in the issuer country.

SSA countries foreign borrowing appetite has been on the rise, as debt increasingly becomes a critical source of finance for development expenditure. Since the beginning of 2018, 6 countries in Africa have issued Eurobonds, namely: Senegal, Egypt, Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa and Kenya. Out of these, 5 are part of SSA, with the total value raised coming to USD 10.7 bn. Egypt raised USD 4.0 bn through the issue of 5, 10 and 30-year Eurobonds. Of concern however, is that most of the funds raised from the Eurobond issuances are to be used to redeem nearly maturing foreign-denominated debt that was not necessarily more expensive in all cases, and finance national budgets with no clear indication as to whether the funds are to be channelled towards recurrent or development expenditure in all cases, with the latter being the preferred scenario.

While Eurobonds may appear cheaper relative to commercial external debt and good for development expenditure, they still add to a country’s foreign debt burden, and foreign debt exposes economies to the following risks:

- Exchange rate risk: Eurobonds are issued in currencies other than the home currency of the issuer yet a large share of their revenues are in local currency, and hence carry exchange rate risk at the point of interest and principal payments. In the event of depreciation of the local currency with respect to the currency the debt is denominated in, the cost of repaying and servicing the bond would become higher,

- Credit risk: Debt sustainability has been a major concern of late, with concerns around whether some SSA governments will be able to pay the interest payments as well as the principal amounts as and when they fall due, as the public debt levels continue burgeoning over the years to average 56.0% of GDP in 2016 from 37.0% in 2013. Data from the World Bank indicates that SSA countries’ debt sustainability risk has increased significantly, with 18 countries at high risk of debt distress as at March 2018 as compared to 8 in 2013. Data from the recently released IMF regional economic outlook report for Sub-Saharan Africa also indicate that public debt continued to rise in 2017, with about 40.0% of low-income developing countries in the region being in debt distress or at a high risk of debt distress, with the median level of public debt exceeding 50.0% of GDP. Repayment concerns have also been driven by:

- The low levels of economic diversification in SSA, as most countries are commodity driven, which makes them volatile to global price changes and acts of God such as droughts. Notably, growth recovery projections in SSA countries has mainly been tied to increasing international prices of commodities such as oil, and improving weather conditions. Governments need to come up with diversification agendas to make the countries less vulnerable to global economy shocks,

- The fact that most of the proceeds from the issues are diverted to refinancing other debt facilities, as well as investments in non- income generating social infrastructure, and,

- Corruption, which continues to be a major issue as some of the funds raised don’t get to accomplish their intended purpose, with Africa having been ranked the worst in corruption with an average score of 32 out of 100 in the Transparency Corruption Perception Index 2017 report by Transparency International.

- Interest risk: with the recent hike in the Federal Funds rate to a band of 1.75% - 2.00% and the expectation of another 2 hikes in the course of the year, it is expected that yields of SSA Eurobonds will have to also increase to remain more attractive to investors. If this does not happen, it is likely that we will see capital outflows from the region as investors turn their attention to the US, which is considered a less risky investment destination as compared to SSA. This may be detrimental to the region as foreign direct investments have been a key driver of economic growth in the region.

- Susceptibility to shocks from external market conditions: with many countries becoming more reliant to external financing, they also become susceptible from all kinds of shocks coming from external market conditions which can include anything from freezing of markets, new legislations and sudden change of market sentiments.

In the last 5 years:

The last 5 years Eurobonds have become increasingly popular as a form of foreign public debt by SSA countries as evidenced by:

- The value of foreign debt raised by SSA countries through the issuance of Eurobonds has increased by 3.5x to USD 18.0 bn in 2017 from about USD 4.0 bn in 2013, with the increasing need for these economies to fund their development efforts. Seychelles was the first SSA country after South Africa to issue a Eurobond in 2006, after which countries like Ghana, Gabon, Senegal, Nigeria, Namibia, Côte d’Ivoire, Zambia, Rwanda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Angola and Cameroon have proceeded to raise debt through foreign capital markets in a similar manner,

- Amounts raised in single issues have gotten bolder over the years, increasing by 300.0% to USD 2.0 bn on average from USD 500.0 mn on average 10 years back, and,

- SSA countries have also returned to the foreign capital markets for more than one Eurobond issuances with countries having had 2 issuances on average in the last 5 years.

Recently:

Moving on to recent times, 2018 has been quite an eventful year so far in terms of Eurobonds in SSA. The following SSA economies have issued Eurobonds in the last 5 months, with the exception of South Africa (we shall not discuss South Africa in detail as it is not part of our macroeconomic universe of coverage)

- Kenya

In mid-February 2018, officials from the Treasury carried out a road show in the UK and USA to market the country’s second Eurobond issue. On 23rd February 2018, the Government of Kenya issued its second set of Eurobonds, a 10-year and 30-year Eurobond at coupons of 7.3% and 8.3%, both 30 bps below 7.6% and 8.6%, respectively, which had been advised by the banks working on the deal. The Eurobonds are listed on the London and Irish Stock Exchanges. The proceeds were to be disbursed towards development expenditure and debt liability management. The issue was 7.0x oversubscribed with bids received at USD 14.0 bn as compared to the USD 2.0 bn target, despite (i) Moody’s downgrade of the government’s issuer rating to “B2” from “B1” previously, which the government refuted, claiming that their research was not well informed, and (ii) the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF’s) decision to withdraw their stand-by credit facility effective March 2018 at the time, citing the government’s failure to lower its budget deficit to 3.7% of GDP by 2018/19. These two events took place just before the issue date. Key to note is that the IMF has since agreed to extend the facility by 6 months to allow for completion of reviews.

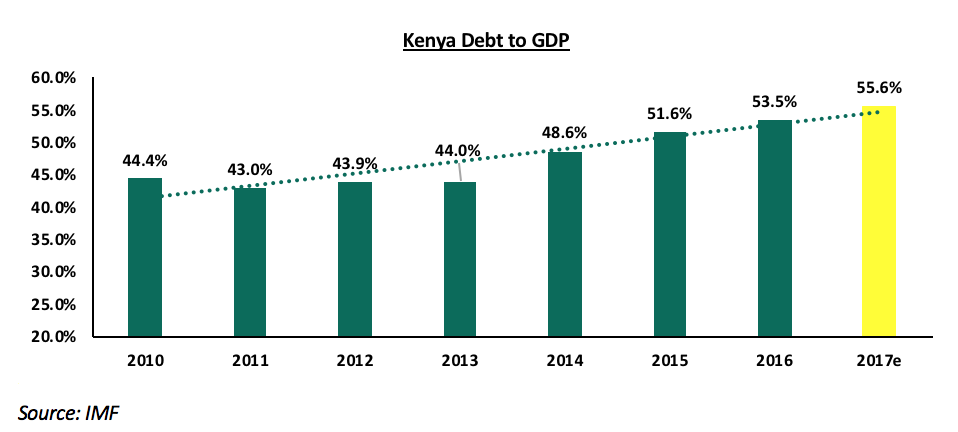

Kenya’s public debt to GDP is estimated to have hit 55.6% by the end of 2017, 5.6% above the East African Community (EAC) Monetary Union Protocol, the World Bank Country Policy and Institutional Assessment Index, and the IMF threshold of 50.0%. This is a rise from 43.9% 5-years ago, and 38.4% 10-years ago. It is estimated that Kenya will use approximately 40.3% of our revenue raised from tax collection to finance debt payments in the fiscal year 2017/18. After the 2018 Eurobond issue, the country’s public debt to GDP ratio could soar above 60.0%, according to Moody’s, unless proper policies are put in place to control this by the government. As detailed in our topical on Kenya’s Public Debt, Should We Be Concerned?, the government has already embarked on measures to improve debt management, also detailed in the 2018 Budget Policy Statement (BPS). Now with Kenya in the limelight with regards to public debt levels, we expect that implementation of these debt management strategies will be better than it has been in previous years.

The chart below shows Kenya’s debt-to-GDP ratio over the last 7 years:

- Nigeria

On 23rd February 2018, Nigeria managed to raise USD 2.5 bn through the issue of a 12 and 20-year Eurobond at yields of 7.1% and 7.7%, respectively. The issue was 4.6x oversubscribed with the bids received at USD 11.5 bn against the target of USD 2.5 bn. This was despite a downgrade, by the Moody's Investors Service, of Nigeria's long-term issuer and senior unsecured debt rating to “B2” from “B1”, with the rating outlook remaining “stable”. However, with prospects of a recovering economy following the improvement in oil prices and production, as well as continued strengthening of its agricultural sector, investors seem to have a positive outlook for Nigeria’s economy going forward. The proceeds from the Eurobond will go towards redeeming expensive Naira debt, and in funding infrastructure development so as to spur economic growth.

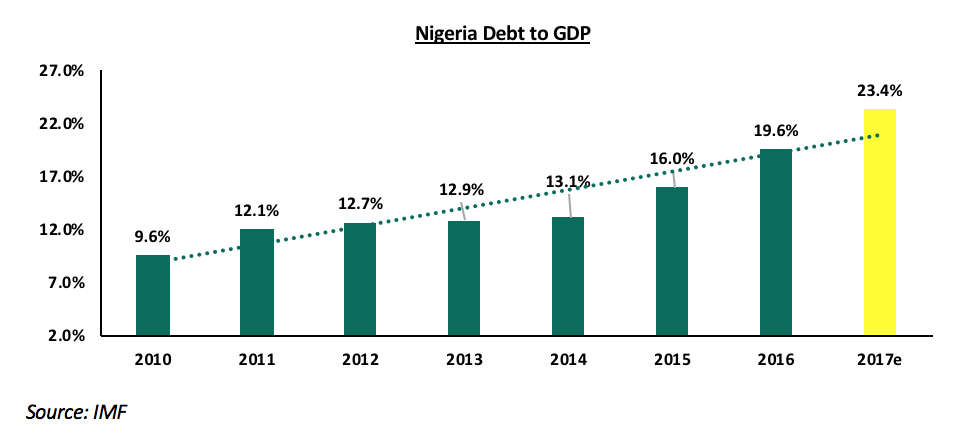

As at December 2017, Nigeria's public debt stock stood at USD 71.0 bn, an increase of 23.7% from USD 57.4 bn in December 2016. The public gross debt to GDP ratio in 2017 stood at an estimated 23.4%, an increase from 19.6% in 2016, well below the IMF recommended threshold of 50.0%. The move to use part of the proceeds to refinance the more expensive local debt will reduce debt-financing costs as well as reduce the roll-over risks from the short-tenured domestic debt. Nigeria’s government funds its budget mostly through proceeds from oil exports, and hence, we believe the increase in debt in 2017 was to plug in lower oil sector proceeds given the reduction in production and global oil prices in previous years. Now with recovery in both and efforts to diversify the economy, we expect debt levels to once again reduce going forward.

The chart below shows Nigeria’s debt-to-GDP ratio over the last 7 years:

- Senegal

In March 2018, Senegal issued two Eurobonds, a 10-year and 30-year, at coupons of 4.8% and 6.8%, 2.5% points and 1.5% points lower than Kenya’s February 2018 issue with similar tenures, respectively. The issue was 4.5x subscribed with bids received worth USD 10.0 bn, against a target of USD 2.2 bn. The lower than recommended yields, the oversubscription, and Moody’s upgrade of the country’s long-term issuer and senior unsecured debt ratings to “Ba3” from “B1”, and changing of the outlook to “stable” from “positive” are indications of the growing foreign demand for higher yielding emerging and frontier market bonds. We believe that Senegal managed to issue its Eurobonds at lower yields than similar tenure issues in the continent owing to:

- Recent offshore oil & gas discoveries have enabled the country to attract increased foreign direct investment,

- Senegal enjoys strong political stability with no sign of any upheaval in the future as well, unlike other issuer countries like Kenya, Nigeria, Egypt and South Africa, and

- Robust economic growth, with Senegal’s 2017 GDP growth estimated at 6.8% and the economy being projected to grow by 7.0% in 2018, one of the fastest growing economies in SSA.

The government aims to use USD 200.0 mn from the net proceeds to buy back some of its dollar-denominated debt with a maturity date of 2021. The remainder is to be channelled to infrastructure projects, and repay in full the outstanding amounts of the 2018 Bridge, African export-import bank (Afreximbank) and Credit Suisse loans worth EUR 250.0 mn, EUR 137.5 mn and EUR 112.5 mn, respectively.

