Jan 26, 2025

A Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), sometimes known as a Special Purpose Entity (SPE), is a legally separate and independent entity formed for a specific, defined purpose, typically to isolate financial risk. SPVs are widely utilized in securitization, project finance, structured finance, and asset-backed transactions. They are intended to be bankruptcy-resistant, meaning that their operations and liabilities are separate from the parent or sponsoring organization.

We chose to focus on SPVs for two reasons:

- First is Limited Understanding: Given their limited understanding in the local market, yet they are crucial to bringing much needed capital to fund businesses and projects. Further, the High Court in a matter for one of our associate companies, order liquidation primarily based on the fact that a Funding SPV had lent money to a project SPV without getting the typical securities a bank would get, hence calling the arrangement “a kin to a fraud”. These liquidation orders over two funding vehicles, with 4,000 investors, had financed 10 real estate projects with another 20,000 investors in the 10 projects. The liquidation orders appeared to be founded on the High Court lack of appreciation on how SPVs work, and the orders have now given risk to almost 200 matters in various courts. In his recusal ruling, Justice Alfred Mabeya said, “I do not know how I should have described that arrangement." We hope that an explanation will help the market, stakeholders and even future adjudicates understand and describe arrangements around SPVs.

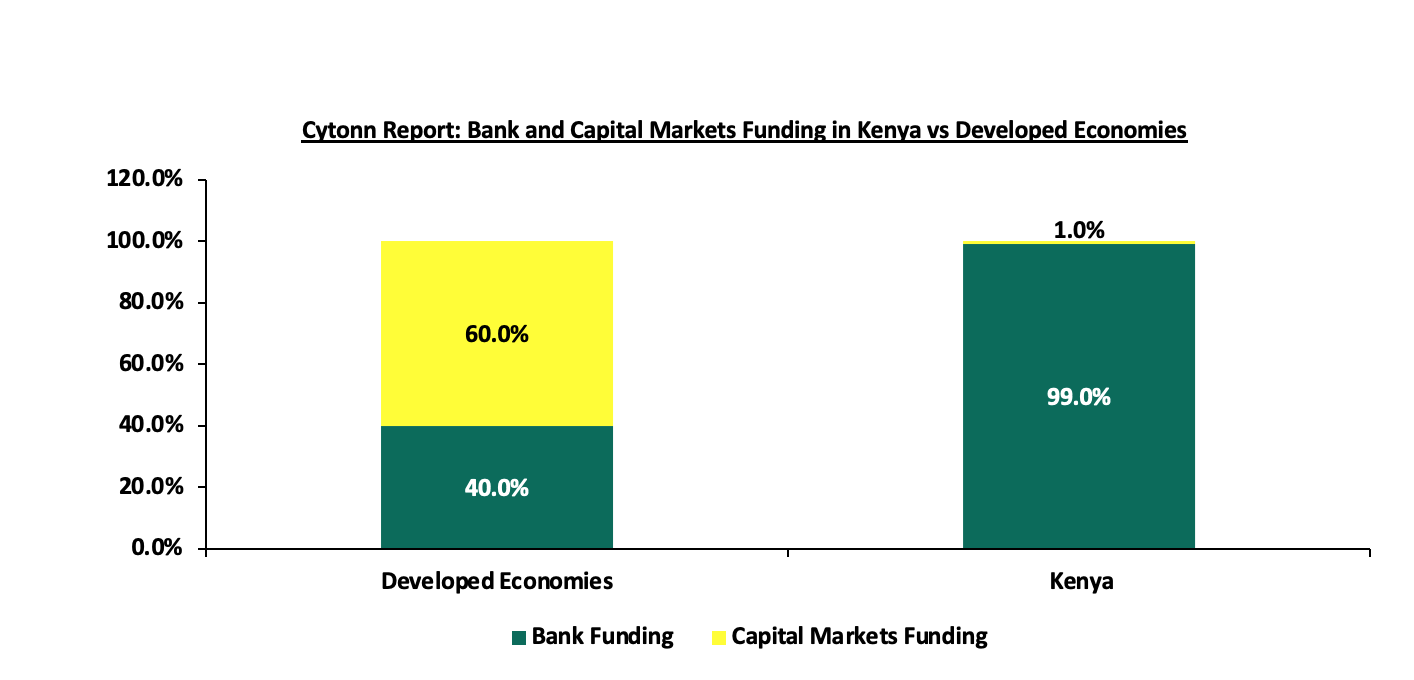

- Second is the Importance of SPVs in Funding businesses: In well developed economies such as the US, banks provide only 40% of funding for businesses while the majority 60% comes from capital markets funding by structures and instruments such as equity and debt instruments, SPVs, Special Purpose Acquisition Companies – SPACs, etc. However, in emerging market such as Kenya, banks provide 99% of capital with capital markets providing only 1% of capital. Essentially, there is bank dominance, and that is why funding for businesses is hard to find and when found, its prohibitively expensive making Kenya one of the most lucrative markets for banking business. The chart below shows a comparison of banks’ and capital markets funding in Kenya against the funding proportions for developed economies

Source: World Bank

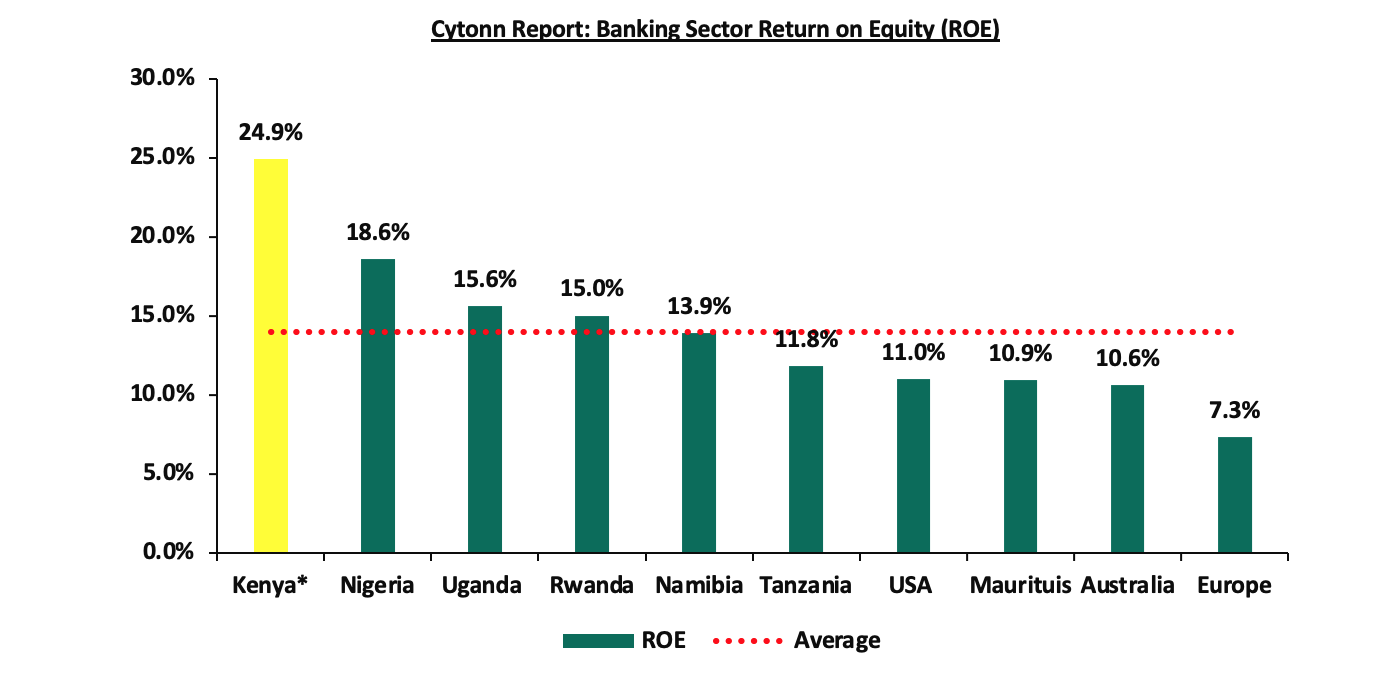

On a global level, the Kenyan banking sector continues to record high profitability compared to other economies in the world, as highlighted in the chart below:

Source: Cytonn Research, Kenya* as of Q3’2024

To try to improve understanding of SPVs, in this week’s focus, we shall look into the following;

- Introduction,

- The Overview of SPVs in Kenya,

- The Legal and Regulatory Framework for SPVs in Kenya,

- Misconceptions around SPVs in Kenya,

- Case Studies,

- Benefits of SPVS in the Kenyan Financial Ecosystem,

- Challenges and Risks Associated with SPVs in Kenya, and,

- Recommendations and Conclusion.

Section I: Introduction

- The Evolution of Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) in Global Finance and Investments

A Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), sometimes known as a Special Purpose Entity (SPE), is a legally separate and independent entity formed for a specific, defined purpose, typically to isolate financial risk. SPVs are widely utilized in securitization – which means turning projected cash flows from a project into an investable instrument, project finance, structured finance, and asset-backed transactions. Drawing from the settled trite law that a company is a separate legal entity and also captured in the celebrated case of Salomon vs. Salomon and Company Limited, SPVs are intended to be bankruptcy-resistant, meaning that their operations and liabilities are separate from the parent or sponsoring organization. It would be very messy if the bankruptcy of one entity is visited upon the other entities.

SPVs can be established as either limited liability companies (LLCs) or limited partnerships, trust or even a subsidiary of the originator. Since they operate as independent entities, they remain off the sponsor’s or parent company’s balance sheet.

Initially, SPVs were simple legal entities designed to address specific financial needs, but they have since become powerful tools for financial innovation, risk management, and strategic funding. Early applications were seen in real estate, infrastructure, and government projects. Developed countries like the U.S. and the U.K. provided the legal environments conducive to creating SPVs, leveraging their corporate law systems. In the 1990’s SPVs became central to securitization, with financial institutions using SPVs to pool assets like mortgages, loans, and credit card receivables, and issue securities backed by these assets. This innovation led to the creation of asset-backed securities (ABS) and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). However, SPVs also began to attract scrutiny due to their misuse in some cases, such as Enron’s collapse in 2001, where SPVs were used to conceal debt and inflate earnings. Notably, during the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve used an SPV to help rescue Bear Stearns by facilitating its sale to JPMorgan, invoking Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act to authorize the creating of emergency lending facilities. The financial crisis highlighted the role of SPVs in opaque transactions and excessive risk-taking, leading to the establishment of regulatory reforms, such as the Dodd-Frank Act and Basel III, that increased oversight of SPVs, requiring greater transparency and stricter capital requirements.

Additionally, during COVID -19, the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) created by the Federal Reserve, used SPVs to support the issuance of asset-backed securities and revive credit markets. Under the TALF, the Federal Reserve gave loans that didn’t require repayment if the borrower couldn’t pay, as long as the loans were backed by highly rated securities tied to new consumer and small business loans. The TALF was established by the Federal Reserve under the authority of Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, with approval of the Treasury Secretary and ceased extending credit on 31st December 2020.

The global evolution of SPVs highlights their adaptability and enduring relevance in a rapidly changing financial landscape. From basic risk management tools to key drivers of financial innovation, SPVs continue to shape the future of global finance. Countries like India and China are increasingly adopting SPV structures for infrastructure development and public-private partnerships (PPPs).

- The Evolution of Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) in Finance and Investments in Kenya

In Kenya, the adoption and development of Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) have followed global trends while being influenced by the country’s unique regulatory, economic, and infrastructural context. SPVs were first introduced in Kenya during the 1990s, primarily as a means to finance large-scale infrastructure projects. Before the mid-1990s, the only SPVs in operation were Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) such as the Commonwealth Development Corporation (CDC) and the International Finance Corporation (IFC). These institutions also established subsidiaries like the Housing Finance Company of Kenya (HFCK) and several others. After 1995, there was an increase in involvement by Development Partners (DPs), including the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID), which supported the establishment of the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG), a group of institutions legally based in Mauritius. This initiative also led to the creation of organizations such as the Financial Sector Deepening (FSD) Trust in Kenya in 2005.

Recently from 2010, SPVs gained prominence in real estate developments and securitization deals. Developers used SPVs to manage specific projects, separate liabilities, and attract investors. Similarly, financial institutions began experimenting with securitization, pooling assets like mortgages for investment products. Notable examples include:

- Cytonn Investments employing Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) to manage its real estate projects, ensuring proper governance and accountability. Each project is structured into an SPV, overseen by the Real Estate Projects (REP) Board, which provides guidance throughout the project's lifecycle. With notable projects such as the Alma, a comprehensive residential development located in Ruaka, featuring modern apartments and various amenities

- The Kenya Mortgage Refinance Company (KMRC), which was established to promote affordable housing, began experimenting with the use of SPVs to securitize mortgage portfolios. By pooling mortgages from commercial banks, KMRC aimed to create mortgage-backed securities (MBS) that could be sold to investors, which would provide more liquidity in the housing market.

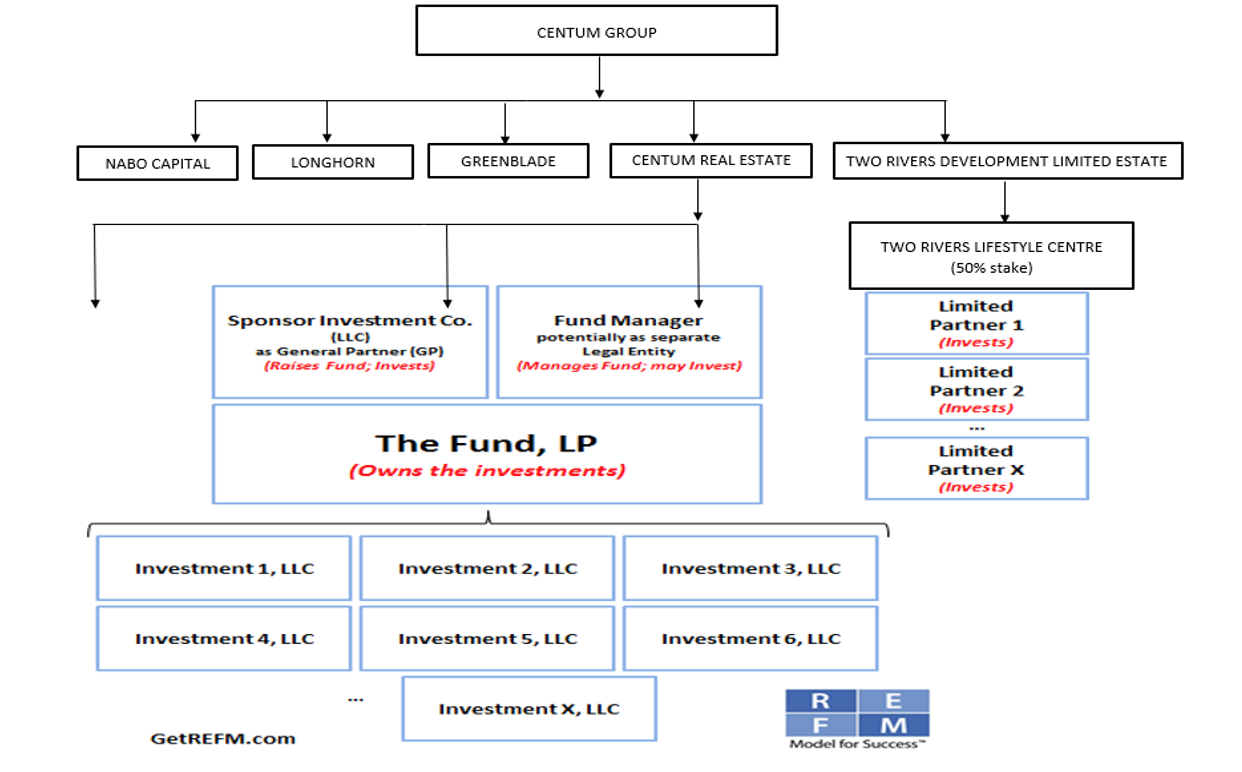

- Centum Real Estate, a subsidiary of Centum Investment Company, developed the Two Rivers Development in Nairobi, Kenya. To effectively manage and finance various components of the development, Centum utilized Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs). One significant SPV is the Two Rivers Development Limited (TRDL), which oversees the entire Two Rivers project. Within this framework, specific projects have been initiated, including Centum Real Estate securing Kshs 2.9 bn from the International Finance Corporation (IFC) to accelerate the construction of the Edge-certified Mzizi Court Apartments at Two Rivers. Centum Group has invested in a number of Real Estate projects in the country through subsidiaries and special purpose vehicles as indicated in the chart below:

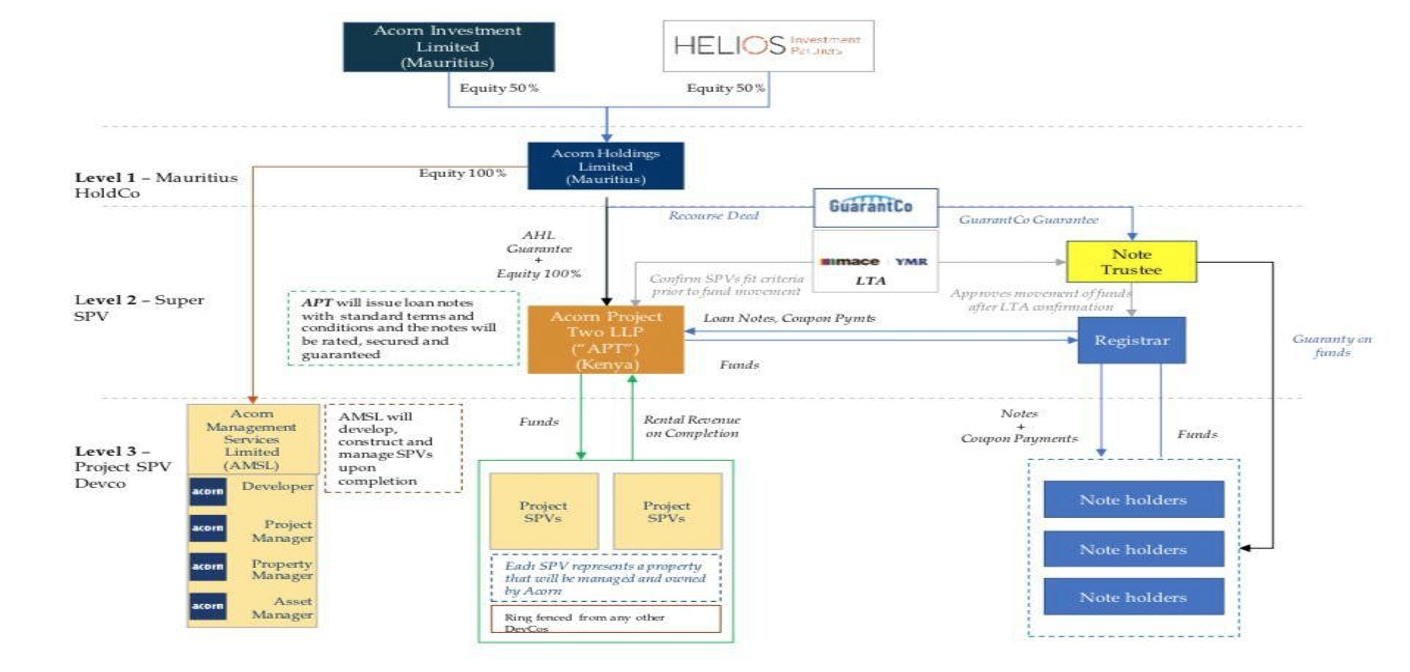

- Acorn, with equity backing from Helios through Acorn Investment Limited, uses Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) to channel funds raised from note issuances. The funds are downstreamed via Acorn Project Two LLP to individual project SPVs, which hold and manage specific real estate projects. Helios provides equity financing at the holding level, while the SPVs utilize the funds for property development, project costs, and reimbursement of pre-funded expenses, ensuring risk segregation and transparency. Upon project completion, the SPVs generate rental income to pay noteholders, demonstrating a structured investment approach supported by Helios’ capital.

