May 13, 2018

We revisit the interest rate cap following the recent announcement by the Treasury that they were in the process of completing a draft proposal that will address credit management in the economy. Treasury Cabinet Secretary, Henry Rotich, stated that the draft law would not only be centered on the cost of credit, but will also present some consumer protection policies. “The package of reforms is expected to address the real cause of the high credit cost in Kenya, and eventually lead to the elimination of the law capping interest rates,” said Henry Rotich during the launch of the 2018 Economic Survey Report in Nairobi. A repeal of the law was one of the promises made to the IMF, for the extension of the USD 1.5 bn stand-by credit and precautionary facility. The IMF said in a statement, “On March 12, the executive board of the IMF approved Kenyan authorities’ request for a 6-month extension of the country’s stand-by arrangement to allow additional time to complete outstanding reviews”. The availability of the credit facility was tied to the Treasury’s fulfillment of the promise it made to cut back on the fiscal deficit through a raft of budget consolidation measures, including cutbacks on public spending, together with a repeal of the interest rate cap law. We therefore revisit the issue of the interest rate cap, focusing on;

- Background of the Interest Rate Cap Legislation - What Led to Its Enactment?

- A Review of the Effects It Has Had So Far In Kenya

- Case Studies of Other Interest Rate Cap Regimes in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Our Views on the Way Forward - including our view of what should be included as part of the amendment or elimination of the law, with an emphasis on stimulating capital market alternatives.

Section I: Background of the Interest Rate Cap Legislation - What Led to Its Enactment?

The enactment of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, that capped lending rates at 4.0% above the Central Bank Rate (CBR), and deposit rates at 70.0% of the CBR, came against a backdrop of low trust in the Kenyan banking sector about credit pricing due to various reasons;

- First, the period was marred with several failures of banks such as Chase Bank Limited, Imperial Bank Limited and Dubai Bank, due to isolated corporate governance lapses. The failure of these banks rendered depositors helpless and unable to access their deposits in these banks. The fact that no single prosecution was ongoing at the time, for alleged malpractices that led to the collapse of some of the banks such as Imperial Bank, only served to infuriate depositors who had their deposits locked in these institutions,

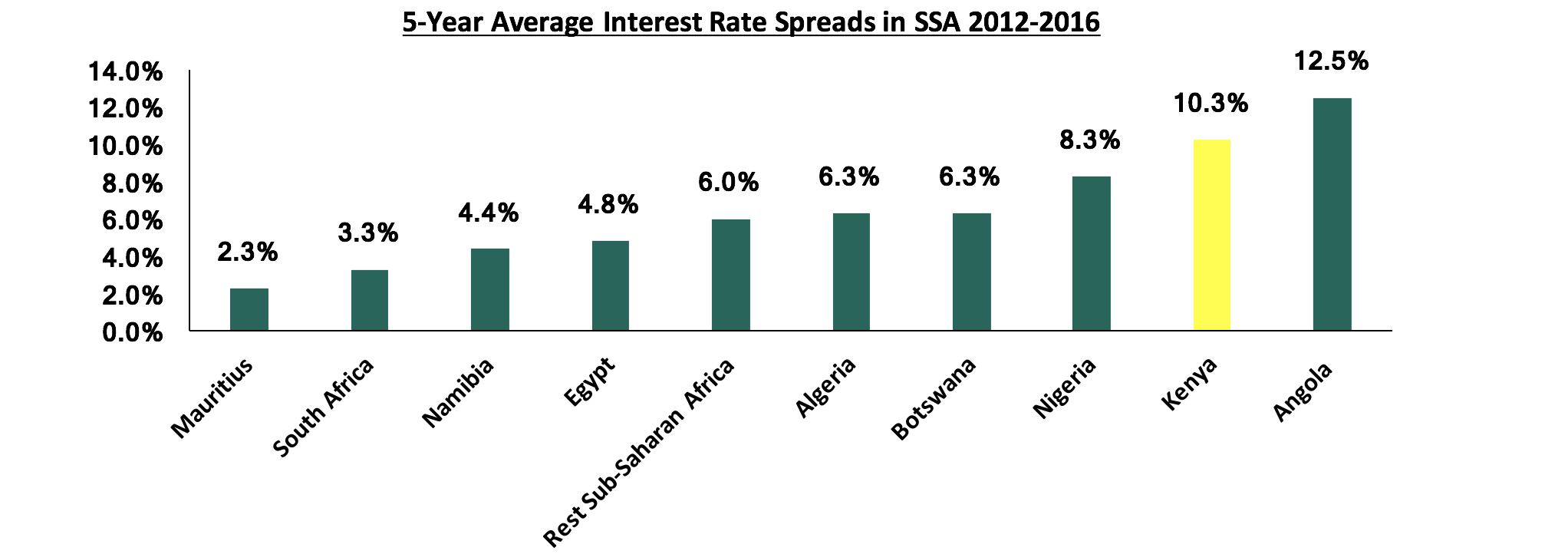

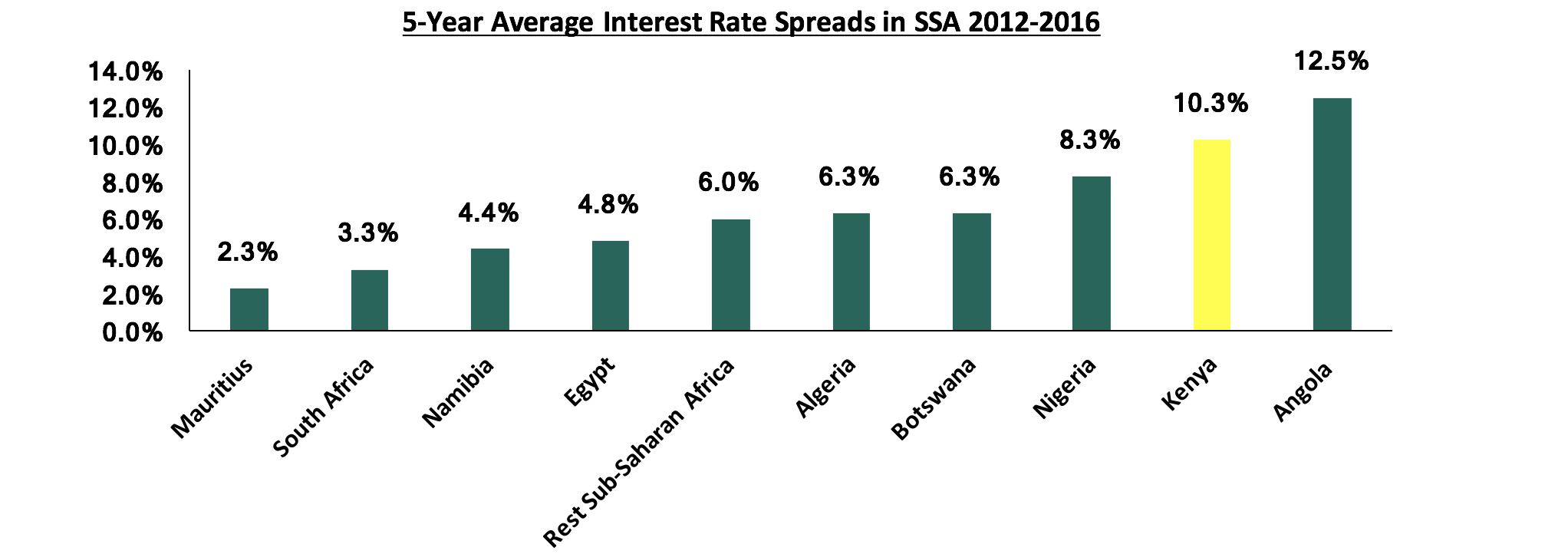

- The cost of credit was high at approximately 21.0% per annum, yet on the other hand, the interest earned on deposits placed in banks was low, at approximately 5.0% per annum. This led to a high spread between the lending rates and deposit rates as shown in the graph below,

- Credit accessibility was also subdued under this regime of expensive debt, as a lot of individuals opted out of seeking debt from commercial banks, owing to the opacity involved in the loan terms. Thus most individuals and entities opted for alternative sources of funding such as “soft loans” other than from banks, and,

- Banks are the primary source of business funding in the country, providing 95.0% of funding, with other alternative sources such as the capital markets providing a combined 5.0%, compared to developed markets where banks provide only 40.0% of the credit in the economy. This skewed source of funding in Kenya was in favor of the banks, as they would price loans on their terms, as opposed to the optimal market rate. This low level of competition from alternative sources of funding in part contributed to high interest rate charges levied by banks.

This fueled anger from the Kenyan public, who accused banks of unfair practice in the quest for extremely high profits at the expense of the borrowers and savers. As a result, banks in Kenya had been making one of the highest profits in the region, as shown in the charts below for the period between 2012 and 2016:

Source: World Bank

Source: IMF

This culminated in the interest rate cap bill being tabled in parliament, and due to its populist nature was passed and signed into law by the President on August 24th, 2016, and it was enforced from September 14th 2016.

Our view has always been that the interest rate cap regime would have adverse effect on the economy, and by extension, to the Kenyan People. We have previously written about this in five focus notes, namely:

- Interest Rate Cap is Kenya’s Brexit - Popular But Unwise, dated 21st August 2016, three days before the signing into law of the interest rate cap, where we first expressed our view that the interest rate cap would have a clear negative impact on the economy. We noted that free markets tend to be strongly correlated with stronger economic growth, plus we noted the lack of compelling evidence of any economy where interest rate capping was successful, as evidenced by the World Bank report on the capping of interest rates in 76 countries around the world. In Zambia, for example, interest rate caps were introduced in December 2012 and repealed 3-years later, in November 2015, after the impact was found to be detrimental to the economy. We called for the implementation of a strong consumer protection agency and framework, coupled with the promotion of initiatives for competing alternative products and channels,

- Impact of the Interest Rate Cap, dated 28th August 2016, four days after the interest rate cap bill was signed into law, where we highlighted the immediate effects of the interest rate cap, as banking stocks lost 15.6% in 2-days. Here, we re-iterated our stance on the negative effects of the interest rate cap, while identifying the winners and losers of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015,

- The State of Interest Rate Caps, dated 14th May 2017, 9-months after the interest rate cap was signed into law, where we assessed the interest rate cap and its effects on private sector credit growth, the banking sector and the economy in general, following concerns raised by the IMF. We noted that the law had the effect of (i) inhibiting access to credit by SMEs and other “small borrowers” whom banks cited as being unable to fit within the 4.0% risk premium, and (ii) contributed to subduing of private sector credit growth, which was recorded at 4.0% in March 2017. We suggested that policymakers review the legislation, highlighting that there existed, and continues to exist, opportunities for structured financial products and private equity players to come in and provide capital for SMEs and other businesses to grow, and consequently improve private sector credit growth,

- Update on Effect on Interest Rate Caps on Credit Growth and Cost of Credit, dated 23rd July 2017, approximately 1-year after the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015 was signed into law, where we analyzed the decline in private sector credit growth and lending by commercial banks, coupled with the elevated total cost of credit, which was higher than the legislated 14.0%, as banks loaded excessive additional charges, while noting that the large banks, which control a substantial amount of the banking sector loan portfolio, were the most expensive. We suggested (i) a repeal or modification of the interest rate cap, (ii) increased transparency, (iii) improved and more accommodating regulation, (iv) consumer education, and (v) diversification of funding sources into alternatives, and,

- The Total Cost of Credit Post Rate Cap, dated 14th January 2018, where we analyzed the true cost of credit, initiatives put in place to make credit cheaper and more accessible, the impact of the interest rate cap on private sector credit growth, and what more can be done do remedy the effects of the interest rate cap.

Having now been in effect for 21-months, plans to review the law have been gaining traction because there is significant evidence that its intended objectives have not been achieved. On the campaign for review are banks, private sector players, organizations such as the IMF, and the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK). The CBK has mentioned that according to its research, the interest rate cap has failed to achieve the objectives it was drafted for, mainly access to credit at favorable pricing. Instead, the cap has (i) inhibited the growth of private sector credit in the economy, and (ii) made it difficult for the enforcement of monetary policy action, as any action on the benchmark CBR would trickle down to credit pricing. The IMF has also been vocal in its recommendation of a repeal of the law. The IMF noted that the rate cap had the effect of locking out a lot of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) from accessing credit, and with SMEs being the largest proportion of the private sector, this translated to reduced economic output. A repeal of the law was also part of the commitments made by the National Treasury when seeking an extension to use the USD 1.5 bn credit and precautionary facility by the IMF. The facility is normally used in case of any economic shocks that may affect the economy. The Cabinet Secretary thus indicated that a draft proposal that will address credit management in the economy would be tabled in parliament in June this year.

On the flip side, some organizations have come out in support of the interest rate cap, namely the Institute of Certified Public Accountants of Kenya (ICPAK). The organization has raised concerns that a repeal of the interest rate cap would lead to a return to the previous regime characterized by exorbitant borrowing costs. They argue that although the concerns raised are genuine, it is still too early to assess the impact of the rate cap to the economy, and that the challenges experienced are not directly attributable to the rate cap. ICPAK together with the Consumer Federation of Kenya (CoFEK), are of the view that we need to address the challenges that led to the enactment of rate cap, mainly the high cost of borrowing, and ensure that there is a better balance between the interests of the market players and those of the consumers.

Section II: A Review of the Effects It Has Had So Far In Kenya

The interest rate cap has had the following four key effects to Kenya’s economy since its enactment:

- Private Sector Credit Growth Dropped Dramatically

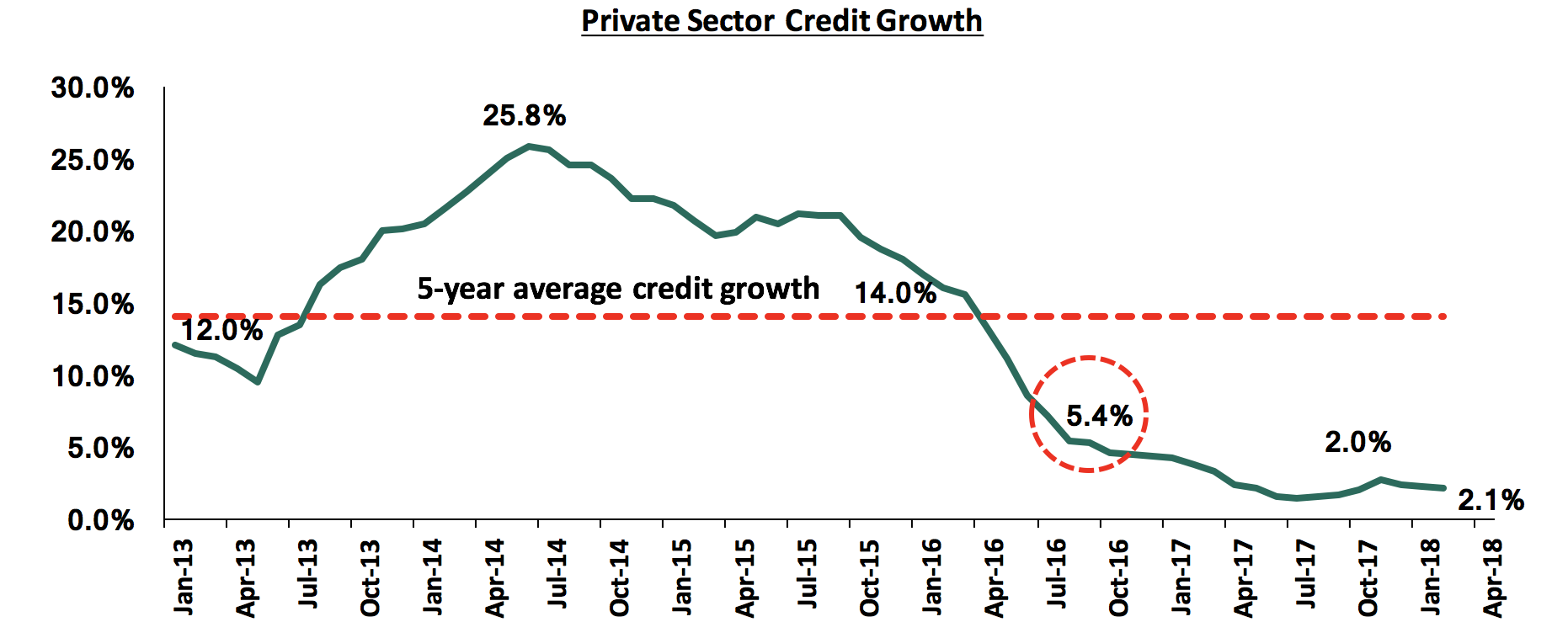

Private sector credit growth in Kenya has been declining, and the enactment of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, had the adverse effect of further subduing credit growth. The law capped lending rates at 4.0% points above the CBR. This made it difficult for banks to price some of the borrowers within the set margins, a majority being SMEs, as they were perceived “risky borrowers”. Banks thus invested in asset classes with higher returns on a risk-adjusted basis, such as government securities. As can be seen from the graph below, private sector credit growth touched a high of 25.8% in June 2014, and has averaged 14.0% over the last five-years, but has dropped to 2.0% levels after the capping of interest rates.