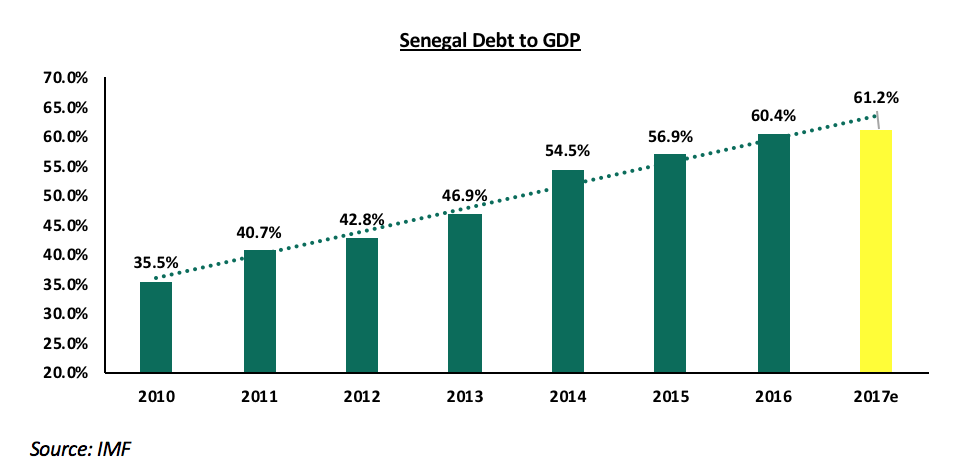

According to the IMF’s Senegal Debt Sustainability Analysis, public debt for Senegal was estimated at 61.2% of GDP at the end of 2017, an increase from 60.4% in 2016, and above the 50.0% IMF threshold. Despite this, the move to refinance some of their debt with cheaper funds is a commendable debt management strategy. In addition, some of the proceeds are going to be channelled towards infrastructure projects that will further boost GDP growth and reduce the debt to GDP ratio below the recommended thresholds, going forward.

The chart below shows Senegal’s debt-to-GDP ratio over the last 7 years:

- Ghana

Ghana raised USD 2.0 bn through the issue of a 10-year and 30-year Eurobond in May 2018, at rates of 7.6% and 8.6%, respectively, both 30 bps below what Kenya managed to issue at. The issue was 4.0x oversubscribed with bids received coming in at USD 8.0 bn, against USD 2.0 bn on offer. This came after Moody’s Investor Service affirmed Ghana’s long-term issuer and senior unsecured bond rating at “B3” with a “stable” outlook. The rating was affirmed due to Ghana’s efforts towards debt restructuring, despite their debt levels still being high; while the stable outlook reflected the country’s strong GDP growth and positive outlook for 2018, with economic growth prospects at 8.5%. This is the first time the West-Africa state is issuing a 30-year Eurobond as it seeks to lengthen its foreign debt tenure. The government plans to use the proceeds for debt management and budgetary support.

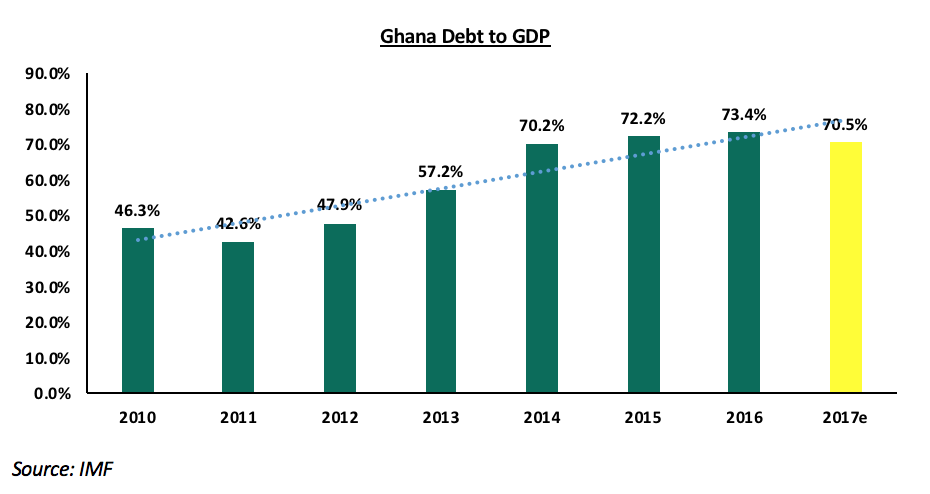

Data from the IMF estimates that Ghana’s debt-to-GDP ratio hit 70.5%, 20.5% points above the IMF threshold of 50.0%, though this was a slight reduction from 73.4% in 2016. As mentioned in our focus note titled Kenya’s Public Debt, Should We Be Concerned?, the IMF stepped in to bail out Ghana’s lenders in April 2015 through concessional loans, and by introducing reforms that had to be adopted by the government such as reduction of government expenditure and increases in tax rates to boost revenue collected and reduce the budget deficit. This was after Ghana’s risk of debt crisis was at its peak, stemming from a gradual but steady rise in public borrowing on the back of oil discovery and rising global commodity prices, as Ghana is commodity-dependent, big on cocoa and gold exports; which started going sour in 2013 when commodity prices plummeted. With these measures in place, the budget deficit is expected to reduce to about 4.5% of GDP by 2018, from 6.5% as per their 2018 Budget Statement, effectively reducing annual borrowing and the government debt-to-GDP ratio below the 50.0% threshold. The IMF is however still ongoing. With the new government working towards these measures in place and the IMF programme still ongoing, we expect that Ghana will use the proceeds to retire expensive debt and support development expenditure, to enhance increased tax collection, which will in future support the budget and reduce their borrowing requirements.

The chart below shows Ghana’s debt-to-GDP ratio over the last 7 years:

Section III: Summary and Conclusion

Section III: Summary and Conclusion

Below is a table showing a summary of currently outstanding SSA Eurobonds:

|

Country |

Issue Tenor (yrs) |

Issue Date |

Maturity Date |

Effective Tenor (yrs) |

Coupon |

Current Market Yield |

Coupon to Current Yield |

|

Ghana |

31 |

5/16/2018 |

6/16/2049 |

31.0 |

8.6% |

8.8% |

0.1% |

|

S.Africa |

30 |

5/22/2018 |

6/22/2048 |

30.0 |

6.3% |

6.4% |

0.1% |

|

Egypt |

30 |

4/29/2010 |

4/30/2040 |

21.9 |

6.9% |

7.0% |

0.1% |

|

Senegal |

30 |

3/13/2018 |

3/13/2048 |

29.7 |

6.8% |

7.8% |

1.1% |

|

Morocco |

30 |

12/11/2012 |

12/11/2042 |

24.5 |

5.5% |

4.9% |

(0.6%) |

|

South Africa |

30 |

9/27/2017 |

9/27/2047 |

29.3 |

5.7% |

5.7% |

0.1% |

|

Nigeria |

30 |

11/28/2017 |

11/28/2047 |

29.5 |

7.6% |

8.2% |

0.6% |

|

Kenya |

30 |

2/28/2018 |

2/28/2048 |

29.7 |

8.3% |

8.7% |

0.4% |

|

Nigeria |

20 |

2/23/2018 |

2/23/2038 |

19.7 |

7.7% |

8.1% |

0.4% |

|

Senegal |

16 |

5/23/2017 |

5/23/2033 |

14.9 |

6.3% |

7.3% |

1.1% |

|

Ghana |

15 |

10/14/2015 |

10/14/2030 |

12.3 |

10.8% |

7.9% |

(2.8%) |

|

Zambia |

12 |

7/30/2015 |

7/30/2027 |

9.1 |

9.0% |

10.6% |

1.6% |

|

Nigeria |

12 |

2/23/2018 |

2/23/2030 |

11.7 |

7.1% |

7.6% |

0.5% |

|

Ghana |

11 |

9/18/2014 |

1/18/2026 |

7.6 |

8.1% |

7.6% |

(0.6%) |

|

Ghana |

11 |

5/16/2018 |

5/16/2029 |

10.9 |

7.6% |

7.9% |

0.3% |

|

Senegal |

10 |

3/13/2018 |

3/13/2028 |

9.7 |

4.8% |

5.4% |

0.7% |

|

Senegal |

10 |

7/30/2014 |

7/30/2024 |

6.1 |

6.3% |

6.5% |

0.3% |

|

Kenya |

10 |

6/24/2014 |

6/24/2024 |

6.0 |

6.9% |

6.8% |

(0.0%) |

|

Zambia |

10 |

4/14/2014 |

4/14/2024 |

5.8 |

8.5% |

10.7% |

2.2% |

|

Senegal |

10 |

5/13/2011 |

5/13/2021 |

2.9 |

8.8% |

5.6% |

(3.1%) |

|

Zambia |

10 |

9/20/2012 |

9/20/2022 |

4.2 |

5.4% |

9.6% |

4.2% |

|

Kenya |

10 |

2/28/2018 |

2/28/2028 |

9.7 |

7.3% |

7.6% |

0.3% |

|

Ghana |

10 |

7/8/2013 |

7/8/2023 |

5.0 |

7.9% |

7.2% |

(0.7%) |

|

Ghana |

6 |

9/15/2016 |

9/15/2022 |

4.2 |

9.3% |

5.5% |

(3.8%) |

|

Nigeria |

5 |

7/12/2013 |

7/12/2018 |

0.1 |

5.1% |

5.7% |

0.6% |

|

Kenya |

5 |

6/24/2014 |

6/24/2019 |

1.0 |

5.9% |

6.8% |

1.0% |

Key to note from the table:

- Senegal managed to issue its Eurobond at lower rates compared to other issues at 4.8% for the 10-year and 6.8% for the 30-year bond. This is due to the country’s stable political outlook and also the fast economic growth driven by the discovery of the 15.0 tn cubic feet of natural gas and 1.5 bn barrels of crude oil in 2016, which add to the positive growth prospects of the country, and

- The yields on most of the Eurobonds have been on the rise since issue, due to a higher risk pricing by investors that has seen flight of capital back to the US markets, attributed to the rising interest rates from the 2 Fed rate hikes experienced during the year, which has seen investors demanding a premium on debt from emerging and frontier market due to the risk associated with them.

In conclusion, SSA Eurobonds have proven to be an attractive investment offering with relatively higher yields than in the developed markets. With a positive outlook on economic growth - SSA growth is projected to rise to 3.4% in 2018 from 2.8% in 2017 - as well as improved political stability in the region, the SSA region is expected to remain an attractive investment destination for investors looking for emerging & frontier market exposure. This being said, exchange rate risk and debt sustainability remain key points of concern, as most of the proceeds are being used to refinance other debt facilities and to finance non-income generating social investments such as healthcare and education. The low levels of diversification of the economies and over reliance on commodities and agriculture make the region volatile to global price changes and weather conditions. Nonetheless, the issue of Eurobonds in the SSA region has become an important source of government funding and has enhanced economic growth.

More countries in SSA are planning to issue Eurobonds this year, though the conditions are expected to be tougher, with the Fed being expected to further hike the federal funds rate two more times this year, with 2 hikes already having taken place with the recent one in June 2018, when rates were increased to a band of 1.50% - 1.75% from 1.25%- 1.50%, previously. These countries include:

- Angola is expected to issue a Eurobond to raise USD 2.0 bn, to finance public investment projects while

- Tanzania is also expected to debut its first Eurobond worth USD 700.0 mn to finance infrastructure projects after receiving its first-time local and foreign currency issuer rating of “B1” from Moody’s, with a “negative” outlook due to an increasingly unpredictable policy environment weighing on the business climate.

If all these take place, this should bring the total external borrowing through Eurobonds in SSA during the year to an estimated USD 13.4 bn. Increased concerns around debt sustainability in SSA may arise from this, but taking on the debt might be beneficial should the borrowed funds be channelled towards (i) refinancing more expensive foreign currency denominated debt and to lengthen tenures, and not simply to repay maturing debt obligations, and (ii) development expenditure on projects that will in turn boost economic growth in these countries.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the writers where particulars are not warranted. This publication, which is in compliance with Section 2 of the Capital Markets Authority Act Cap 485A, is meant for general information only and is not a warranty, representation, advice or solicitation of any nature. Readers are advised in all circumstances to seek the advice of a registered investment advisor.