In Kenya, Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) continue to play a pivotal role in financing and developing large-scale infrastructure projects. The Central Bank of Kenya has highlighted SPVs as an effective mechanism for infrastructure development, including initiatives in low-cost housing and road construction. The enactment of Kenya's Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Act, 2021 has further facilitated the use of SPVs, particularly in the energy sector. The Act recognizes the SPV structure, enabling the establishment of project finance frameworks essential for investments.

Section II: The Benefits of SPVs & Legal Forms in Kenya

Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) are widely used across different sectors globally, and in Kenya, they have become a critical tool for structuring transactions, managing risks, and fostering investment.

- Benefits of SPVs

- Risk Isolation: SPVs are primarily used to separate the financial and legal risks of a project from the parent organization. By isolating liabilities, an SPV ensures that the parent company is not adversely affected in case of project failure.

- Facilitation of Complex Projects: SPVs are instrumental in executing large-scale projects, such as infrastructure development, renewable energy projects, and real estate projects. They simplify project financing by consolidating project-specific assets, liabilities, and operations within the SPV.

- Access to Funding: An SPV allows entities to attract investors by offering a structured and transparent vehicle for their investment. The distinct legal identity of the SPV often enhances investor and financier confidence. For example, for a group company such as Cytonn with many projects, a bank may not be interested in funding the group company which in turn uses the funding for development, they will be more willing to have the project in an SPV and they lend to the SPV and take securities in the SPV and the SPV’s properties.

- Asset Securitization: SPVs are used to securitize assets such as loans, leases, or other receivables, enabling organizations to raise capital through the sale of these assets to investors. In other works, the projects cash flows of a project ring fenced in an SPV can be sold as an investment to investors.

- Asset Ownership: An SPV allows a single asset to be owned by multiple owners, this then allows it to be able to raise funding from a larger base. Given that SPVs fund large projects, ability to attract difference financiers is key. Without SPVS, large projects such as real estate projects would not be possible.

- Isolate Financial Risk: It would be hard to grow big companies that can do innovation, R&D and create jobs if the failure of one entity fails the entire company. SPVs are a modern finance tool to contain the financial risk of one project to that project alone.

- Minimal Red Tape: It allows the setting up of a project finance and funding vehicle without much red tape, and typically without government authorization required as it would be the case in raising funds through regulated vehicles.

- Clarity of Documentation and Governance: The parties will include exactly what they want done and how they want the SPV governed through a specific document.

- Containing Legal Liability: The liability for the sponsor is limited to the SPV in the event that the project fails it does not affect the rest of the group company, hence preserving value, jobs and tax base

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): In Kenya, SPVs are frequently employed in PPPs, allowing private sector entities to collaborate with the government in the development of public infrastructure and services.

- Risks Associated with SPVs

- Credit Risk: This arises if the underlying assets or counterparties (e.g. borrowers, or project sponsors) default on payments. Creditworthiness affects the SPV's ability to meet obligations, particularly in asset-backed securities or project finance.

- Liquidity Risk: SPVs often have structured payment obligations. A mismatch in cash inflows (from underlying assets) and outflows (to creditors or investors) can lead to liquidity challenges, especially if revenues are delayed or lower than expected.

- Operational Risk: Inefficiencies, fraud, or errors in the management of SPVs, such as poor documentation, oversight failures, or mismanagement of funds, can jeopardize their performance.

- Market Risk: SPVs that depend on market-linked revenues (e.g., real estate prices, interest rates, or foreign exchange rates) are exposed to fluctuations that may reduce returns or increase costs.

- Reputational Risk: Negative publicity, poor performance, or disputes involving the SPV or its sponsors can undermine investor confidence, making it harder to raise funds or sustain operations.

- Structural Risks: Poorly designed SPV structures or inadequate legal arrangements (e.g., insufficient separation of the SPV from the sponsor) can expose investors to additional risks, including legal claims against the SPV.

Section III: The Legal and Regulatory Framework for SPVs in Kenya

While still fairly new, Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) have become an integral part of Kenya's financial and infrastructural landscape, providing mechanisms for project financing, risk isolation, and investment structuring. The establishment and operation of SPVs in Kenya are guided by a range of legal and regulatory provisions designed to ensure compliance, transparency, and efficiency.

SPVs in Kenya can take various legal forms, each chosen based on the specific needs and objectives of the project. The choice of SPV structure depends on factors such as the nature of the project, risk considerations, funding requirements, and regulatory implications. These include:

- Limited Liability Companies: This is the most common form, providing a separate legal identity and limiting the liability of shareholders to their capital contributions. It is suitable for projects requiring clear ownership structures and governance frameworks. Cytonn Investments used a limited liability company structure to establish Cytonn Real Estate Project Notes LLP, which pools investor funds for real estate projects like The Alma

- Partnerships and Limited Partnerships: These forms are often used for joint ventures where parties seek to combine resources and share profits and losses according to agreed terms. Limited partnerships allow for both general and limited partners, providing flexibility in management and investment roles. In the Amu Power Coal Plant Project (Lamu), a partnership structure was initially adopted between Gulf Energy and Centum Investment to pool resources and expertise.

- Trusts: In certain cases, especially in asset securitization, SPVs may be established as trusts to hold assets for the benefit of beneficiaries, ensuring legal separation and protection of assets. Trust-based SPVs are commonly used by REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts) in Kenya, such as the Acorn Student Accommodation REIT, to secure assets for the benefit of investors.

- Joint Ventures: When multiple entities collaborate on a specific project, they may form an SPV as a joint venture, defining each party's rights, responsibilities, and profit-sharing arrangements. This structure is prevalent in large-scale infrastructure and real estate projects. The Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) involved a joint venture approach, with entities such as China Road and Bridge Corporation and Kenyan authorities coordinating through SPV structures.

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): SPVs in PPP projects are critical for structuring collaboration between the government and private investors, allowing for the financing, development, and operation of public infrastructure. The government may hold equity or participate in oversight roles within the SPV. The Nairobi Expressway Project utilized an SPV under a PPP arrangement, with China Road and Bridge Corporation taking on the development and operation roles while the government provided oversight and enabling policies.

The laws and regulations guiding SPVs in Kenya include:

- The Limited Liability Partnership Act 42 of 2011, (CAP 30)

The Limited Liability Partnership Act, No. 42 of 2011, establishes the framework for forming and operating Limited Liability Partnerships (LLPs) in Kenya. While the Act does not specifically mention Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs), entities can utilize the LLP structure to create SPVs for various purposes. Upon registration, an LLP becomes a body corporate with perpetual succession, possessing a legal identity distinct from its partners. This allows the LLP to own property, enter contracts, and conduct business in its own name. By leveraging the LLP structure, entities in Kenya can establish SPVs that benefit from limited liability, a separate legal identity, and a flexible management framework.

