Jun 23, 2019

This week, we revisit the interest rate cap topic following the proposal by the National Treasury Cabinet Secretary, Mr. Henry Rotich, in the Budget reading for 2019/20 fiscal year, to repeal Section 33B of the Banking Act, which capped interest chargeable on loans at 4.0% above the CBR rate. As highlighted in the Finance Bill 2019, the proposition to repeal the interest rate cap stems from the adverse effects the law has had on credit access, especially by the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), which consequently has detrimental effects on economic growth.

In 2018, the Parliament rejected a similar repeal proposition made by the Cabinet in the Finance Bill 2018, electing to retain the lending rate cap ceiling but scrapping off the deposits rate floor, which was set at 70.0% of the Central Bank Rate. According to the Treasury, in order to spur business activity and improve access to credit to the private sector that is largely made of MSMEs, there is a need to repeal the rate cap law. The Central Bank of Kenya (CBK), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), also support the repeal of the interest rate cap, citing that the law has not achieved its intended objectives.

We, therefore, revisit the issue of the interest rate cap, focusing on:

- Background of the Interest Rate Cap Legislation - What Led to Its Enactment?

- A Recap on Our Analysis on the Subject

- A Review of the Effects It Has Had So Far in Kenya

- Case Study of Interest Rate Cap Regime - Zimbabwe

- Recent Developments

- Our Views, Expectations, and Conclusion

Section I: Introduction

- Background of the Interest Rate Cap Legislation - What Led to Its Enactment?

Controls in the banking sector date back to the post-independence period where between 1963 and 1970, the government pursued a regime of interest rate capping and quantitative credit controls, with the aim of encouraging investment and spurring economic growth and development. The controls fixed minimum saving rates for all deposit-taking institutions and maximum lending rates for lending financial institutions, which resulted in fixed interest spreads for banks. This was largely aimed at improving the aggregate savings level, by incentivizing depositors using relatively higher deposit rates. Control of lending rates, on the other hand, resulted in the suppression of financial intermediation, which consequently changed banks’ operating models, and they became biased towards short-term credit to parastatals and major firms.

The enactment of the Banking (Amendment) Act 2015 in September 2016, that capped lending rates at 4.0% above the Central Bank Rate (CBR), and deposit rates at 70.0% of the CBR, came against a backdrop of low trust in the Kenyan banking sector due to various reasons:

- The period was marred with several failures of banks such as Chase Bank Limited, Imperial Bank Limited and Dubai Bank, due to failures in corporate governance. The failure of these banks rendered depositors helpless and unable to access their deposits in these banks,

- The total cost of credit was high at approximately 21.0% per annum, yet on the other hand, the interest earned on deposits placed in banks was low, at approximately 5.0% per annum, and

- Calls for capping interest rates were based on the high profitability in the banking sector because of high spreads between lending rates and deposits rates, which in 2016 was at a high of 9.5%. As a result, in 2016, the Return on Equity of Kenyan banks stood at 24.5% above the 5-year SSA average of 15.4%. The Return on Assets, on the other hand, stood at 3.1% above the 5-year SSA average of 1.5%.

Section II. A Recap on Our Analysis on the Subject

Our view has always been that the interest rate cap regime would have an adverse effect on the economy and by extension to Kenyans. We have previously written about this in six focus notes, namely:

- Interest Rate Cap is Kenya's Brexit- Popular But Unwise, dated 21st August 2016, highlighted our view that the interest rate cap would have a clear negative impact on the economy. We noted that free markets tend to be strongly correlated with stronger economic growth, emphasized by the lack of compelling evidence of an economy where interest rate capping was successful, as evidenced by the World Bank report on the capping of interest rates in 76 countries around the world. In Zambia, for example, interest rate caps were introduced in December 2012 and repealed 3-years later, in November 2015, after the impact was found to be detrimental to the economy. We called for the implementation of a strong consumer protection agency and framework, coupled with the promotion of initiatives for competing alternative products and channels.

- Our second topical, Impact of the Interest Rate Cap, dated 28th August 2016, four days after the interest rate cap bill was signed into law, highlighted the immediate effects of the interest rate cap, as banking stocks lost 15.6% in 2-days. Here, we re-iterated our stance on the negative effects of the interest rate cap, while identifying the winners and losers of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015.

- The State of Interest Rate Cap, dated 14th May 2017, 9-months after the interest rate cap was signed into law. We assessed the interest rate cap and its effects on private sector credit growth, the banking sector, and the economy in general, following concerns raised by the IMF. We noted that the law had the effect of (i) inhibiting access to credit by SMEs and other “small borrowers” whom banks cited as being “risky”, and were unable to be fitted within the 4.0% margin imposed by the Law, and (ii) contributed to subduing of private sector credit growth, which was recorded at 4.0% in March 2017. We suggested that policymakers review the legislation, highlighting that there existed, and continues to exist, opportunities for structured financial products and private equity players to come in and provide capital for SMEs and other businesses to grow, and consequently improve private sector credit growth.

- In the Update of Effect on Interest Rate Caps on Credit Growth and Cost of Credit, dated 23rd July 2017, approximately 1-year after the Banking (Amendment) Act 2015 was signed into law, we analyzed, on the back of the rate cap, the decline in private sector credit growth and lending by commercial banks, coupled with the elevated total cost of credit, which was higher than the legislated 14.0%, as banks loaded excessive additional charges, while noting that the large banks, which control a substantial amount of the banking sector loan portfolio, were the most expensive. We suggested (i) a repeal or modification of the interest rate cap, (ii) increased transparency on credit pricing, (iii) improved and more accommodating regulation, (iv) consumer education, and (v) diversification of funding sources into alternatives.

- In our note titled The Total Cost of Credit Post Rate Cap, dated 14th January 2018, we analyzed the true cost of credit, the initiatives put in place to make credit cheaper and more accessible, the impact of the interest rate cap on private sector credit growth, and we gave our view on what more can be done to remedy the effects of the interest rate cap.

- In Rate Cap Review Should Focus More on Stimulating Capital Markets, dated 13th May 2018, we revisited the interest rate cap following an announcement by the Treasury that they were in the process of completing a draft proposal that will address credit management in the economy, where we gave our views on how promoting competing sources of financing would lead to a self-pricing regulatory structure, which would effectively reduce credit prices, as opposed to relying on bank funding.

- In our note on the Status of the Rate Cap Review in Finance Bill 2018, 26th August 2018, we revisited the interest rate cap topic following the proposed amendments to the Finance Bill, 2018, tabled by the Parliamentary Committee on Finance and Planning in the National Assembly during its second reading.

Section III: A Review of the Effects It Has Had So Far in Kenya

The interest rate cap has had the following four key effects to Kenya’s Economy since its enactment:

- Private Sector Credit Crunch

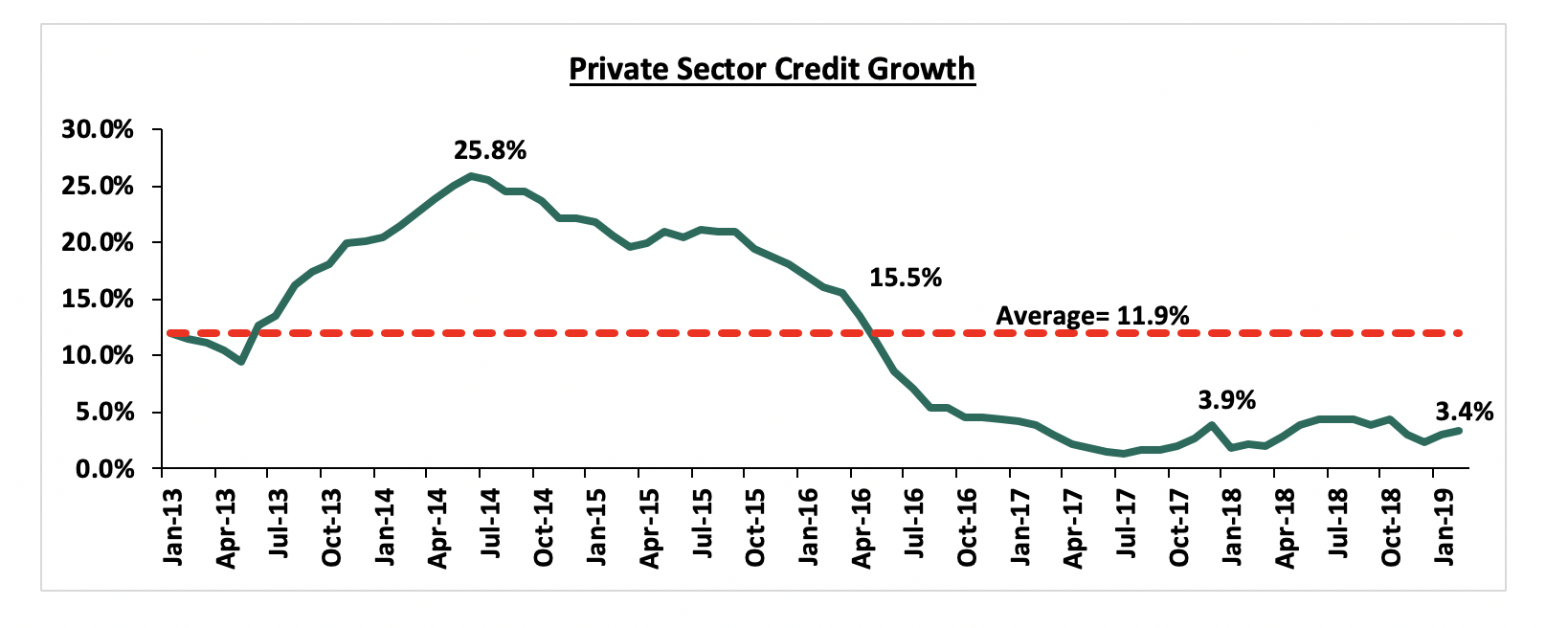

Private sector credit growth in Kenya has been declining, and the enactment of the Banking (Amendment) Act (2015), had the adverse effect of further subduing credit growth. The stock of credit to SMEs declined sharply by 10% y/y in October 2017 from a similar period in 2016 on account of difficulty for banks to price the SMEs within the set margins, as they were perceived “risky borrowers”. Banks thus invested in asset classes with higher returns on a risk-adjusted basis, such as government securities. Lending to the public sector increased sharply with a growth of over 25% y/y over the same period. Private sector credit growth touched a high of 25.8% in June 2014, and averaged 11.8% over the last five years, but dropped to below 5.0% after the implementation of interest rates controls, rising slightly to 3.4% in February 2019. The chart below highlights the trend in private sector credit growth.

- Loan Accessibility Reduced

Following the enactment of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, banks recorded a rise in demand for loans, as did the number of loan applications, which increased by 20.0% in Q4’2016, according to the CBK Credit Officer Survey of October-December 2016. This was on account of borrowers attempting to access cheaper credit. However, the supply of loans by banks did not meet this rise in demand as evidenced by:

- Reduced Loan Growth: According to the Bank Supervision Annual Report 2017, the Net Loan growth declined since the implementation of the interest rate cap law, having come from a growth of 11.2% in 2015 to a decline of 7.7% as at December 2017.

- The decline in the number of loan accounts: The number of loan accounts in large banks (Tier I) declined by 27.8%, the largest among the three tiers, followed by Tier II banks with a decline of 11.1% between October 2016 and June 2017,

- Increase in average loan size: Despite a 26.1% decline in the industry’s number of loan accounts between October 2016 and June 2017, the average loan size increased by 36.0% to Kshs 548,000 from Kshs 402,000 between October 2016 and June 2017. This points to lower credit access by smaller borrowers, while also demonstrating that credit was extended to larger and more “secure” borrowers, and,

- Decrease in average loan tenures: The average loan tenure declined by 50.0% to 18-24 months compared to 36-48 months prior to the introduction of the interest rate cap. This is due to bank’s increasing their sensitivity to risk, thereby opting to extend only short-term and secured lending facilities to borrowers, rather than longer-term loans to be used for investments, according to the latest survey by the Kenya Bankers Association (KBA) on the effects of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015.

- Banks’ Changed their Operating Models to Mitigate the Effects of the Rate Cap Legislation

The enactment of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, saw banks changing their business and operating models to compensate for reduced interest income (their major source of income) as a result of the capped interest rates. Thus, banks adapted to this tough operating environment by adopting new operating models through:

- Increased focus on Non-Funded Income (NFI): This is evidenced by the fact that the proportion of non-interest income to total income stood at 28.4% in September 2016, and has risen to the current average of 36.0%, for listed commercial banks that have released their Q1’2019 financial results,

- Increased lending to the government rather than individuals and the private sector: This is evidenced by the faster growth in allocations to government securities by 16.1% as at Q1’2019, faster than the 7.7% growth in loan allocations, given the higher risk-adjusted returns offered by government debt.