According to the September 2016 CBK Credit Officer Survey, banks tightened their credit standards immediately after the interest rate cap was enforced in Q4’2016. The sectors mainly affected were Agriculture, Financial Services, Energy, Trade, Transport, Personal/ Household and Manufacturing. Tighter credit standards have persisted, and private sector credit has not accelerated since the cap was effected, coming in at 2.1% in March 2018. The resultant effect is that the legislation has not achieved its primary objective of improving credit growth to the private sector.

- Loan Accessibility Reduced

Immediately after the enactment of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, banks saw an increase in demand for loans, as the number of loan applications increased by 20.0% in Q4’2016 according to the CBK Credit Officer Survey of October-December 2016. This was due to borrowers attempting to get access to cheaper credit. However, this demand was not matched with supply of loans by banks as evidenced by:

- Decline in the number of loan accounts: The number of loan accounts in large banks (Tier I) declined by 27.8%, the largest among the three tiers, followed by Tier II banks with a decline of 11.1% between October 2016 and June 2017. Tier III banks however had the number of loan accounts increase by 4.5%. This shows that loan accessibility reduced, with the larger tier banks being the front-runners in reducing lending, especially to small borrowers. Thus, the rate cap law hampered credit accessibility to small scale borrowers in the private sector, another objective of the interest rate cap that was not achieved, and

- Increase in average loan size: The average loan size increased by 36.0% to Kshs 548,000 from Kshs 402,000 between October 2016 and June 2017. This points to lower credit access by smaller borrowers, while also demonstrating that credit was extended to larger and more “secure” borrowers. The increase in the average loan size was highest for the Tourism and Hotels sector, which had the average loan size grow by 76.0%. Building and Construction had the loan size increase by 63.0%. On the other hand, Personal & Household was the only segment that witnessed a decrease in loan size, with the average loan size declining by 24.0%. The CBK noted that banks of different tiers recorded different increments in loan size, with Tier I banks recording a 42.0% increase in loan size to Kshs 396,000 from Kshs 278,000, followed by Tier III banks at 21.0% to Kshs 2.0 mn from Kshs 1.7 mn, and Tier II banks by 2.0% to Kshs 1.8 mn from Kshs 1.7 mn. The huge increase in average loan size by Tier I banks demonstrates their unwillingness to lend to the small borrowers and SMEs, who are generally riskier borrowers who could not fit the legislated rates.

- Decrease in average loan tenures: The average loan tenure declined by 50.0% to 18-24 months compared to 36-48 months prior to the introduction of the interest rate cap. This is due to bank’s increasing their sensitivity to risk, thereby opting to extend only short-term and secured lending facilities to borrowers, rather than longer-terms loans to be used for investments, according to the latest survey by the Kenya Bankers Association (KBA) on the effects of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015. As per the KBA report, reversing the impact of the rate cap could take up to 12-months, especially to allow the market to start correcting on credit pricing and disbursement, underlining the need for swift action to review the law and repeal the rate cap.

- Bank’s Operating Models Changed to Mitigate Effects of the Rate Cap Legislation

The enactment of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, saw banks changing their business and operating models to compensate for reduced interest income (their major source of income) as a result of the capped interest rates. Furthermore, the enactment of the law saw increased cost of funds, as deposit rates were floored at 70.0% of the CBR, which meant increased interest expense to banks. With the reduction in income (interest income), and increased cost of funds, the banks’ profitability margins were set to reduce. Thus, banks adapted to this tough operating environment by adopting new operating models in several ways:

- Increased focus on Non-Funded Income (NFI): The increased cost of funds from the higher deposit rates coupled with reduced interest income from loans led to banks’ increased focus on NFI. This is evidenced by the fact that the proportion of non-interest income to total income stood at 28.4% in September 2016, and eventually rose to the current 33.6%. Non-interest charges on loans in the form of fees on loans also increased. As such, the entire cost of loans as measured by the Annual Percentage Rate (APR) was still higher than 14.0%, remaining consistent at 16.7%, albeit lower than the average of 21.0% before the enactment of the interest rate cap, but mainly because banks shunned away from risky borrowers. To increase NFI, banks increased “other fees”, e.g. appraisal fees, that was made to mitigate the impacts of reduced income due to the reduced interest rates on loans charged,

- Increased focus on transactional accounts: Banks also increased their focus to growing their transactional accounts as opposed to interest earning accounts. Furthermore, many commercial banks moved to reclassify deposit accounts to limit the number of accounts that qualify to earn the interest set in the amended law. Some banks sent out notices to customers indicating that only fixed accounts qualified to earn interest,

- Increased lending to the government: There was increased lending to government rather than individuals and the private sector, given the higher risk-adjusted returns offered by government debt. Banks increasingly allocated funds to government securities, as opposed to lending, even as the mobilized deposits increased. This is evidenced by the increase in banks’ share of total government debt, that stood at 45.1% in 2015, which increased to 51.5% in 2016 after the enactment of the rate cap law, and is at 55.0% currently, and,

- Cost rationalization: Banks also stepped up their cost rationalization efforts by increasing the use of alternative channels by mainly leveraging on technology such as mobile money and internet banking to improve efficiency and consequently reduce costs associated with the traditional brick and mortar approach. This led to the closure of branches and staff layoffs in a bid to retain the profit margins in the tough operating environment, due to depressed interest income.

Banks’ profitability thus generally reduced after the enactment of the cap, as evidenced by the return on equity and return on assets that declined to 19.8% and 2.3%, compared to the 5-year averages of 29.2% and 4.4%, respectively. The listed banking sector recorded a decline in earnings by 1.0% in 2017, from a growth of 4.4% in 2016. Banks have adjusted their business models to mitigate against the effects of the legislation, rather than reduce credit costs or increase access to credit, which were the initial objectives of the law. The “punishment” that the public wanted meted out to the banks has been mitigated by the sector using the above changes in operating model. We are of the view that any repeal or amendment will also be mitigated by the dynamic banking sector, hence the best approach to addressing banking sector dominance and overreliance in the sector is to stimulate alternative funding sources.

- Weakening of Monetary Policy Effectiveness

The Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, has made it difficult for the Central Bank to conduct its monetary policy function. This is majorly because any alteration to the CBR would directly affect the deposit and lending rates. During the period of enactment of the interest rate cap law, private sector credit was on a declining trend. Inflation was also low and was expected to decline. Therefore, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decided to lower the CBR so as to inject growth stimulus into the economy. This however had the opposite and unintended result as credit growth declined further. Thus, the monetary policy decision failed to yield the expected results of improving credit growth. Expansionary monetary policy thus is difficult to implement since lowering the CBR has the effect of lowering the lending rates and as a consequence, banks find it even more difficult to price for risk at the lower interest rates, leading to pricing out of even more risky borrowers, and hence further reducing access to credit. On the other hand, if the CBK was to employ a contractionary monetary policy, so as to reduce inflation and credit growth for example, then raising the CBR would have the converse effect of increasing the supply of credit in the economy since banks would be able to admit more riskier borrowers. Therefore, the monetary policy function of the Central Bank cannot be effectively executed in a regime with capped interest rates, and especially where the pricing is pegged on the Central Bank Policy rate such as the CBR in this case. This hampers the CBK’s ability to carry out its mandate of ensuring price stability in the economy under a capped interest rate regime.

Having taken the above four effects into consideration, it is clear that the legislation has not achieved its intended effect. The IMF has maintained that with the rate cap in place, lending to Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises has been inhibited, and since they are significant contributors to the country’s output, then GDP growth is negatively affected.

To grant the extension to the precautionary credit facility, IMF set conditions for both fiscal consolidation and modification of interest rate controls. The National Treasury as a result agreed to the conditions set by the IMF and has a 6-months grace period to effect these conditions. The stand-by facility is especially important in the event the economy experiences external shocks that may put upward pressure on the Kenya Shilling.

This leaves the inevitable proposition of a repeal of the rate cap law, just as was the case in Zambia. However, it will be difficult owing to the populist nature of the law, even though it makes economic sense to repeal it. Consideration however has to be made of the challenges that lead to the initial enactment of the law.

Section III: Case Studies of Other Interest Rate Cap Regimes in Sub Saharan Africa

We are not surprised that the interest rate cap regime has not been effective, given the history of such policy action in other countries. We present two quick case studies:

- Zambia

The Central Bank of Zambia introduced a cap on the effective interest rates charged by banks at 9% above the Central Bank Rate in 2012. This led to the Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFI) that mainly included microfinance institutions, leasing finance institutions and building societies, thriving by providing credit to people who were perceived ‘‘risky borrowers’’ and could not be priced within the interest rate cap. Borrowing costs rocketed, with microfinance institutions in the country charging an average effective annual rate of 109.2% on the loans issued. These high costs led to increased public unrest, which culminated with the Central Bank of Zambia introducing another interest rate cap on the effective interest rates charged by Non-Bank Financial Institutions. Thus, the maximum effective annual lending rate for all companies designated as Microfinance institutions was capped at 42% p.a. and all other NBFI had the maximum annual effective lending rate at 30% p.a. The second interest rate cap resulted in a reduction in lending, especially to the middle and low-income group, that initially benefited from access to these loans. Furthermore, access to credit from more established institutions such as commercial banks was also reduced, since most people seeking credit were already highly leveraged and already falling into a debt trap. Thus, they could not be priced within the set margins of commercial banks at 9% of the Central Bank Rate. This had the effect of reducing overall credit to personal and household entities, together with small businesses, leading to reduced economic output. As a result, the Zambian Government repealed the interest rate caps, and replaced the cap with a raft of consumer protection policies in November 2015. The policies focused on reducing the opacity in the pricing of the loans by ensuring full disclosures to the borrowers. The conditions for the repeal stipulated tough sanctions for any institutions defying the set out consumer protection policies. The Central Bank even went a step further and issued a disclosure template that will be issued to the prospective borrower by the issuing institutions, so as to provide full disclosure and more clarity on the borrowing terms. This has aided in reducing the overall cost of borrowing from the high average of 109.2% p.a. before to 65.2% p.a. as at 31st March 2017, albeit this is still too high.

- West Africa Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU)

The WAEMU is a combination of eight countries in the West African region that comprises of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo. The region had witnessed a proliferation of microfinance institutions. A huge proportion of the funding for a majority of these institutions was from grants obtained from international financial institutions and their respective governments. Despite the cheap cost of funding, the cost of credit skyrocketed and as a result, there was public outcry for the reduction and capping of the borrowing rates and for regulation in terms of how microfinance institutions price credit. The region’s Central Bank capped lending rates at 15% for banks and 24% for non-banking institutions in 1997. However, after the imposition of the rate cap, many microfinance institutions withdrew from areas mainly occupied by low income households, their main clientele. This saw reduced credit accessibility by these households as microfinance institutions were unable to price these borrowers within the margins set by the Central Bank. This had the overall effect of locking out low-income borrowers, since these institutions adopted strict lending policies and focused on secured lending to larger and more “secure” borrowers, as opposed to the small borrowers that form the majority of the population. Thus, the cap had the opposite intended effects as credit accessibility was reduced for low earners. However, the interest rate cap remains in place to date. The World Bank has repeatedly called for the WAEMU to consider amending the interest rate caps, either in a partial or phased liberalization plan, coupled with increased transparency requirements and standardized disclosures, as the caps have also constrained the offer of innovative digital credit and savings products to the unbanked, thereby limiting the growth of financial inclusion.

Section IV: Our Views on the Way Forward:

It is clear to us that we need to urgently repeal or at least significantly review the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, given the current regulatory framework, as it has hampered credit growth, evidenced by the continued decline of private sector credit growth, which is at 2.1% as at March 2018, below the 5-year average of 14.0%; but a repeal ought to contain several components as there is no single silver bullet. We are however concerned that the repeal is more focused on banks, yet to manage bank dominance and funding reliance we have to focus on expanding capital markets as an alternative to banks. We see a combination of the following 7 measures as necessary as part of the repeal:

- Legislation and policies to promote competing sources of financing should be the centerpiece of the repeal legislation: A lot of legislative action has focused on the banks, yet we also need legislation to promote competing products that will diversify funding sources, which will enable borrowers to tap into alternative avenues of funding that are more flexible and pocket-friendly. This can be done through the promotion of initiatives for competing and alternative products and channels, in order to make the banking sector more competitive. In developed economies, 40% of business funding comes from the banking sector, with 60% coming from non-bank institutional funding. In Kenya, 95% of all funding is bank funding, and only 5% from non-bank institutional funding, showing that the economy is highly dominated by the banking sector and should have more alternative and capital market products for funding businesses. Alternative investment managers and the capital markets regulators need to look at how to enhance non-bank funding, such as high yield investment vehicles, some of which include High Yield Notes and Cash Management Solution, CMS, products. The products offer investors with cash to invest at a rate of about 18% to 19% per annum, equivalent to what the fund takers, such as real estate developers, would have to pay to get funds from the banks. Instead of a saver taking money to the bank and getting negligible returns, they can just invest in a funding vehicle where the business would pay them the same 18% to 19% per annum that they would pay to get the same money from the bank. For the saver, it helps improve their rate from low rates, at best 7% per annum, to as high as 18% per annum, and for the business seeking funding, it helps them access funding much faster to grow their business. Promoting alternative funding is also essential to the affordable housing piece of the “Big Four” government agenda, which requires capital markets funding,

- Consumer protection: The implementation of a strong consumer protection, education agency and framework, to include robust disclosures on cost of credit, free and accessible consumer education, enforcement of disclosures on borrowings and interest rates, while also handling issues of contention and concerns from consumers,

- Promote capital markets infrastructure: This is necessary in both regulated and private markets. The Capital Markets Authority (CMA) could aid in enhancing the capital markets’ depth by making it easier for new and structurally unique products to be introduced in the capital and financial markets. This may then enhance returns, with the benefits of reduced risk compared to the traditional conventional investment securities. This will then enable the diversion of the funds from banks into other investment vehicles that yield returns that far eclipse those obtained from deposits in banks, thereby leading to a faster capital formation in the economy. Advocacy groups, such as the East African Forum for Structured Products (EAFSP) and East Africa Venture Capital Association (EAVCA), should engage policy makers on the need for alternative and structured products as viable options to bank funding, hence reducing overreliance on bank funding and thereby spurring competition in the credit market, which would eventually lead to cheaper debt costs for borrowers,

- Addressing the tax advantages that banks enjoy: Level the playing field by making tax incentives available to banks to be also available to non-bank funding entities and capital markets products such as unit trust funds and private investment funds. For example, providing alternative and capital markets funding organizations with the same withholding tax incentives that banking deposits enjoy, of a 15% final withholding tax so that depositors don’t feel that they have to go to a bank to enjoy the 15% withholding tax; alternatively, normalize the tax on interest for all players to 30% to level the playing field,

- Consumer education: Educate borrowers on how to be able to access credit, the use of collateral, and the importance of establishing a strong credit history,

- The adoption of structured and centralized credit scoring and rating methodology: This would go a long way to eliminate any biases and inconsistencies associated with accessing credit. Through a centralized Credit Reference Bureau (CRB), risk pricing is more transparent, and lenders and borrowers have more information regarding credit histories and scores, thus enabling banks price customers appropriately, spurring increased access to credit,

- Increased transparency: This can be achieved through a reduction of the opacity in debt pricing. This will spur competitiveness in the banking sector and bring a halt to excessive fees and costs. Recent initiatives by the CBK and Kenya Bankers Association (KBA), such as the stringent new laws and cost of credit website being commendable initiatives,

In conclusion, a free market, where interest rates are set by market participants coupled with increased competition from non-bank financial institutions for funding, will see a more self-regulated environment where the cost of credit reduces, as well as increased access to credit by borrowers that have been shunned under the current regime. Consequently, a repeal is necessary, but the repeal needs to be comprehensive and contain the 7 elements above for it to be effective, but the center-piece of the legislation should be stimulating capital markets to reduce banking sector dominance, yet this key piece seems to be missing in the current draft discussions.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the writers where particulars are not warranted. This publication, which is in compliance with Section 2 of the Capital Markets Authority Act Cap 485A, is meant for general information only and is not a warranty, representation, advice or solicitation of any nature. Readers are advised in all circumstances to seek the advice of a registered investment advisor.