Rate Cap Review Should Focus More on Stimulating Capital Markets, & Cytonn Weekly #19/2018

By Cytonn Research Team, May 13, 2018

Executive Summary

Fixed Income

T-bills were oversubscribed during the week, with the subscription rate coming in at 165.7%, up from 136.8% the previous week. Yields on the 91, 182 and 364-day papers remained unchanged at 8.0%, 10.3% and 11.1%, respectively. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) released their Regional Economic Outlook report for Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) dated April 2018, with a focus on domestic revenue mobilization and private investment, projecting SSA GDP growth at 3.4% for 2018, up from 2.8% in 2017;

Equities

During the week, the equities market was on a downward trend with NASI, NSE 20 and NSE 25 losing 1.5%, 2.6% and 0.8%, respectively. For the last twelve-months (LTM), NASI, NSE 20 and NSE 25 have gained 28.4%, 12.7% and 28.5%, respectively. Mortgage financier HF Group borrowed Kshs 800.0 mn in short-term loans last year from NIC Group and Co-operative Bank, which were to be serviced at 14.0% and 13.0%, respectively, in order to meet their maturing bond obligations. Commercial banks will be allowed to charge borrowers based on their risk profiles in a new proposed amendment to the law capping interest rates;

Private Equity

During the week, we witnessed private equity activity in the Kenyan financial services sector and the global hospitality sector. Sanlam Kenya, a listed Kenyan insurance firm, stated in its annual report that it had invested an additional Kshs 121.7 mn in Sanlam General, raising its total investment in the subsidiary to Kshs 1.0 bn. AccorHotels, a French multinational hotel group, signed an agreement with Mövenpick Holding and Kingdom Holding to acquire a 100.0% stake of Mövenpick Hotels & Resorts, a hotel management company headquartered in Switzerland, for 560.0 mn Swiss Francs (USD 558.3 mn);

Real Estate

During the week, the real estate sector recorded increased investor interest evidenced by the announcement by Erdemann Property Ltd, a Nairobi-based property development company, announcing their plan to construct eight 34-storey blocks in Ngara Estate. In the retail sector, troubled retail chain Nakumatt Holdings closed its City Hall and Galleria Mall branches, owing to its accumulated unpaid dues;

Focus of the Week

This week we revisit the interest rate cap following the recent announcement by the Treasury that a draft proposal to address credit management in the economy, which will eventually lead to the elimination of the law capping interest rates, will be tabled in Parliament. The repeal of the interest rate cap and the Government’s fiscal consolidation were part of the agreement the Treasury made with the IMF, in order to be granted a six months’ extension for the USD 1.5 bn stand-by credit and precautionary facility. We therefore look at what led to the enactment of the interest rate cap, the effects it has had, and the way forward for the law, including our view of what should be included in the legislative review. We are of the view that in addition to focusing on the rate cap review, it is important the legislation also stimulates capital markets funding in order to reduce overreliance on banks for loans.

- Cytonn Investments Management Plc and Cytonn Cash Management Solutions LLP shall hold their Annual General Meeting for the year ended December 2017, on Friday, 18th May 2018, at 7:30 am at Radisson Blu Hotel, Upperhill. See the agenda here

- Cytonn Diaspora hosted an investment forum in London on the 4th of May 2018, for Kenyans in the UK interested in investing back in Kenya. See Event Note

- Cytonn Real Estate held its quarterly FAs & IFAs Awards for the 1st Quarter of 2018, awarding top performing Independent and Tied Real Estate Financial Advisors (REFAs). During the event, Mex Osoro, Cytonn’s Senior Distribution Manager, mentioned that the team had been able to achieve sales of Kshs 1.7 bn during Q1’2018. See Event Note

- The latest Issue of Sharp Cents, a quarterly publication by Cytonn Investments Management Plc is out. You can download the online version here

- We continue to hold weekly workshops and site visits on how to build wealth through real estate investments. The weekly workshops and site visits target both investors looking to invest in real estate directly and those interested in high yield investment products to familiarize themselves with how we support our high yields. Watch progress videos and pictures of The Alma, Amara Ridge, The Ridge, and Taraji Heights. Key to note is that our cost of capital is priced off the loan markets, where all-in pricing ranges from 16.0% to 20.0%, and our yield on real estate developments ranges from 23.0% to 25.0%, hence our top-line gross spread is about 6.0%. If interested in attending the site visits, kindly register here

- We continue to see very strong interest in our weekly Private Wealth Management Training (largely covering financial planning and structured products). The training is at no cost and is open only to pre-screened participants. We also continue to see institutions and investment groups interested in the trainings for their teams. The Wealth Management Trainings are run by the Cytonn Foundation under its financial literacy pillar. If interested in our Private Wealth Management Training for your employees or investment group please get in touch with us through wmt@cytonn.com. To view the Wealth Management Training topics, click here

- For recent news about the company, see our news section here

- We have 10 investment-ready projects, offering attractive development and buyer targeted returns of around 23.0% to 25.0% p.a. See further details here: Summary of Investment-Ready Projects

- We continue to beef up the team with ongoing hires for: Quality Control and Assurance Manager & Associate, Sales & Marketing Manager, Procurement Manager, Relationship Manager – Corporate Affairs, Portfolio Manager and Investments Associate – Public Markets, among others. Visit the Careers section at Cytonn’s website to apply

T-bills were oversubscribed during the week, with the subscription rate coming in at 165.7%, up from 136.8%, the previous week. The subscription rates for the 91, 182 and 364-day papers came in at 120.8%, 150.8%, and 198.4% compared to 122.9%, 124.2%, and 155.1%, respectively, the previous week. Yields on the 91, 182 and 364-day papers remained unchanged at 8.0%, 10.3% and 11.1%, respectively. The acceptance rate for T-bills improved to 91.2% from 81.1%, the previous week, with the government accepting a total of Kshs 36.3 bn of the Kshs 39.8 bn worth of bids received, against the Kshs 24.0 bn on offer. The government is currently 33.0% ahead of its pro-rated domestic borrowing target for the current fiscal year, having borrowed Kshs 342.5 bn, against a target of Kshs 257.5 bn (assuming a pro-rated borrowing target throughout the financial year of Kshs 297.6 bn).

For the month of May 2018, the Kenyan Government has issued a new 15-year Treasury bond (FXD 1/2018/15) with the coupon set at 12.7%, in a bid to raise Kshs 40.0 bn for budgetary support. The sale period ends on 22nd May, and we shall give our view on a bidding range in next week’s report.

Liquidity levels declined in the money market as indicated by the increase in the average interbank rate to 5.0%, from 4.8% recorded the previous week, following tax remittances by banks. There was an increase in the average volumes traded in the interbank market by 4.7% to Kshs 15.5 bn, from Kshs 14.8 bn the previous week.

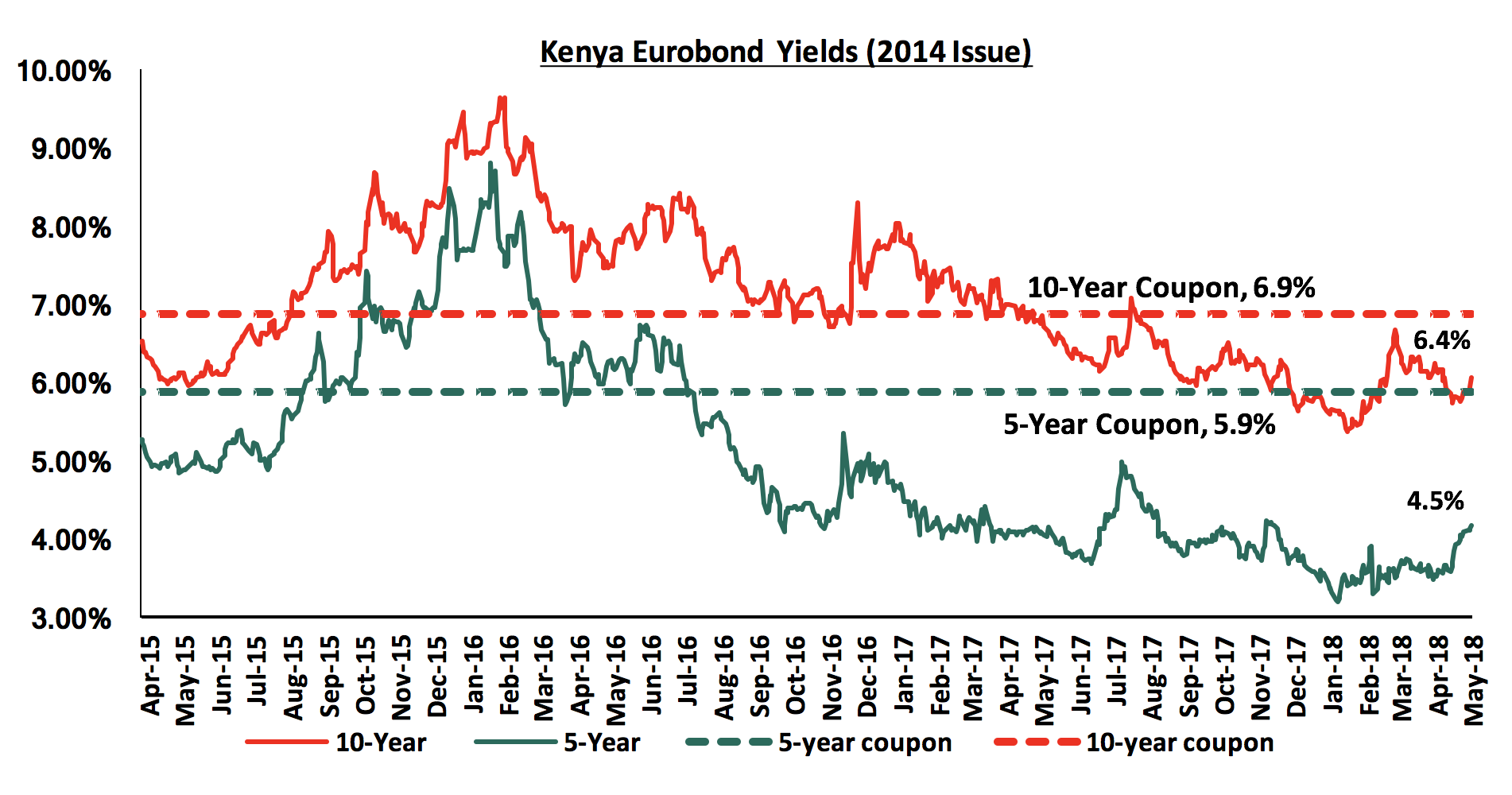

According to Bloomberg, the yield on the 5-year Eurobond issued in June 2014 increased by 10 bps to 4.5% from 4.4%, the previous week, while the yield on the 10-year Eurobond remained unchanged at 6.4%. Since the mid-January 2016 peak, yields on the Kenya Eurobonds have declined by 4.3% points and 3.2% points for the 5-year and 10-year Eurobonds, respectively, due to the relatively stable macroeconomic conditions in the country. Key to note is that these bonds currently have 1.1 and 6.1-years to maturity for the 5-year and 10-year bonds, respectively.

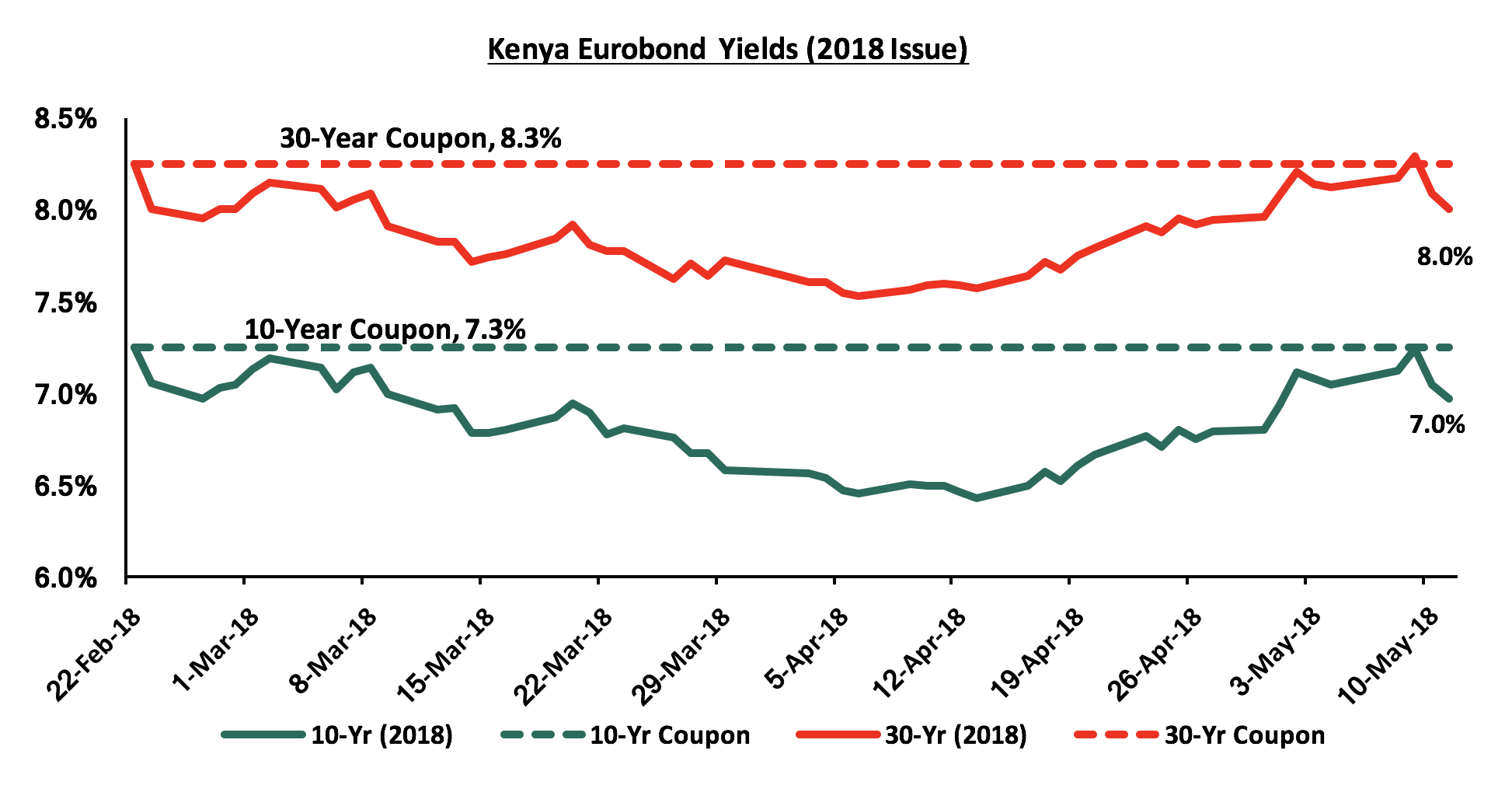

For the February 2018 Eurobond issue, during the week, the yield on the 10-year Eurobond remained unchanged at 7.0%, while the yield on the 30-year Eurobond declined by 10 bps to 8.0%, from 8.1%, the previous week. Since the issue date, yields on the 10-year and 30-year Eurobonds have both declined by 0.3% points each, indicating foreign investor confidence in Kenya’s macroeconomic prospects.

During the week, the Kenya Shilling depreciated by 0.2% against the US Dollar to close at Kshs 100.4, from Kshs 100.2 the previous week, as a result of increased dollar demand from oil importers. On a YTD basis, the shilling has gained 2.7% against the USD. In our view, the shilling should remain relatively stable against the dollar in the short term, supported by:

- Stronger horticulture export inflows driven by increasing production and improving global prices,

- Improving diaspora remittances, which increased by 50.6% to USD 222.2 mn in March 2018 from USD 147.5 mn in March 2017, attributed to (i) increased uptake of financial products by the diaspora due to financial services firms, particularly banks, targeting the diaspora, and (ii) new partnerships between international money remittance providers and local commercial banks making the process more convenient. Key to note is that in 2017, diaspora remittances became the largest foreign exchange earner at Kshs 202.9 bn, exceeding tea exports and tourism receipts, which earned Kshs 119.9 bn and Kshs 147.2 bn, respectively,

- High forex reserves, currently at USD 9.1 bn (equivalent to 6.1 months of import cover), which is a decline from USD 9.5 bn (equivalent to 6.4 months of import cover) as at 26th April, attributed to repayment of the outstanding balance of the matured USD 750 mn syndicated loan taken in October 2015, and,

- The USD 1.5 bn stand-by credit and precautionary facility by the IMF, still available until September 2018, after which a new facility will be discussed.

From the Treasury’s programme-based budget of the National Government of Kenya for the year ending 30th June 2019, loan repayments to China are set to increase by 129.0% in the fiscal year 2019/20, to an estimated Kshs 82.9 bn from an estimated Kshs 36.2 bn in the financial year 2018/19, as the grace period that had been extended to Kenya for the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) loan comes to an end. Principal payments for the loan to the Kenyan Government from the Export-Import Bank of China of USD 3.2 bn, to build Phase I of the SGR, are set to increase by 36.1% to Kshs 8.3 bn in financial year 2018/19, and Kshs 34.8 bn in financial year 2019/20, from Kshs 6.1 bn this financial year as the grace period extended comes to an end. The loan comprised of a (i) USD 1.6 bn semi-concessional loan at an interest rate of 2.0%, paid over 20-years, with a grace period of 7-years, and (ii) USD 1.6 bn commercial loan at an interest rate of 3.6% above the prevailing 6 month-LIBOR, paid over 15-years, with a grace period of 5-years. This comes at a time when the World Bank, in its Pulse Report, raised concerns over the rising public debt levels in Sub-Saharan Africa, citing the composition of debt has changed, as countries have shifted away from traditional concessional sources of financing toward more market-based ones. Higher debt burdens and the increasing exposure to market risks raise concerns about debt sustainability. As discussed in our topical on Kenya’s Public Debt, Should We Be Concerned?, we maintain that the government should implement decisive policies to curtail the growth of Kenya’s public debt burden and reduce the risk of the country joining the list of debt defaulters.

During the week, the IMF released their Regional Economic Outlook report for Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) dated April 2018, with a focus on domestic revenue mobilization and private investment. The key take-outs from the report were:

- GDP growth in SSA is projected to come in at 3.4% in 2018, up from 2.8% in 2017, supported by higher commodity prices, and improved capital markets access,

- The average current account deficit in SSA is estimated to have narrowed to 2.6% of GDP in 2017, from 4.1% in 2016. The improvement was due to an increase in international receipts in about half of the region’s economies. For large oil exporters, external balances improved due to higher oil production, improvement in oil prices, and reduced imports with the current account deficit in the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC) declining to 4.3% of GDP in 2017, from 13.8% of GDP in 2016. In non-resource intensive countries, the current account deficits remained high in 2017, due to a combination of low exports, high capital goods imports, high food and fuel imports, and increased imports related to public infrastructure projects, and,

- Regional annual inflation in SSA fell to just over 10.0% in 2017, from 12.5% in 2016, and is expected to fall further in 2018, driven by declining food prices due to improved weather conditions.

The report points to an improved operating environment in SSA with (i) projected higher GDP growth in 2018 of 3.4%, compared to 2.8% in 2017, (ii) the average current account deficit narrowing to 2.6% of GDP in 2017, from 4.1% in 2016, and (iii) average annual inflation declining to 10.0% in 2017 from 12.5% in 2016, and expected to fall further in 2018. The key concern, however, remains the rising debt burden, as public debt continued to rise in 2017, with about 40.0% of low-income developing countries in the region being in debt distress or at a high risk of debt distress, and the median level of public debt in SSA exceeding 50.0% of GDP. With the rise in debt, interest payments have also been on the rise, with the median interest payments-to-revenue ratio close to 10.0%, up from 5.0% in the period between 2013 and 2017.

The IMF, however, maintained their 2018 GDP projection for Kenya at 5.5%, bringing the average of projections as at Q2’2018 to 5.5%, as shown in the table below. We shall continue to update this table as these organizations release their updated 2018 projections.

|

Kenya 2018 Annual GDP Growth Outlook |

|||

|

No. |

Organization |

Q1'2018 |

Q2'2018 |

|

1 |

Central Bank of Kenya |

6.2% |

|

|

2 |

Kenya National Treasury |

5.8% |

|

|

3 |

Oxford Economics |

5.7% |

|

|

4 |

African Development Bank (AfDB) |

5.6% |

|

|

5 |

Stanbic Bank |

5.6% |

5.6% |

|

6 |

Citibank |

5.6% |

|

|

7 |

International Monetary Fund (IMF) |

5.5% |

5.5% |

|

8 |

World Bank |

5.5% |

5.5% |

|

9 |

Fitch Ratings |

5.5% |

|

|

10 |

Barclays Africa Group Limited |

5.5% |

|

|

11 |

Cytonn Investments Management Plc |

5.4% |

5.5% |

|

12 |

Focus Economics |

5.3% |

|

|

13 |

BMI Research |

5.3% |

5.2% |

|

14 |

Standard Chartered |

4.6% |

|

|

|

Average |

5.5% |

5.5% |

Rates in the fixed income market have remained stable as the government rejects expensive bids. The government is under no pressure to borrow for this fiscal year as: (i) they are currently ahead of their domestic borrowing target by 33.0%, (ii) they have met 72.9% of their total foreign borrowing target and 84.2% of their pro-rated target for the current fiscal year, and (iii) the KRA is not significantly behind target in revenue collection. Therefore, we expect interest rates to remain stable. With the expectation of a relatively stable interest rate environment, our view is that investors should be biased towards medium to long-term fixed income instruments. We are currently revising our view on fixed income investments and shall include a comprehensive analysis of this in next week’s report.

During the week, the equities market was on a downward trend with NASI, NSE 20 and NSE 25 losing 1.5%, 2.6% and 0.8%, respectively. This takes the YTD performance of NASI, NSE 20 and NSE 25 to 4.1%, (3.0%) and 5.2%, respectively. This week’s performance was driven by declines in BAT, Barclays Bank Limited and Safaricom, which declined by 7.7%, 3.3%, and 2.6%, respectively. For the last twelve months (LTM), NASI, NSE 20 and NSE 25 have gained 28.4%, 12.7% and 28.5%, respectively.

Equities turnover increased by 11.2% to USD 47.7 mn from USD 42.9 mn the previous week. We expect the market to remain resilient this year supported by positive investor sentiment, as investors take advantage of the attractive stock valuations in select counters.

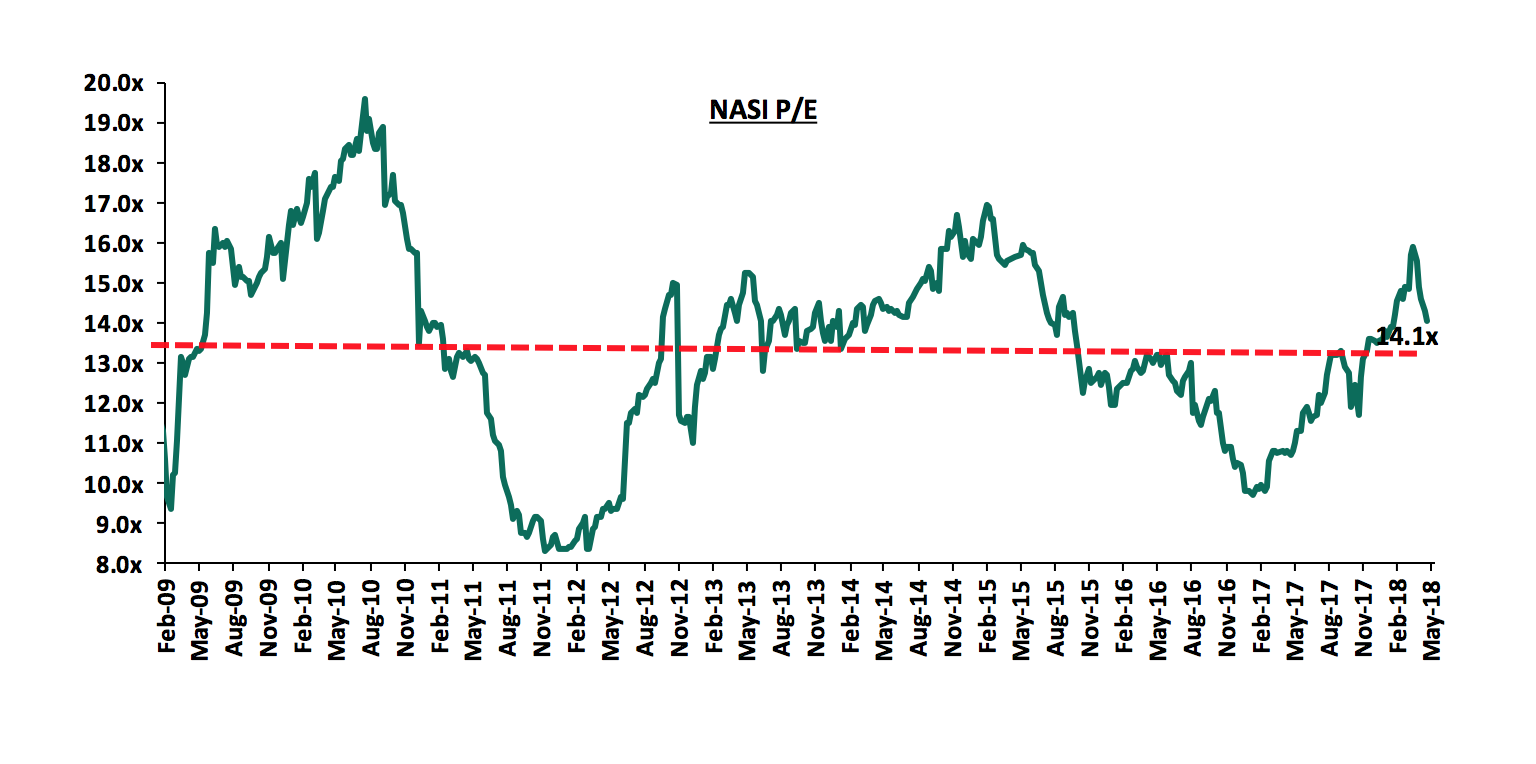

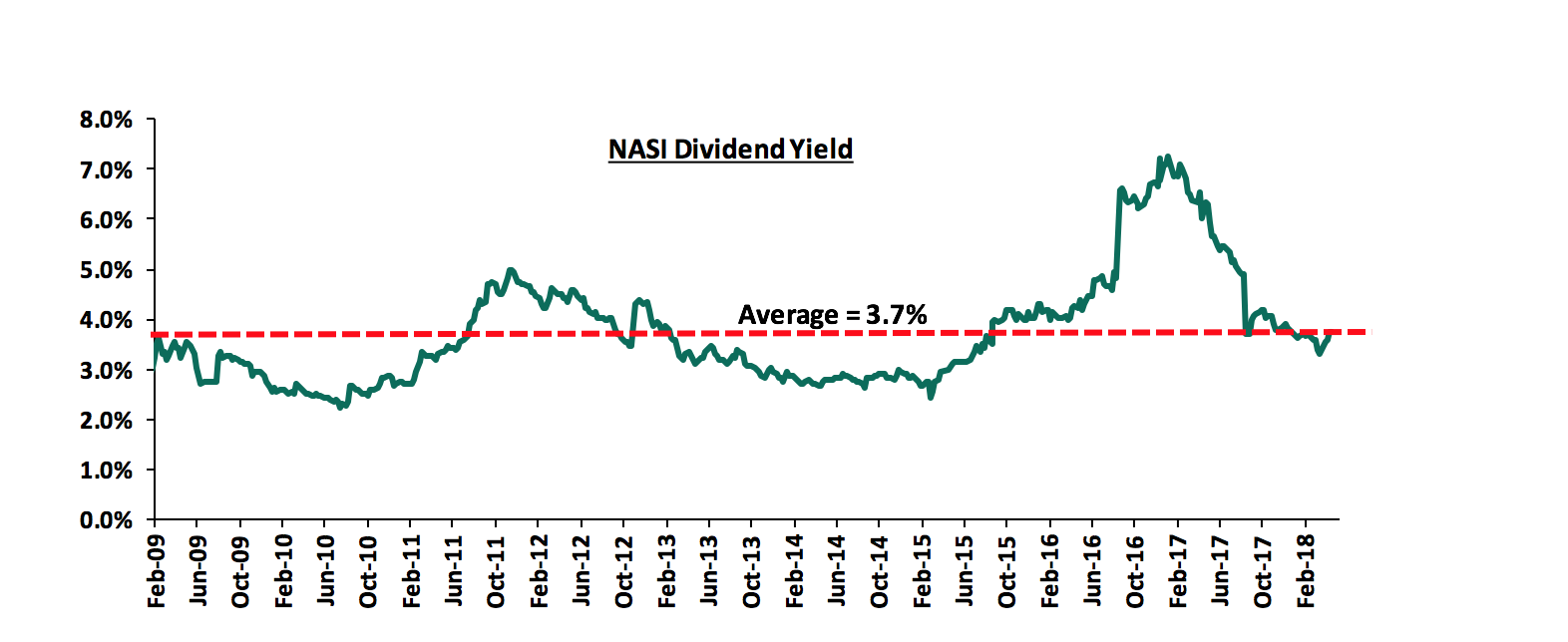

The market is currently trading at a price to earnings ratio (P/E) of 14.1x, which is 4.4% above the historical average of 13.5x, and a dividend yield of 3.7%, corresponding to the historical average of 3.7%. The current P/E valuation of 14.1x is 45.4% above the most recent trough valuation of 9.7x experienced in the first week of February 2017, and 69.9% above the previous trough valuation of 8.3x experienced in December 2011. The charts below indicate the historical P/E and dividend yields of the market.

Mortgage financier HF Group borrowed Kshs 800.0 mn in short-term loans from NIC Group and Co-operative Bank last year, according to their 2017 annual report. HF Group will repay the debt at close to the maximum interest rate allowed by law, an indication of its keen interest in getting the funding in order to facilitate payment to investors who participated in their Kshs 7.0 bn, 7-year Medium Term Note that matured last year. The loans, a Kshs 500.0 mn facility from NIC Group and a Kshs 300.0 mn note from Co-operative Bank, were to be serviced at interest rates of 14.0% and 13.0%, respectively over a one-year period; these rates rates similar to the 7-year Medium Term Note it had issued at 13.0%. These rates are above the 6.3% rate that prevailed last year for the interbank market, according to data from Central Bank of Kenya (CBK). The obligations had grown to Kshs 517.3 mn on the NIC loan and Kshs 309.6 mn on the Co-operative Bank loan as at December 2017. HF Group was also able to tap into the foreign markets, with the bank receiving additional funds from the European Investment Bank (EIB) and Ghana International Bank (GIB). The loan from EIB amounted to USD 22.0 mn (Kshs 2.2 bn) at an interest rate of 4.3% for 7-years, while GIB issued a 2-year loan of USD 15.0 mn (Kshs 1.5 bn) at an interest rate of 5.0% above 3-month LIBOR.

Commercial banks will be allowed to charge borrowers based on their risk profiles in a new proposed amendment to the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015. According to the Treasury, the proposed new loan pricing model will include a flat base rate but with an additional risk component, allowing banks to differentiate rates for different customers based on individual risk assessment. The process of drafting the bill is ongoing and it will be submitted to legislators for approval in June when presenting the budget for the 2018/19 fiscal year. The proposal comes on the backdrop of dwindling access to credit by the private sector, as the intended aim of the rate cap law to help small and medium enterprises access affordable credit was not realized. Instead, lending to SMEs was deemed too risky as lenders could not properly price risk in the wake of the rate cap, opting to lend to the government instead. The proposed amendments, however, have been met with resistance from various quarters, including Members of Parliament who have vowed not to sign the bill into law. The Consumer Federation of Kenya (Cofek) said the proposed pricing model amounts to giving banks the leeway to charge high rates on loans to customers. We are of the view that despite the amendment being a positive step in addressing the slowing private sector credit growth, it may fail to mitigate the negative effects of the rate cap on the economy; we instead propose a raft of guidelines that we have highlighted in this week’s Focus note, particularly legislation that should focus on stimulating capital markets in order to reduce reliance on banks for funding and increased options for depositors.

Below is our Equities Universe of Coverage:

|

|

all prices in Kshs unless stated otherwise |

|||||||||||

|

No. |

Company |

Price as at 04/05/18 |

Price as at 11/05/18 |

w/w Change |

YTD Change |

LTM Change |

Target Price* |

Dividend Yield |

Upside/ (Downside)** |

P/TBv Multiple |

||

|

1. |

NIC Group*** |

36.6 |

38.3 |

4.5% |

5.5% |

54.4% |

56.0 |

2.6% |

52.9% |

0.8x |

||

|

2. |

KCB Group |

48.0 |

50.0 |

4.2% |

17.0% |

47.1% |

63.7 |

4.0% |

31.3% |

1.5x |

||

|

3. |

Zenith Bank Plc |

27.5 |

28.9 |

5.1% |

12.7% |

59.0% |

33.3 |

9.3% |

30.7% |

1.1x |

||

|

4. |

Union Bank Plc |

6.7 |

6.8 |

0.7% |

(13.5%) |

51.0% |

8.2 |

0.0% |

30.4% |

0.7x |

||

|

5. |

Diamond Trust Bank |

210.0 |

205.0 |

(2.4%) |

6.8% |

62.7% |

272.9 |

1.3% |

28.8% |

1.1x |

||

|

6. |

Ghana Commercial |

6.4 |

6.4 |

0.8% |

26.7% |

23.1% |

7.7 |

5.9% |

28.3% |

1.5x |

||

|

7. |

I&M Holdings |

125.0 |

124.0 |

(0.8%) |

(2.4%) |

36.3% |

151.2 |

2.8% |

23.8% |

1.2x |

||

|

8. |

Stanbic Bank UG |

31.0 |

31.0 |

0.0% |

13.8% |

14.8% |

36.3 |

3.8% |

21.7% |

2.5x |

||

|

9. |

CRDB |

180.0 |

180.0 |

0.0% |

12.5% |

(2.7%) |

207.7 |

0.0% |

15.4% |

0.6x |

||

|

10. |

Co-operative Bank |

18.6 |

18.5 |

(0.3%) |

15.6% |

31.4% |

20.5 |

4.3% |

15.0% |

1.6x |

||

|

11. |

Equity Group |

51.0 |

51.0 |

0.0% |

28.3% |

59.4% |

54.3 |

3.9% |

14.3% |

2.2x |

||

|

12. |

Barclays Bank |

12.1 |

11.7 |

(3.3%) |

21.9% |

46.3% |

13.7 |

8.5% |

11.9% |

1.7x |

||

|

13. |

Bank of Kigali |

290.0 |

290.0 |

0.0% |

(3.3%) |

18.4% |

299.9 |

4.8% |

8.2% |

1.6x |

||

|

14. |

National Bank |

8.0 |

7.5 |

(5.7%) |

(19.8%) |

28.0% |

8.6 |

0.0% |

8.1% |

0.4x |

||

|

15. |

UBA Bank |

11.7 |

11.7 |

0.0% |

13.6% |

68.3% |

10.7 |

12.8% |

5.5% |

0.8x |

||

|

16. |

Stanbic Holdings |

91.5 |

90.0 |

(1.6%) |

11.1% |

46.3% |

87.1 |

5.8% |

2.7% |

1.1x |

||

|

17. |

HF Group*** |

10.3 |

10.0 |

(2.9%) |

(4.3%) |

9.9% |

10.0 |

3.2% |

2.5% |

0.4x |

||

|

18. |

Bank of Baroda |

150.0 |

150.0 |

0.0% |

32.7% |

36.4% |

130.6 |

1.7% |

(0.9%) |

1.2x |

||

|

19. |

StanChart KE |

210.0 |

211.0 |

0.5% |

1.4% |

9.3% |

192.6 |

5.9% |

(1.9%) |

1.7x |

||

|

20. |

Ecobank |

11.6 |

11.7 |

0.9% |

53.3% |

58.9% |

10.7 |

0.0% |

(6.7%) |

3.3x |

||

|

21. |

SBM Holdings |

7.7 |

7.7 |

0.3% |

2.9% |

1.3% |

6.6 |

3.9% |

(10.9%) |

1.1x |

||

|

22. |

Access Bank |

11.3 |

11.3 |

(0.4%) |

7.7% |

52.0% |

9.5 |

3.6% |

(11.6%) |

0.6x |

||

|

23. |

GT Bank |

45.3 |

44.3 |

(2.3%) |

8.6% |

49.7% |

37.2 |

5.4% |

(11.9%) |

2.5x |

||

|

24. |

Stanbic IBTC |

49.5 |

49.0 |

(1.0%) |

18.1% |

81.5% |

37.0 |

1.2% |

(24.0%) |

2.7x |

||

|

25. |

CAL Bank |

1.9 |

1.8 |

(4.8%) |

66.7% |

143.2% |

1.4 |

0.0% |

(28.9%) |

1.7x |

||

|

26. |

StanChart GH |

34.9 |

34.8 |

(0.3%) |

37.8% |

117.5% |

19.5 |

0.0% |

(44.3%) |

4.4x |

||

|

27. |

FBN Holdings |

12.6 |

12.3 |

(2.4%) |

39.2% |

198.8% |

6.6 |

2.0% |

(44.9%) |

0.7x |

||

|

28. |

Ecobank TN |

20.6 |

21.1 |

2.4% |

23.8% |

123.7% |

9.3 |

0.0% |

(53.8%) |

0.7x |

||

|

*Target Price as per Cytonn Analyst estimates |

||||||||||||

|

**Upside / (Downside) is adjusted for Dividend Yield |

||||||||||||

|

***Banks in which Cytonn and/or its affiliates holds a stake. For full disclosure, Cytonn and/or its affiliates holds a significant stake in NIC Bank, ranking as the 5th largest shareholder |

||||||||||||

We are “NEUTRAL” on equities for investors with a short-term investment horizon since the market has rallied and brought the market P/E slightly above its’ historical average. However, pockets of value exist, with a number of undervalued sectors like Financial Services, which provide an attractive entry point for long-term investors, and with expectations of higher corporate earnings this year, we are “POSITIVE” for investors with a long-term investment horizon.

Sanlam Kenya, a financial services company listed on the Nairobi Securities Exchange, which mainly deals in insurance, investments and retirements schemes, has invested an additional Kshs 121.7 mn in equity in Sanlam General according to their annual report 2017. Sanlam Kenya, then Pan Africa Insurance Holdings Limited (Pan Africa), first acquired 31,948,950 ordinary shares of Gateway Insurance, a 51.0% stake, in March 2015 for Kshs 561.0 mn. It also subscribed to additional shares in Gateway amounting to Kshs 139.7 mn to increase its shareholding to 56.5% in the same year. After the transaction, it renamed Gateway Insurance to Sanlam General. The first and second transaction valued the company at Kshs 1.1 bn and Kshs 1.2 bn, respectively. The acquisitions were carried out at a P/Bv multiple of 1.1x. The acquisition was a strategic move for the company to re-enter the general insurance market and to enable them to offer their clients with more financial solutions. In 2016, Sanlam Kenya made an additional investment of Kshs 213.7 mn in Sanlam General, increasing their stake in the company to 67.6%. The additional investment made in 2017 raises Sanlam Kenya’s total investment in the subsidiary to Kshs 1.0 bn. The investment, however, left their ownership unchanged as the minority shareholders also made an additional investment of Kshs 66.5 mn. Sanlam stated that its capital commitment in the unit is Kshs 496.6 mn, as a result of an impairment charge of Kshs 539.6 mn, which was recognized in the company’s statement of profit or loss for the year ended 31st December 2015, as a result of prior year adjustments passed in the accounting records of Gateway in 2015.

AccorHotels, a French multinational hotel group, which operates in 95 countries, signed an agreement with Mövenpick Holding and Kingdom Holding to acquire a 100% stake of Mövenpick Hotels & Resorts for 560.0 mn Swiss Francs (USD 558.3 mn). According to their statement, the enterprise value of 560.0 mn Swiss Francs implies a multiple of 14.9x expected 2019 EBITDA of USD 37.5 mn. Mövenpick Hotels & Resorts is a hotel management company headquartered in Baar, Switzerland. It is currently owned by Mövenpick Holding who have a stake of 66.7%, and the Saudi based Kingdom Group who have a stake of 33.3%. Mövenpick Hotels & Resorts operates in 27 countries with 84 hotels, approximately 20,000 rooms and a particularly strong presence in Europe and the Middle East. In Africa, Mövenpick Hotels & Resorts operates 24 hotels in 5 countries; 16 Hotels in Egypt, 3 Hotels in Tunisia, 3 Hotels in Morocco, 1 Hotel in Ghana and 1 Hotel in Kenya. The Mövenpick Hotel & Residences Nairobi is located in Westlands. They have focused their growth in Europe, The Middle East, Africa and Asia. They plan to open 42 additional hotels by 2021, adding a further 11,000 rooms to its portfolio, with 5 new hotel developments in Africa; 2 in Egypt, 1 in Cote d’Ivoire, 1 in Ethiopia, and 1 in Nigeria. The acquisition is important for both parties, as it will accelerate AccorHotels growth in emerging markets particularly in the Middle East, Africa and Asia Pacific. Mövenpick Hotels & Resorts will benefit from AccorHotels’ loyalty program, distribution channels and operating systems, which will help optimize their performance.

The last decade has seen many global operators opening quality hotels in key markets in Sub-Saharan Africa like South Africa, Mauritius and Kenya with the supply of new hotels attributed to high occupancy rates. South Africa, Mauritius and Kenya had occupancy rates of 62%, 79% and 53%, respectively in 2017. The Average Daily Rate (ADR) was USD 101, USD 212 and USD 143, respectively in the same year. The ADR in the three counties grew by 7.8%, 5.5% and 0.7%, respectively, from the previous year. The hospitality sector in Sub-Saharan Africa is set to perform well driven by the following factors:

- A growing population and expected strong economic growth where GDP is expected to grow by 3.4% in 2018, and 3.5% in 2019, from an expected 2.7% in 2017,

- Growth in both international and domestic travelers to the market,

- An expected improvement in hotel standards as there is a shortage of quality hotels in Africa and as the middle class grows, there is higher demand for quality hotels, and,

- Increase in intra-African travel as the continent experiences better connectivity, access to low-cost airlines, and more countries embracing visa-free travel within Sub-Saharan Africa.

In Kenya, we expect further growth in the hospitality sector as a result of (i) restoration of political calm, (ii) the revision of negative travel advisories, warning international citizens, e.g. from the United States against visiting Kenya, (iii) positive reviews from travel advisories such as Trip Advisor who ranked Nairobi as the 3rd best place to visit in 2018, only behind Ishigaki Island in Japan and Kapaa in Hawaii, and The Travel Corporation who ranked travel to Kenya as one of the top 10 transformative travel experiences in the world, (iv) improved hotel standards as hotels rebrand while some embark on refurbishment and expansion, and (v) improved flight operations and systems such as direct flights from the USA to Kenya, which are set to commence this year.

Private equity investments in Africa remains robust as evidenced by the increasing investor interest, which is attributed to; (i) rapid urbanization, a resilient and adapting middle class and increased consumerism, (ii) the attractive valuations in Sub Saharan Africa’s private markets compared to its public markets, (iii) the attractive valuations in Sub Saharan Africa’s markets compared to global markets, and (iv) better economic projections in Sub Sahara Africa compared to global markets. We remain bullish on PE as an asset class in Sub-Sahara Africa. Going forward, the increasing investor interest and stable macro-economic environment will continue to boost deal flow into African markets.

During the week, Erdemann Property Ltd, a Nairobi based property development company, announced their plans to construct eight 34-storey blocks, on 5.7 acres of land (2.3 hectares) in Ngara Estate, Nairobi. The mixed-use development dubbed “The Rier Estate”, will feature a total of 1,632 apartments (537, 3-bedroom units, 1,088, 2-bedrooms, and 7, 1-bedroom units), with 875 parking slots and a shopping complex with 60 outlets. In our opinion, the project targets families, hence the higher number of the 2 and 3 bedroom units, compared to the of 1 bedroom units. The developer intends to adopt an affordable housing model; however, the unit prices and sizes remain unspecified. To fast-track commencement of the development, the firm went ahead to seek approvals from the Nairobi City County to allow for the upgrade of Jadongo Road to improve accessibility to the property. This will mark the firm’s fourth residential project after Metro Fairview, which is a 12-storey development with 206 units in Pangani, Greatwall Gardens with approximately 2,070 apartments in Athi River and Great Wall Apartments Phase I, II and III comprising 1,422 units in Mlolongo. The project is an example of how local and international investors are making inroads in the real estate sector, riding on the back of positive fundamentals such as:

- A high urbanization rate of 4.4% against the global average of 2.1%,

- An expanding middle class with increased purchasing power due to higher disposable income, whichincreased to Kshs 6.6 tn in 2016 from Kshs 5.7 tn in 2015 according to KNBS Economic Survey 2017,

- High population growth with a 5-year CAGR at 2.6% compared to the global average of 1.2%, and,

- Government incentives such as the 15.0% corporate tax relief to developers who put up at least 100 low-cost residential houses annually, digitization of the Lands Ministry, scrapping of NEMA and NCA levies, and inclusion of provision of affordable housing in its 4 key strategic pillars of focus for the period 2017-2022, “Big Four”, alongside food security, manufacturing and universal healthcare.

The project, however, highlights one of the challenges that the sector continues to face, that is, inadequate infrastructure, where developers are forced to incur the costs of providing vital services such as roads and sewerage systems in order to deliver bankable developments. Such costs are passed on to end-buyers limiting the affordability of houses. The government has, however, through the Big Four strategy, proposed deductions on taxable income of 25.0% of the development cost, where infrastructure has been provided by a developer, which is an incentive that aims to encourage investment in affordable housing.

The mapping of about 7,000 acres of land for the construction of low-cost houses in Mombasa, Kisumu, Eldoret, