May 10, 2020

On April 25th 2020, President Uhuru Kenyatta assented the amendments to the Tax Act 2020, one of which was to the Retirement Benefits Act allowing pensioners to use their savings to purchase a residential house and withdrawal taxation rate; this is in line with the Big 4 agenda to promote housing. Following this amendment, the Retirement Benefits Authority drafted regulations aimed at governing the new provision. As such, this week, we seek to enlighten the market on the changes made in the Retirement Benefits Authority (RBA) Regulations, what the changes mean for retirement schemes and the pensions industry going forward and our take on the adequacy and effectiveness of the proposed regulations.

But before we continue, we must commend RBA for their responsiveness: the President assented to the Tax Act on April 25th 2020 and in less than a month, we already have the draft regulations for discussion on how they impact the President’s Big 4 housing agenda. This responsiveness is in stack contrast to the Finance Act 2019, which the President assented to on November 2019, and, inter alia, provided that “Deposits in a registered home ownership savings plan shall be invested in accordance with… regulations issued by the Capital Markets Authority;” The home ownership amendment was to expand homeownership savings instruments to include capital markets instruments, in addition to bank savings, so that Kenyans saving for homes can earn higher capital markets returns on their savings for home ownership. If you save through a bank, the return is about 5%, compared to saving through a capital markets instrument where the return is about 10%. However, it has been 7 months since the presidential assent and the Capital Markets Authority, CMA, is yet to issue draft regulations. Prospective homeowners and affordable housing developers are left awaiting the draft regulations from CMA to operationalize the capital markets homeownership savings plan that the President assented to on November 7th 2019.

Back to the RBA proposed regulations, we review the topic in five sections as follows:

- Introduction: Role of the RBA and Reasons for the Recent Amendments to RBA Regulations,

- Changes in the RBA Regulations,

- Our Take on the Proposed Regulations,

- Case Study – Singapore’s Central Provident Fund, and,

Section 1: Introduction: Role of the RBA and Reasons for the Recent Amendments to RBA Regulations

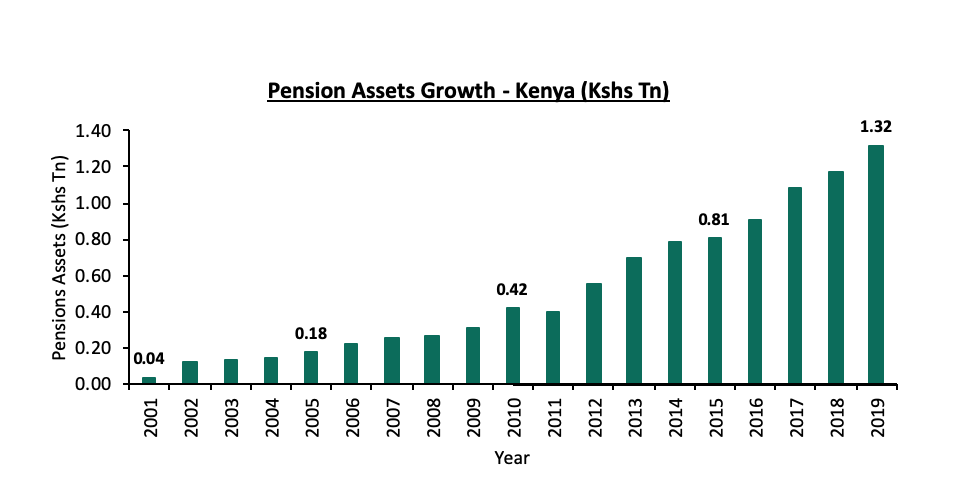

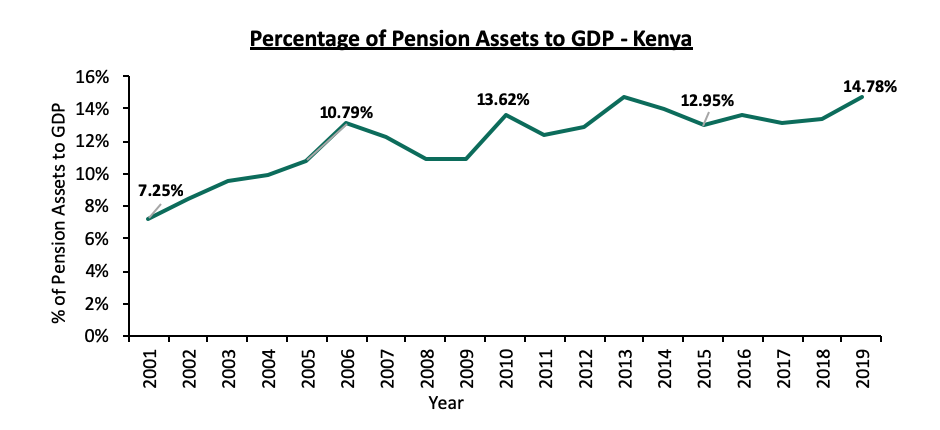

The Retirement Benefits Authority is the government body established under the terms of the Retirement Benefits Act 1997 tasked with the regulation, supervision and promotion of retirement benefits schemes in Kenya. The Authority is also in charge of protecting the interests of members and sponsors of the retirement benefits sector. The Retirement Benefits Authority Regulations serve as subsidiary legislations to the Act and contain guidelines for the treatment of members’ benefits, investments, withdrawals, reports and restriction on the use of scheme funds. The retirement industry plays a big role in the economy of Kenya with assets worth Kshs 1.32 tn as at December 2019 and averaged 13.55% of the country’s GDP over the last 10-years.

The industry has witnessed significant growth increasing by a 9-year CAGR of 17.6%, from 0.7 mn registered members in 2010 to 3.01 mn members as of December 2019, according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) FinAccess Report 2019. Despite the growth, many Kenyans still suffer from low pension adequacy upon retirement; this is due to poor savings culture whereby many employees withdraw their allowable portion of their retirement savings when moving from one employer to another.

Through the Tax Act 2020, the government introduced various economic measures aimed at alleviating the housing deficit in Kenya as well as easing the effects of the Corona disease on household incomes. This was achieved through an amendment to Section 38 of the Retirement Benefits Act to allow the use of retirement savings to purchase a residential house in a bid to improve home ownership in Kenya. The government has made it possible for citizens in registered retirement benefits schemes to use a portion of their retirement benefits to purchase a residential house. This is in addition to the previously existing law that allowed retirement schemes’ members to allocate up to 60% of their benefits towards securing a mortgage loan.However, the mortgage was never really used because banks preferred to have the actual house as security rather than the pension savings.

Section 2: Changes in the RBA Regulations

The law providing for reduction of the tax rates upon withdrawal and the addition of use of retirement savings to purchase a house were assented to by the President on April 25th 2020. The regulations however to govern the purchase of house are proposals by the Cabinet Secretary and are yet to be gazetted. Below we list the proposed changes relating to purchase of housing:

- The proportion available for the purchase of a residential house at the time of the application shall be the lower of 40% of the member’s accumulated benefit subject to a maximum of Kshs 7.0 million or the purchase price of the house. This means that a worker who wishes to buy a residential house can do so directly from their pension utilizing up to 40% of their accumulated benefits; the maximum however they can use is Kshs 7 million and the amount they use should not exceed the buying price of the house. Accumulated benefit here refers to the total pension contribution over the years plus interest earned,

- Addition of paragraph (c) to the definition of institution to read:

- a bank, mortgage or financial institution licensed under the Banking Act (Cap. 488), a building society licensed under the Building Societies Act (Cap. 489), a microfinance institution established under the Microfinance Act, 2006 (No. 19 of 2006) the National Housing Corporation; or

- any other institution, including an issuer of a tenant purchase arrangement that is specifically approved by the Authority for the purpose of providing a facility; or

- an institution or projects approved by the ministry in charge of matters relating to housing or licensed under the SACCO Societies Act, Insurance Act or a scheme with residential houses for sale;

This means that on top of the already existing institutions qualified by (a) and (b), scheme members may purchase a house from SACCOs, Insurance companies, and retirement schemes that have built or own residential houses for sale. Members can also buy a house from the Ministry of Transport, Infrastructure, Housing & Urban Development-approved institutions and projects. An example of this is the Boma Yangu Affordable Housing Programme.

- Amendment of the definition of the word “house” to be a residential house,

- A member can utilize either of the option to be issued with a guarantee to secure a mortgage loan or to utilize their benefits to purchase a house but not both,

- A member of a scheme can only be allowed to utilize their funds to purchase a house once,

- A member who has attained the normal retirement age or is already receiving a pension from the scheme is not eligible to apply for the purchase of a house from their benefits

- The application of a member to use part of his retirement savings to purchase a house shall not take more than 60-days in consideration before a decision is made, and,

- Every scheme shall provide the minimum requirements to be met by members, for an application submitted under these Regulations.