- The Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Act, 2021

According to Section VII of the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Act, 2021, a project company is a special purpose vehicle incorporated by a successful bidder specifically to undertake a public-private partnership (PPP) project. This incorporation ensures that the project company is a distinct legal entity, separate from the parent company, allowing for the isolation of financial and operational risks associated with the project. The Act mandates that the project company operates within the scope defined in the project agreement, adhering to the obligations and responsibilities outlined therein. The Act establishes the PPP Directorate and PPP Committee to oversee SPV operations within the PPP framework.

- The Companies Act, 2015

While the Companies Act, 2015 does not provide specific provisions for Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs), it offers the necessary legal structures for their creation. The Companies Act, 2015 facilitates the establishment of SPVs in Kenya by providing various company structures that can be tailored to serve specific purposes, governing the registration, operation and dissolution of SPVs as legal entities. Entities intending to establish an SPV must comply with the general requirements of the Act. This includes the incorporation process, which involves submitting requisite documents such as the memorandum and articles of association to the Registrar of Companies. Additionally, entities must adhere to corporate governance standards outlined in the Act, including appointing directors and company secretaries and maintaining statutory records. Furthermore, they are required to prepare and file annual financial statements and reports in accordance with the Act’s stipulations.

- The Capital Markets Authority and Capital Markets Act (Cap 485A)

The Capital Markets Act (Cap 485A) of Kenya, along with its accompanying regulations, outlines specific provisions concerning Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) engaged in capital market transactions. SPVs must obtain approval from the Capital Markets Authority (CMA) before issuing securities. This requirement ensures that all securities offerings meet regulatory standards and protect investor interests. The CMA evaluates the suitability of the SPV and the proposed issuance to maintain market integrity.

The Act mandates that SPVs provide comprehensive information to investors, including detailed financial statements and disclosures of potential risks associated with the investment. This transparency is crucial for informed decision-making by investors and is enforced through regulations such as the Capital Markets (Public Offers, Listings and Disclosures) Regulations, 2023. Additionally, the CMA regulates the issuance of Asset-Backed Securities by SPVs to ensure investor protection and market stability. In 2017, the CMA issued a Policy Guidance Note (PGN) to facilitate the issuance of ABS, providing clarity on the structure and operation of SPVs in such transactions.

- The Tax Regulations

The Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) does not provide specific tax regulations exclusively for Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs). Instead, SPVs are subject to the general tax framework applicable to all corporate entities in Kenya. This includes obligations related to corporate income tax, value-added tax (VAT), withholding tax, stamp duty, and turnover tax (TOT), depending on the nature of the SPV’s activities.

SPVs are required to pay corporate income tax at a rate of 30.0% on taxable income and must file annual tax returns with the KRA. If an SPV’s annual turnover exceeds Kshs 5.0 mn, it must register for VAT, which is charged at a standard rate of 16.0%, though exemptions and reduced rates may apply to certain goods and services. Additionally, SPVs are required to withhold tax on specific payments such as dividends, interest, and royalties, with rates varying based on the recipient's residency and the nature of the payment. Transactions involving property transfers, share transfers, or certain financial instruments may attract stamp duty, with rates dependent on the transaction's value and type. SPVs with an annual gross turnover between Kshs. 1.0 mn and Kshs. 25.0 mn are subject to turnover tax (TOT) at a rate of 1.0% on gross monthly sales, though some income types like rental income and professional fees are exempt from TOT.

While SPVs follow general tax regulations, the specific activities and structures of the SPV, such as those related to securitization or asset-backed securities, may influence their tax obligations.

- The Insolvency Act, 2015

The Insolvency Act, 2015 provides mechanisms for handling financial distress in SPVs. As SPVs are typically incorporated entities under Kenyan law, they are subject to the general insolvency framework applicable to all companies. This includes procedures for administration, liquidation, and arrangements with creditors as outlined in the Act. Therefore, while there are no SPV-specific insolvency provisions, the standard insolvency processes and protections apply to SPVs in Kenya. The Act outlines procedures for placing insolvent SPVs under receivership or liquidation.

Section IV: Misconceptions around SPVs in Kenya

Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) are structured financial entities created to isolate risk and achieve specific financial objectives. In Kenya, SPVs are increasingly being adopted in areas such as real estate development, project financing, and securitization of assets. However, there are several misconceptions about SPVs that hinder their adoption and proper utilization:

- SPVs are only for large corporations or multinationals: Many people in Kenya believe that SPVs are tools exclusively designed for large corporations, international organizations, or governments. In reality, SPVs are accessible to a wide range of entities, including small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), partnerships, and even individual investors. For example, an entrepreneur who owns 20 matatus, instead of having them all owned in one company, they can have each matatu owned by a different company hence have 20 different companies. The risks of each matatu are contained in that specific matatu.

- SPVs are illegal or used to evade taxes: Some stakeholders associate SPVs with tax evasion, fraud, or illegal financial practices. In reality, SPVs are legitimate financial tools used in compliance with existing laws. In Kenya, SPVs must adhere to the Limited Liabilities Partnerships Act, Companies Act, the Capital Markets Authority (CMA) regulations, and tax laws. Properly structured SPVs provide clarity to both regulators and investors. Any abuse arises from poor governance rather than the inherent nature of SPVs.

- SPVs are only for avoiding liabilities: Many believe that SPVs are merely tools to shift liability from the parent company to avoid responsibility in case of failure. In reality, while SPVs indeed ring-fence liabilities, their primary purpose is to isolate risks tied to a specific project, ensuring the financial health of the parent company. By isolating risks, SPVs can attract more investors who may be reluctant to invest in the broader entity but are willing to back a specific, well-defined project.

- SPVs guarantee project success: Some stakeholders believe that creating an SPV automatically ensures the success of a project. In reality, SPVs are tools, not guarantees. Their success depends on proper management structures and oversight, the viability of the project and proper risk management.

- SPVs lack transparency: Some believe that SPVs are opaque and prone to misuse, hiding critical information from stakeholders. In reality, properly structured SPVs enhance transparency by isolating finances and governance for specific projects. Lack of transparency occurs when governance is weak or when parties misuse the SPV to obscure transactions, which is a regulatory and management issue rather than an issue inherent to SPVs

- SPVs are a form of tax avoidance: There is a perception that SPVs are created solely to avoid taxes. However, SPVs are subject to the same tax laws as any other entity in Kenya. The perception of tax avoidance often arises when SPVs are misused, not because of their inherent structure.

Addressing misconceptions around SPVs in Kenya requires enhanced financial literacy, strong regulatory oversight, and public awareness of their benefits. SPVs are not inherently complex or exclusive tools for large organizations; they are flexible vehicles that can promote investment, manage risk, and enable innovation across various sectors. For SPVs to fulfill their potential, stakeholders must move beyond these misconceptions and focus on leveraging them to unlock Kenya’s economic growth.

Section V: Case Studies

- Cytonn High Yield Solutions (CHYS)

Cytonn High Yield Solutions (CHYS) was established as a privately placed, high-return investment product, structured as a limited Liability Partnership (LLP). The primary objective of CHYS was to by pass borrowing from banks at 18% to fund real estate development, but instead borrow directly from investors and pay them the same 18% that a project would pay to bank; essentially providing investors with higher returns compared to traditional cash management options, leveraging the potential of alternative investments like Real Estate. CHYS was offered to investors as restricted private offers as defined in Regulation 21 of the Capital Markets (Securities) (Public Offers, Listings, and Disclosures) Regulations 2002 as read together with Capital Markets Act, Section 30A(3)(b). The structure enabled CHYS to pool private client funds, invest strategically and offer direct access to high yield opportunities typically unavailable to retail investors. While Investors in CHYS participated as Investment Partners, they elected a Board to represent their interests, ensuring participatory governance and transparency in decision-making.

The funding model adopted by CHYS entailed consolidating investments from clients into a single pool and investing in alternative opportunities such as Real Estate through Loan Note Instruments, which lent from the CHYS fund to the real estate projects. In comparison, the traditional way of investing involves a saver taking money to the bank and gets little to no return on their deposit; with the bank in turn lending to, for example, a developer, and charges the market rate cost of borrowing. The bank then benefits from the difference between the cost of the deposit paid to saver and the yield from the developer. In the CHYS scenario, the process remains the same as the traditional way except that the intermediary is not a bank but an investment vehicle. The saver takes money to an investment professional through an investment vehicle (CHYS), who gives money directly to the developer. The developer will still pay the usual cost of borrowing, but instead of paying to the bank, it will be paid to the Investment Vehicle in this case CHYS, which will in turn pass returns to the saver.

The CHYS investment portfolio was diversified to include a mix of real estate projects to capitalize on the robust performance of this asset class which has historically offered returns of 25.0%-28.0% outperforming traditional investment classes such as equities and fixed-income securities. For example, a portion of the funds in CHYS was invested as mezzanine notes in The Alma in Ruaka, a Kshs 6.0 bn 450-unit mixed-use development, yielding an annualized return of approximately 25.0 % per annum supported by through market research and sound risk assessments in the project. The Alma apartments in Ruaka (Cytonn Integrated Project LLP) leveraged pre-sales contracts to maintain liquidity and meet its debt obligation to investors (CHYS). In turn, CHYS offered investors returns of up to 18.0% per annum supported by the alternative investments such as real estate-backed mezzanine debt.

On governance and transparency CHYS was structured as a Limited Liability Partnership (LLP) with investors coming in as Investment Partners. For governance, the CHYS investors had their elected Board where they voted Partners among themselves to represent them in the Board which directs investment decisions. The Board was responsible for convening Annual General Meetings (AGMs), reviewing and approving audited financial statements, and making key resolutions. Additional oversight was provided by Standard Chartered as the custodian of partner assets and Grant Thornton, which conducted annual audits. This governance framework ensured accountability and transparency in managing investor funds.

List most real estate funds, CHYS ran into liquidity challenges at the onset of Covid 19 when there was mass withdrawal of funds, limited investment into the fund and limited inflows from the real estate projects it had lent to.

Key Lessons drawn from CHYS:

- Liquidity Management: A key lesson from CHYS was the importance of liquidity management. The onset of the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 strained the liquidity of real estate funds globally and several real estate funds were hit with a surge in cash demands by investors, coupled with reduced inflows as economic uncertainty crippled markets. Consequently, many real estate funds, including CHYS, faced significant liquidity challenges leading to stalled projects. While the pandemic scenario was unforeseen, the experience highlights a great need for structured funds to develop better strategies for mitigating liquidity risks during future crisis.

- Need for Public and Investor Sensitization on structured products: The lack of widespread knowledge by the general public and potential investors on structured products created significant negative publicity for the fund which further impacted its optimal operations. Given this, there is greater need for continuous education of potential investors and general public to enhance understanding of structured products and SPVs specifically on the benefits, risks and operational framework in order to build trust and facilitate informed decision making.

- Need for stake holder education: on seeking administrative projection to restructure, the court ended up issuing liquidation orders of the fund, but also preserving, essentially crippling all the 10 projects, which made matters worse.

- The Alma Apartments in Ruaka (Cytonn Integrated Project LLP-SPV)

Formation and Purpose of the SPV

The Alma Apartments in Ruaka is a case example of a development done through the Cytonn Integrated Project LLP, a special purpose vehicle (SPV) formed to meet the rising demand for high-quality mixed-use units while delivering attractive returns to investors in the CHYS. The Cytonn Integrated Project LLP (Special Purpose Vehicle) is a limited partnership registered under the laws of the republic of Kenya and was created specifically to manage and own The Alma Project. The SPV operates with Standard Bank of Mauritius (SBM) as the custodian and Goal Advisory as the trustee who ensure proper oversight and accountability.

Overview of the Project

The Alma is a mixed-use comprehensive lifestyle development comprising of 477 units of 1,2 and 3-bed units’ typology. The project was designed to cater to the needs of middle-income families and young professionals, capitalizing on the growing demand for housing in Ruaka. The table shows the progress of the development as of 2025;

|

Type |

Feature |

|

Development Type |

Mixed Use Development |

|

Start Date |

April 2016 |

|

Completion Status |

Phase 1 – Completed Phase 2 – Completed Phase 3 – Completed Phase 4 – Still in progress |

|

No. of Blocks |

9 |

|

Number of Units |

477 |

|

Amenities |

Clubhouse, Swimming Pool, Gym, Kindergarten, Spa, retail centre etc. |

Source: Cytonn Research

Capital Raising Mechanism

The project’s funding was sourced through a combination of clients’ funds raised via CHYS and mezzanine financing. The Cytonn Integrated Project LLP -SPV functioned as a trading entity, meaning it generated income and value by holding the residential units within The Alma project and earning from the receivables tied to these units. These receivables are the payments made by buyers or tenants, which serve as a primary security for the investors of Cytonn High Yield Solutions (CHYS). Essentially, instead of relying on the value of undeveloped land, the SPV’S value is based on the payments from completed residential units that it holds as assets. The project was financed by several investors. The table below shows the Alma’s capital funding structure;

|

The Alma Capital Funding Structure |

|

|||

|

Security Ranking |

Proportion of Capital Funding (%) |

Type of Capital |

Description |

Number of Investors |

|

1st |

12.7% |

Bank Funding |

The 1st ranking source of funding which entails a registered charge amounting to Kshs 700 mn against the Alma Project. |

1 |

|

2nd |

3.6% |

The regulated Cytonn High Yield Fund (CHYF) |

Consists of secured funding from the CMA regulated CHYF, with a registered security interest amounting to Kshs 200 mn against the Alma project. |

20,000 |

|

3rd |

36.3% |

Presales contracts (Investors holding sales agreements) |

This is funding amounting to approximately Kshs 2.0 bn raised from the pre-sale of a total 477 home units at Alma secured through an equitable lien on the project via the purchase agreement |

477 |

|

3rd |

29.0% |

Mezzanine Funding from Cytonn High Yield Solution (CHYS) |

Entails approximately Kshs 1.6 bn of privately raised funding in Cytonn High Yield Solutions (CHYS) from 4,000 investors. |

4,000 |

|

4th |

18.4% |

Promoters and Equity Investors |

Involves approximately Kshs 1.0 bn funding raised from promoters and Equity Investors in the Alma project. |

250 |

Source: Cytonn Research

The above funding comes into the project through SPVs:

- Bank Funding comes into the development SPV - 1

- Regulated CHYF funding comes through the Trust SPV- 1

- Presales comes into the development SPV (same as a above)

- Mezzanine funding comes through two unregulated funding SPVs called CHYS and CPN – 2 SPVs

- Promoters come through various SPVS

- The project management SPV to do project management – coordinates project teams such as architect, engineers, contractor – 1 SPV

- The development management SPV to do development management - overall responsibility for the project – 1 SPV

- The facilities management SPV to manage the common areas facilities – 1 SPV

- Joint venture partners contribute the land through SPVs that are party to the JV, about 3 of them – 3 SPVs

From the above, one big real estate project alone requires about 10 SPVs each playing different roles. Multiple by 5 big projects, a modern-day real estate developer would require about 40 to 50 SPVs to execute 5 projects.

Project Execution and Return to Investors

Execution of the Alma was guided by detailed market research and an enhanced project management framework. Through the SPV, the Alma development has been able to successfully hand over 301 units across three phases, which then demonstrates the power of comprehensive market research. The SPV is still focused on securing financing to complete Phase 4. The Alma currently has a potential revenue of Kshs 2.5 bn from unsold units, representing a substantial future cash inflow. In addition, Kshs 211.3 mn remains collectible from units already sold but for which payments have not yet been completed. Combined, the total direct receivables from The Alma amount to Kshs 2.7 bn. In terms of transparency Cytonn Integrated Project LLP maintained rigorous reporting throughout the project’s lifecycle with regular updates provided to investors, covering progress on construction, sales performance, and financial metrics mitigating any potential risks.

Lessons Drawn from the Alma SPV:

- Stimulation of Capital Markets to Improve Access to Financing: Inadequate funding opportunities remains a significant challenge for development projects, often resulting in project delays or in some cases, project suspension. Without adequate funds, developers may struggle to commence or complete construction on time, resulting in extended project timelines which can frustrate buyers, erode investor confidence, and lead to reputational damage for the developer. As such, the government should work towards further stimulation of capital markets in order to improve access to financing for developers. This can be achieved through the establishment and effective utilization of specialized Collective Investment Schemes (CIS) and Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) known as Development REITs (DREITs) which can further increase availability of capital for development projects, while reducing reliance on traditional financing channels such as bank loans,

- Potential Delays in Construction Timelines: Unforeseen circumstances such as company governance issues, supply chain disruptions, or regulatory issues can cause construction timelines to be extended. This can impact both buyers and developers, as buyers will have to wait longer to take possession of their properties, and developers may face increased costs in order to complete the off-plan project,

- Off-plan Real Estate development: Off-plan Real Estate development and investing in Kenya offers a promising opportunity for both investors and developers aiming to capitalize on the country's rapidly growing property market. Investors can leverage the potential for significant returns and the advantage of purchasing properties at lower prices during the construction phase. Simultaneously, developers stand to benefit from pre-sales, which provide upfront funding and in ensuring a ready market for their properties ahead of project completion.

The Impact the Alma has had on the Real Estate Market

The Alma Apartments set a benchmark for mixed-use developments in satellite towns, showcasing the potential and demand for high-quality and relatively affordable housing to address Nairobi’s housing deficit. Its successful hand over of 301 units across three phases highlights the viability of alternative financing models, such as mezzanine debt and off-plan sales in driving real estate growth. The project’s focus on amenities and modern living standards has continued to influence market trends encouraging similar developments in Ruaka area and beyond.

Section VI: Benefits of SPVs in the Kenyan Financial Ecosystem

In the Kenyan financial ecosystem, SPVs have grown in prominence due to their role in structuring investments, enhancing financial inclusivity, and catalyzing economic growth. Their benefits include:

- Efficient Risk Management: SPVs enable businesses to isolate risks associated with specific projects. By compartmentalizing liabilities, SPVs protect the parent company's assets while ensuring targeted management of risks. For instance, in real estate development, SPVs are used to shield investors from project-specific risks.

- Facilitation of Large-Scale Infrastructure Projects: Kenya’s ambitious infrastructure projects, such as the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor and renewable energy projects, have leveraged SPVs to pool investments and manage project-specific finances. These projects, executed via SPVs, have boosted economic growth by creating jobs and improving connectivity.

- Attraction of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): SPVs provide a clear framework for investment, making it easier for foreign investors to participate in Kenya’s economy. The use of SPVs ensures transparency, encourages investor confidence, and fosters a conducive environment for capital inflows.

- Enhancement of Financial Inclusion: Through SPVs, marginalized sectors such as affordable housing and SME financing can access structured funding. The Kenyan government has established SPVs to drive affordable housing initiatives under the Big Four Agenda, thereby addressing housing deficits and contributing to social development.

- Diversification of Funding Sources: By pooling resources from multiple investors, SPVs enable funding for high-capital projects. This diversifies the financial ecosystem and reduces dependency on traditional banking systems. In Kenya, SPVs have played a pivotal role in real estate crowdfunding and asset-backed securities.

- Promotion of Capital Markets: SPVs issue securities such as bonds and sukuk (Islamic bonds), deepening Kenya's capital markets. For instance, green bonds issued through SPVs have financed sustainable development projects, aligning Kenya with global environmental goals and enhancing its international financial standing.

Section VII: Challenges Associated with Special Purpose Vehicles in Kenya

Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) in Kenya have gained importance in the financial and investment landscape as tools for isolating risks and facilitating structured finance transactions. However, the use and implementation of SPVs face several significant challenges and risks. Below are some of the key challenges facing SPVs in Kenya:

- Lack of Transparency: One critical issue with SPVs is the potential lack of transparency, which can undermine investor confidence. In Kenya, contributors to SPVs may not have full visibility into the nature of the assets held within the vehicle, their performance, or the associated risks. This lack of clarity can create mistrust, particularly in a market where financial literacy and regulatory enforcement are still evolving. For example, Kenyan investors might be unaware of the credit quality of underlying assets in an SPV or the specific mechanisms used to generate returns, increasing perceived risk.

- High Leverage: SPVs are often structured with high levels of leverage to enhance potential returns. However, this reliance on debt financing introduces significant risk, especially in a country like Kenya, where interest rates can be volatile. Poor debt management by SPV administrators can lead to substantial losses for investors. In addition, Kenya's financial markets are still maturing, and mechanisms for assessing and mitigating leverage risks are not always robust, further amplifying potential losses in the event of market shocks.

- High Complexity and Administrative Costs: Setting up and managing SPVs is inherently complex, involving detailed legal, regulatory, and administrative requirements. In Kenya, this complexity is compounded by unclear and sometimes burdensome regulatory processes. Entrepreneurs and investors must navigate costs related to maintaining separate records, preparing financial statements, and filing tax returns for SPVs. For instance, the lack of a streamlined process under the Companies Act or taxation framework adds administrative overhead, making SPVs less attractive for smaller businesses or investors.

- Conflicts of Interest: Conflicts of interest are another challenge, particularly when the sponsor of an SPV also acts as its manager. This dual role can lead to decisions that prioritize the sponsor's benefits over those of investors. In Kenya, where corporate governance standards are still developing, such conflicts can go unchecked, further discouraging participation in SPVs. For example, a sponsor might structure an SPV to offload high-risk assets from its balance sheet without adequately disclosing the risks to investors, leading to misaligned incentives and potential losses.

- Regulatory and Legal Framework Limitations: Kenya's regulatory framework for SPVs is still evolving, which can create uncertainty for investors and sponsors alike. Ambiguities in the Companies Act and Capital Markets Authority (CMA) regulations make it difficult to structure SPVs efficiently. This lack of regulatory clarity increases the likelihood of compliance breaches, which can lead to financial penalties or even legal disputes. Additionally, there is limited case law on SPVs in Kenya, making it challenging for parties to predict how courts will interpret disputes related to these entities.

- Limited Financial Literacy: In Kenya, a relatively low level of financial literacy among retail investors exacerbates the transparency challenge. Many investors may not fully understand the risks associated with SPVs or the legal and financial nuances of participating in such vehicles. This lack of knowledge creates a fertile ground for misinformation or even fraudulent schemes disguised as SPVs. For instance, cases of pyramid schemes masquerading as legitimate investment vehicles have eroded public trust in financial innovations, including SPVs.

- Market Fragmentation: Kenya's capital markets remain relatively small and fragmented, which limits the pool of potential investors for SPVs. Additionally, the lack of a secondary market for trading SPV interests reduces liquidity, making it harder for investors to exit their positions. This lack of liquidity is a significant deterrent, especially for institutional investors who prioritize flexibility in portfolio management.

Section VIII: Recommendations and Conclusion

To maximize the potential of SPVs in Kenya, various strategic actions can be undertaken by stakeholders, including the government, private sector, and investors. These include:

- Enhance Public and Stakeholder Education: The High Court in Insolvency Petition 063 of 2021, issued liquidation orders on its own motion primarily on the grounds that a fund not having the traditional banking charge on real estate projects and lending to related entities is akin to a fraud. Yet SPVs under one group typically lend to and borrow from each other in the ordinary cause of business and the securities among them are not the traditional securities that banks provide.

- Enhance Regulatory Framework- Simplifying the formation and registration process, establishing clear guidelines, and enforcing strong investor protection measures are key steps to create a more favorable environment for SPVs. Additionally, businesses must strictly adhere to global accounting standards like IFRS and GAAP for accurate and transparent financial reporting. This ensures that SPVs operate within legal frameworks and helps maintain investor confidence.

- Facilitate Access to Capital- The costs associated with establishing and maintaining SPVs can be prohibitive, particularly for smaller projects. Many SPVs struggle to secure funding due to stringent lending requirements or lack of investor confidence and since SPVs operate as separate entities, they often lack the creditworthiness of their sponsor companies, making it challenging to secure funding at favorable terms.

- Strengthen Governance and Transparency- SPVs must have well-defined governance frameworks that specify roles, responsibilities, and decision-making processes. Independent directors and transparent reporting can significantly reduce the risk of mismanagement and misuse. Additionally, develop comprehensive internal control systems to ensure that all financial transactions are accurately reported, preventing the concealment of liabilities or financial misstatements and conduct regular Auditing.

- Risk Management and Operational Efficiency- Conduct comprehensive risk assessments when designing and structuring SPVs. This includes identifying potential financial, operational, and legal risks to better manage and mitigate them. Clearly define the SPV’s purpose and scope to avoid mission creep, which can lead to inefficiencies or unintended liabilities. The SPV should focus on specific objectives such as asset holding, project financing, or risk isolation.

- Simplify and Streamline Financial Reporting- SPVs introduce additional complexity into accounting and financial reporting due to their distinct legal and financial structures. If a parent company control over an SPV or assumes its risks, accounting standards requires the consolidation of the SPV's financial statements with those of the parent company. However, the process can be intricate, requiring detailed assessments of control, risks, and benefits associated with the SPV. Any improper handling, misrepresentation, or omission of SPV financials can lead to serious consequences, including regulatory penalties, damaged investor trust, and reputational harm. Businesses must prioritize accuracy, compliance, and transparency in reporting SPV financials to mitigate these risks and uphold stakeholder confidence.

- Facilitate Capacity Building- Provide training and resources for regulators, financial institutions, and corporate entities to understand SPV complexities, ensuring informed decision-making and effective oversight.

SPVs are independent entities established to isolate financial risks, facilitate capital raising, and manage assets efficiently. They offer advantages such as tax benefits, improved access to funding, and protection for parent companies. By isolating risks, facilitating structured investments, and fostering public-private collaborations, SPVs contribute to the country’s economic growth and development. They are essential to raising capital that is needed to addressing big projects such as housing and infrastructure and should be natured to bring capital and impact to these sectors. However, their success hinges on strong governance, stakeholder awareness, regulatory compliance, and transparency to build investor confidence and sustain long-term benefits.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the writers where particulars are not warranted. This publication, which is in compliance with Section 2 of the Capital Markets Authority Act Cap 485A, is meant for general information only and is not a warranty, representation, advice or solicitation of any nature. Readers are advised in all circumstances to seek the advice of a registered investment advisor.