- Cost rationalization: Banks also stepped up their cost rationalization efforts by increasing the use of alternative channels by mainly leveraging on technology such as mobile money and digital banking to improve efficiency and consequently reduce costs associated with the traditional brick and mortar approach. This led to the closure of branches and staff layoffs in a bid to retain the profit margins in the tough operating environment, due to depressed interest income, and,

- Focus on niche segments: The implementation of the law saw the larger banks venture into the small banks’ niche markets such as Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) banking, and consequently, most of the tier II and tier III banks have struggled to operate. The smaller banks have witnessed declining top-line revenue, leading to increased operational inefficiency, and operating losses; this has led to depleted capital, spurring an increase in the consolidation activity in the banking sector, which has seen smaller banks struggling to operate being acquired, merging or forming strategic relationships with larger banks in order to leverage on the synergies created.

- The Proliferation of Alternative Credit Markets

As a result of the private sector credit crunch, there was a rapid rise in the alternative credit markets as evidenced by the Mobile Financial Services (MFS) rising to become the preferred method to access financial services in 2019, with 79.4% of the adult population using the channels up from 71.4% in 2016. According to Global Digital, in 2018, there were about 6.1 mn digital borrowers in the country coupled with 28.3 mn unique mobile users. Players in this segment charge exorbitant interest rates, e.g. M-Shwari charges a facilitation fee of 7.5%, while Tala and Branch offer varying rates depending on the repayment period with a month’s loans offered at a rate of 15.0%, which are very expensive when annualized.

- Reduced Effectiveness of the Monetary Policy

The introduction of interest rate controls has made it difficult for the CBK to adjust the monetary policy rates in response to economic developments. Before the interest rates were capped, the CBK was able to adjust the CBR in relation to changes in inflation and growth. This is mainly because any alteration to the CBR would directly affect credit conditions. Expansionary monetary policy is difficult to implement since lowering the CBR has the effect of lowering the lending rates and as a consequence, banks find it even more difficult to price for risk at the lower interest rates, leading to pricing out of even more risky borrowers, and hence further reducing access to credit. On the other hand, if the CBK was to employ a contractionary monetary policy, so as to reduce inflation and credit growth for example, then raising the CBR would have the reverse effect of increasing the supply of credit in the economy since banks would be able to admit riskier borrowers.

Section IV: Case Study of Interest Rate Cap Regime in Zimbabwe

- Background

Between 1980 and 1999, the financial sector of Zimbabwe was characterized by administrative controls on deposit and lending rates that were frequently adjusted to take into account rising inflation rates. During this period, the average annual economic growth rate was 2.7%, below the population growth rate of 3.0%.

In 2015, an interest rate ceiling was introduced which was effected on 1st October the same year, where the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe directed that commercial banks cap interest rates at 18.0%, for both existing and new borrowers, as part of measures to deal with the prohibitive cost of finance following dollarization. Prior to the rate cap, local commercial banks were charging interest rates as high as 35.0% similar to what Kenyan commercial banks were charging before the rate cap. The model of the rate charged under the ceiling depended on the risk profiles of customers where prime borrowers with low credit risk were to be charged between 6.0% and 10.0% per annum, borrowers with moderate risk were to be charged between 10.0% and 12.0% per annum and lastly, borrowers with high credit risk were to be charged between 12.0% and 18.0% per annum, respectively. Further, housing finance loans attracted annual interest rates of between 8.0% and 16.0% per annum while loans for consumptive purposes were quoted at between 10.0% and 18.0%. Defaulters, on the other hand, were charged a penalty from 3.0% to 8.0% over and above the interest rates they would have been charged for the loans obtained.

In 2017, effective from April 1st, the interest rate ceiling dropped to a maximum of 12.0% and ranged between 6.0% and 12.0%, respectively, depending on the risk profile of each customer. Further, the charges including application, facility and administration fees were capped at 3.0%. The decline in the interest rate cap was attributed to a move by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe to reduce the lending rates to a level that was comparable with the rest of the region. This was driven by aims to improve credit consumption for the purpose of driving production across sectors and other auxiliary activities. The Central Bank also engaged the Banker’s Association of Zimbabwe to reduce interest rates on loans for productive purposes to make lending cheaper for producers with the goal of exporting products.

In February 2019, the Governor of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, John Mangudya, indicated that the Central Bank was in the process of introducing a bank rate which is expected to guide interest rates in the market. The bank rate will be used as a monetary policy instrument to control liquidity in the market. The move comes after the outcry of local commercial banks who complain that the set interest rate of 12.0% had been overtaken by inflation, which was at a high of 56.9% in the month of February, making it difficult for them to lend.

- Performance of Commercial Banks since 2015

In 2015, bank lending to individuals and manufacturing accounted for 22.0% and 19.8% total loans, respectively. In 2017, however, the distribution of loans to individuals and manufacturing sectors declined to 18.6% and 17.3%, respectively. Total banking sector gross loans & advances decreased by 2.6% from USD 3.9 bn in 2015 to USD 3.8 bn in 2017 on account of reduced lending rates. On the other hand, fees and commission income in the banking industry rose by 51.2% to USD 512.5 mn in 2018 from USD 339.0 mn recorded in 2015, owing to hidden loan charges, despite the 3.0% cap on application, facility and administration fees charged by banks in 2017.

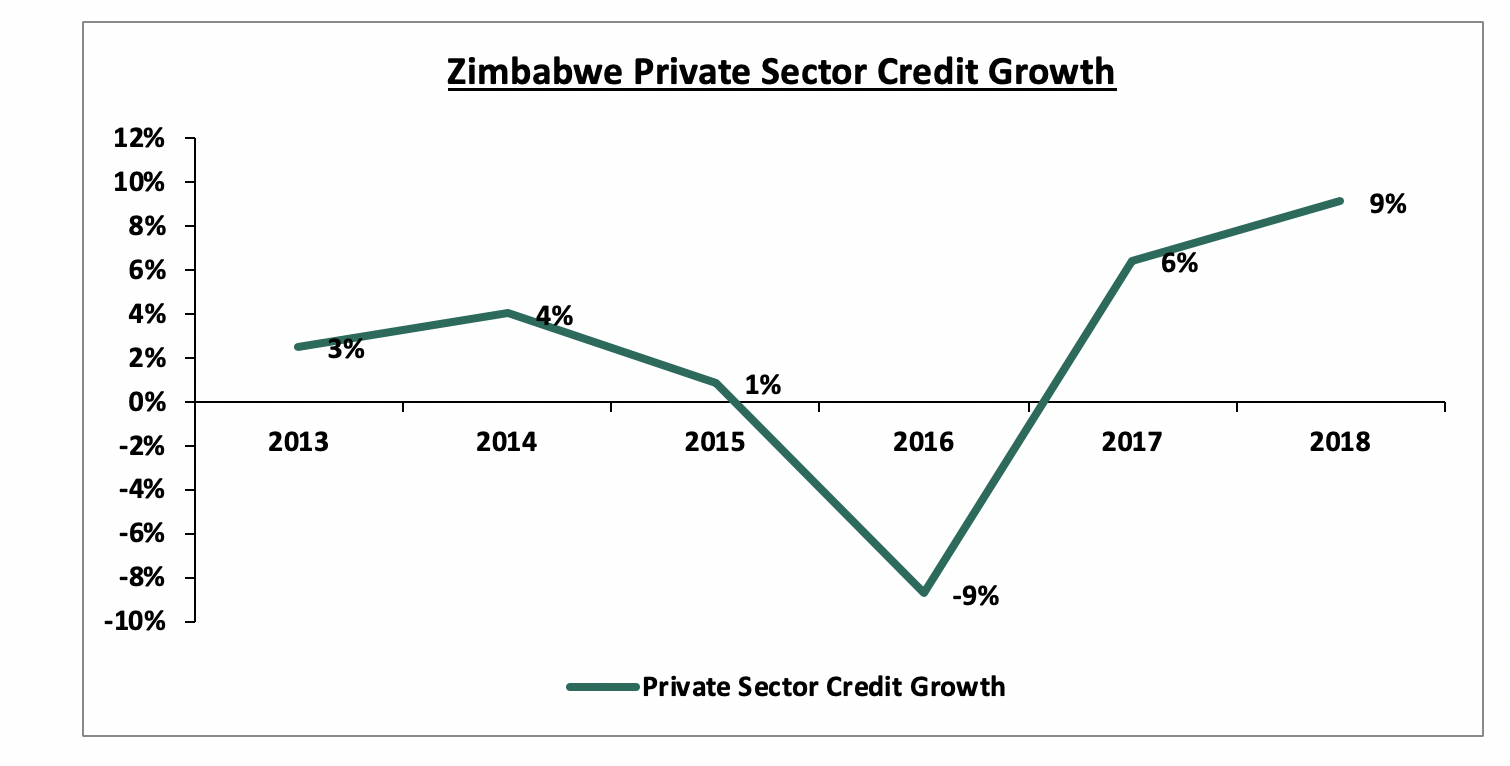

Zimbabwe’s lending rates ceiling generally aimed to target predatory lending that arose when the economy was dollarized in 2009 and banks took advantage of the different currencies in the economy to price their loans based on Zimbabwean dollar and not US dollar based as required. This reduced transparency resulted in local commercial banks charging interest rates as high as 35.0%. The lending cap has impacted the banking industry as evidenced by a credit crunch towards the private sector, similarly observed in Kenya. The private sector credit growth in Zimbabwe was at 4% in 2014 before the rate ceiling, which then slumped to negative 9% in 2016 at the height of the interest rate cap as shown below.

As highlighted, bank lending to individuals and manufacturing in 2017 recorded declines to 18.6% and 17.3%, respectively from 22.0% and 19.8% in 2015 when the rate ceiling was implemented. Specifically, the cap affected the manufacturing sector, with a bias to producers of chemicals and petroleum products, wood and furniture, metal and metal products, clothing and footwear, and non-metallic mineral products, among others.

Section V: Recent Developments

- Removal of the floor in the Finance Act 2018

The Finance Bill 2018 was tabled by the Parliamentary Committee on Finance and Planning in the National Assembly during its first reading with proposed amendments to repeal Section 33B of the Banking Act which would result in the elimination of the Central Bank’s powers to enforce an interest rate cap in banks and other financial institutions. During the second reading of the bill in parliament, however, the committee was of the view that:

- The upper limit on the interest rate charged on borrowers, which is capped at 400 basis points above the CBR, should be maintained, stating that there is no justification for the repeal of the cap, as banks have not shown efforts to address the issue of high credit risk pricing, and,

- The floor set for deposit rates paid to depositors at 70% of the CBR should be repealed. The proposition to remove the floor was ratified by the National Assembly and consequently signed into law as part of the Finance Act 2018.

- High Court Ruling on Interest Rate Capping

On 18th March 2019, the High Court suspended the Interest Rate Cap law in a ruling that declared Section 33B (1) and (2) of the Banking Act unconstitutional and gave the National Assembly one year to amend the anomalies, failure to which will mean a reversion to a free-floating interest rates regime. A three-Judge bench determined that the wordings the Parliament used to define the terms ‘credit facility’ and the ‘Central Bank Rate’ as vague and open to multiple interpretations. The anomalies and ambiguity arise in Section 33B (1) of the Banking Act which states that, “a bank or a financial institution shall set the maximum interest rate chargeable for a credit facility in Kenya at no more than four percent, the Central Bank Rate set and published by the Central Bank of Kenya (now at 9.0%)”.

- Proposal to Repeal the Cap by the National Treasury Cabinet Secretary

The National Treasury Cabinet Secretary, Henry Rotich, stated that in this year’s Finance Bill, another proposal would be tabled to seek the repeal of Section 33B of the Banking Act 2016, as the interest rates cap has had the opposite effect of reducing credit access by MSMEs, in addition to contributing to the shrinking of small banks’ loan books. The Cabinet Secretary maintains its view that in order to spur business activity and improve access to credit by MSMEs and the private sector in general, there is a need to repeal the rate cap law.

- Calls by various organizations to repeal the Rate Cap Law

- IMF

The International Monetary Fund backed the National Treasury and CBK’s call for the repeal of the interest rates cap law. The IMF working paper released in March 2019 termed the interest rate controls Kenya introduced in September 2016 as the most drastic measures ever imposed. According to the paper, the reduction of the interest rate spreads, which initially was intended to increase access to bank credit and boost the return on savings, seems to have the opposite effect evidenced by;

- A sharp decline in bank credit to SMEs, particularly in trade and agriculture,

- A disproportional hit on lending activity and the profitability of small banks; and

- Reduced financial intermediation, with commercial bank credit shifting away from the private sector and towards the public sector.

The paper also points out the reduced signaling effect of the policy rate as an indicator of the monetary policy stance due to the increased divergence of interbank rates from policy rates following the implementation of the interest rates cap. The paper proposed that consideration should be given to using other policy instruments, instead of interest rate controls, to increase financial access and address equity concerns related to the high profits of the banking sector.

- Kenya National Chamber of Commerce and Industry

The Kenya National Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KNCCI) has backed the proposal to repeal the commercial lending rate caps law with the view that that the removal of the cap will provide an added incentive to banks to loosen risk considerations before extending credit to SMEs, thus improving credit access by small businesses.

Section VI: Our Views, Expectations, and Conclusion

The proposal to repeal Section 33B of the Banking Act (2016) by the Cabinet Secretary will be tabled in the form of Bills before it is introduced to the National Assembly, thereafter it will be assigned to a committee where it will be read for the first time. The bill will go through the Second and Third Reading stages before final approval or rejection is given by Parliament. Thereafter, the President will give assent to the Act of Parliament, which subsequently will be gazetted to become law. If the proposal to repeal the rate cap law is successful, we expect to see the following benefits accrue to the economy:

- Growth in private sector credit: As of April 2019, the private sector credit growth rate stood at 4.9% according to the MPC market perception survey. With the repeal of the rate cap law, we expect that access to credit by Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) will increase as banks will have sufficient margin to compensate for risks,

- GDP growth: Credit and economic growth are positively correlated and we expect that with increased access to credit by MSMEs, the economy is bound to expand as MSMEs make a significant contribution to the economy. According to data from the KNBS Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) 2016 survey, MSMEs account for approximately 28.4% of Kenya’s GDP, and,

- Increased monetary policy effectiveness: With the repeal of the rate cap law, the Central Bank of Kenya will be free to adjust the monetary policy rate in response to economic developments such as inflation and growth.

In conclusion, we continue to emphasize the need to urgently repeal or at least significantly review the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, given the current regulatory framework, as it has hampered credit growth, evidenced by the continued decline of private sector credit growth, which is at 4.9% as at April 2019, below the 5-year average of 14.0%. Some policy measures, other than interest rate caps, that can both protect borrowers from excessive interest rates and limit the negative consequences of interest rate caps include:

- The adoption of structured and centralized credit scoring and rating methodology: This would go a long way to eliminate any biases and inconsistencies associated with accessing credit. Through a centralized Credit Reference Bureau (CRB), risk pricing is more transparent, and lenders and borrowers have more information regarding credit histories and scores, thus enabling banks price customers appropriately, spurring increased access to credit,

- Consumer education: Educate borrowers on how to be able to access credit, the use of collateral, and the importance of establishing a strong credit history,

- Increased transparency: This can be achieved through a reduction of the opacity in debt pricing. This will spur competitiveness in the banking sector and bring a halt to excessive fees and costs. Recent initiatives by the CBK and Kenya Bankers Association (KBA), such as the stringent new laws and cost of credit website being commendable initiatives,

- Greater emphasis on strengthening consumer protection measures: The implementation of strong consumer protection, education agency, and framework, to include robust disclosures on cost of credit, free and accessible consumer education, enforcement of disclosures on borrowings and interest rates, while also handling issues of contention and concerns from consumers, and

- Promote capital markets infrastructure: in both regulated and private markets. The Capital Markets Authority (CMA) could aid in enhancing the capital markets’ depth by making it easier for new and structurally unique products to be introduced in the capital and financial markets. This may then enhance returns, with the benefits of reduced risk compared to the traditional conventional investment securities. This would enable the diversion of the funds from banks into other investment vehicles that yield returns that far eclipse those obtained from deposits in banks, thereby leading to a faster capital formation in the economy, hence reducing overreliance on bank funding and thereby spurring competition in the credit market, which would eventually lead to cheaper debt costs for borrowers.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the writers where particulars are not warranted. This publication, which is in compliance with Section 2 of the Capital Markets Authority Act Cap 485A, is meant for general information only and is not a warranty, representation, advice or solicitation of any nature. Readers are advised in all circumstances to seek the advice of a registered investment advisor.