Section 3: Our Take on the Proposed Regulations

The new law to allow members to purchase homes through their pension savings is welcome as it provides an incentive for workers to save in retirement benefits schemes as well as boost one of the Government’s Big Four Agenda, which aims to improve homeownership rates by enhancing the diversification of sources of funds to be used in the purchasing of residential homes by Kenyans.

We, however, find that there is a need for further six clarifications as follows:

- For the regulation to be appropriately descriptive, we suggest it is called the “The Retirement Benefits (Mortgage Loans and Residential Purchases) Regulations”, so that it is clear the regulations are equally about both getting mortgages and purchasing residential units. Leaving the name of the regulation to be about mortgages only makes it look like it is about mortgages, yet it is equally about mortgages as it is about residential purchases,

- Definition of “institution” should be clear in terms of the purpose of the institution because we have two different institutions:

- Institutions to issue mortgage loans and facilities secured by retirement benefits; for example banks, mortgage companies, and,

- Institutions to avail residential units for purchases, such as real estate developers and vendors.

These two are totally different institutions and should be separated in the definitions. We should have lending institutions and real estate vendors/institutions. To say that the residential units being purchased have to be from an institution and then describe an institution as a bank seems bizarre since they typically don’t sell real estate, and this kind of confused definition could easily attract litigation from the industry since statutes and regulations ought to be clear,

- Arising from (ii) above, the way the regulations are written, they are discriminative as to what type of a residential unit a member can buy. They are very punitive to real estate developers because the funds cannot be used to purchase a residential unit unless the unit is being sold by a SACCO, an insurance company, pension fund or a project approved by the ministry of housing. This excludes the entire real estate developer world - large, small and individual developers. The restriction also exposes members to the risk of schemes undertaking development, which is not their forte, as can be demonstrated by schemes that have recently gone into the development and ended up with loss-making projects for the scheme. Members should be able to purchase suitable real estate from vendors of their choice,

- Just like in the case of a mortgage to buy a house is allowed at 60% of member benefits, the amount to buy a house should also be 60% of member benefits, the limitation to 40% for the sake of buying a residential unit, as opposed to 60% when borrowing seems skewed towards favoring borrowing rather than buying,

- The limitation to an absolute figure of seven million also seems discriminatory; once the percentage of accessible benefits has been determined, whether 40% or 60%, then we should let the percentage determine the absolute figure, similar to the way Regulation 11 currently limits assignment of benefits to 60%, but has no absolute limit. This limitation again appears to be favoring mortgages as opposed to housing purchases and could be deemed discriminatory,

- Proposed Regulation 15 (5), we propose to add section (e) an ability for the authority to waive the encumbrance to allow for future flexibility for unforeseen circumstances. Just keeping the occurrences to (a) through (d) is restrictive. For example, it is possible that the market may over time develop reverse mortgage, where a retiree begins to get monthly income against their residential property upon retirement and then upon death they would transfer the property to the reverse mortgage provider. There is a need to leave a window open for product development with the approval of the Authority.

As currently put forward by the Cabinet Secretary, Regulation 15 (5) states that “Trustees of the scheme shall ensure and/or cause the title to the residential house to be encumbered to restrict transfer to any person. The restriction shall stand until there is an occurrence of any of the following events;

- A member has retired from service on early retirement grounds, or has attained age sixty or the normal retirement age of the scheme whichever is earlier;

- Death of a member;

- Member becomes incapacitated due to ill health or permanent disability to the extent that it would occasion his retirement;

- f the member is emigrating from Kenya to another country without the intention of returning to reside in Kenya and approval has been granted by the Authority; “

In summary, from the title of the regulation to the allowable percentages, the regulation seems more inclined to members taking mortgages rather than outrightly purchasing residential units, it is not clear what is the policy intention of this inclination, if anything it just saddles members with debt rather than allow them outright purchases of residences.

Section 4: Case Study – Singapore’s Central Provident Fund

In this section, we take a look at a country that allows retirement savings to be used to purchase residential houses. We focus on the pension system in Singapore, a country which has a high integration between housing and pension policies. The Central Provident Fund (CPF) – the statutory scheme – has been integrated as one of the three key pillars of housing policy in the country; the other two are Lands Acquisition Act and the Housing Development Board.

The Central Provident Fund Board is the statutory authority that administers the country’s mandatory and comprehensive pension scheme, Central Provident Fund. This is similar to NSSF here in Kenya. The contribution rates to CPF are from the employee 20% of their income and from the employer, 17% of the employee’s income (these contribution rates may vary with age). Mandatory CPF contributions are tax-exempt for both the employer and employee. The same applies to pre-retirement and retirement withdrawals from the three accounts discussed below. Both the employer and employee may make additional voluntary contributions to the CPF, but these contributions are not subject to tax breaks.

The contributions are distributed to 3 accounts:

- Ordinary Account – Funds in this account can be used for housing insurance, education and other approved usages,

- Special Account – The funds here are purely for old-age and investing in retirement-related products

- MediSave Account – Funds accumulating in this account are for approved hospitalization and medical insurance expenses.

There is an additional account automatically created when one reaches the age of 55 years.

- Retirement Account – This is automatically created upon attaining the age of 55 years old which is the lowest age that one can access their pension savings. Upon reaching 55 years old, the Ordinary and Special Account merge to form the Retirement Account and the money will be used as retirement income.

Once contributions are remitted, the funds are divided into the three accounts as follows: (The amounts here refer to the percentage of your pay)

|

Age |

CPF allocation for Ordinary Account |

CPF allocation for Special Account |

CPF allocation for MediSave Account |

|

Up to 35 years old |

23.0% |

6.0% |

8.0% |

|

35 to 45 years old |

21.0% |

7.0% |

9.0% |

|

45 to 50 years old |

19.0% |

8.0% |

10.0% |

|

50 to 55 years old |

15.0% |

11.5% |

10.5% |

|

55 to 60 years old |

12.0% |

3.5% |

10.5% |

|

60 to 65 years old |

3.5% |

2.5% |

10.5% |

|

Above 65 years old |

1.0% |

1.0% |

10.5% |

The funds allocated in the Ordinary Account may be used to cater for property expenses in any of the following ways:

- Pay the purchase price of a new house

- Repay a housing loan fully or partially for an already existing loan

- Repay the construction loan instruments or loan instruments take to buy land for construction

- Pay stamp duty, legal costs, survey fees and any other costs incurred in the purchase of private property

CPF savings can only be used if you are buying a House Development house or private property with a remaining lease of at least 30 years, provided one’s age plus the remaining lease is at least 80 years. All properties in Singapore have a renewable lease of 99 years old. The total CPF usage by the household is capped at a percentage of the property purchase price or the value of the property at the time of purchase, whichever is lower.

Also, there are no limits to withdraw CPF savings to buy a new flat from the Housing Development Board (HDB) which is a Singapore's public housing authority that plans and develops housing estates.

The scheme has proven successful, with Singapore registering one of the highest home ownership rates globally at 90.3% with 80% of this being public housing. The CPF aims to make members have enough retirement savings to meet their basic expenses in retirement, have a property that is fully paid up when they retire and have adequate savings to cover their medical expenses in old age.

Kenya can borrow a few lessons from the above case study:

- Increase limits of funds available to purchase a house: CPF allows 23% out of the 37% total contribution to be utilized for purchase a house; this translates to 62% of a member’s total contribution. Additionally, there is no upper limit as we have in the proposed amendment of Kshs 7 million.

If the logic is to increase house ownership in Kenya then the Ministry should consider not inhibiting too much the allowable portion for their agenda as that would be shooting their foot,

- Lessening restrictions on qualified real estate providers: Kenya could borrow from the limit restrictions Singapore applies. For CPF, there is no limit for usage of the retirement savings to purchase a house developed by their Housing Development Board – you can use 100% of your pension to purchase a government developed house. The limit of 62% of your pension applies to all the other real estate developers. Kenya could apply the same by putting no restrictions on purchases of Government-built houses while the limit restriction applies to the rest of the market with no inhibitions (in terms of banks or SACCOs),

Section 5: Conclusion

The current regulations, as proposed, need to be reviewed in three key respects;

- First, proposed regulations effectively exclude purchasing units from real estate developers,

- Second, the definition of institutions whose units qualify to be purchased using pension funds is confusing, since the regulations do not differentiate between financing institutions and developer institutions,

- Finally, the percentage allowed for either mortgage access or outright purchase access need to be the same,

If the above three key issues are not addressed, the proposed regulations will effectively be a cosmetic regulatory piece that cunningly defeats what was decisive legislation to promote housing purchase.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the writers where particulars are not warranted. This publication is meant for general information only and is not a warranty, representation, advice or solicitation of any nature. Readers are advised in all circumstances to seek the advice of a registered investment advisor.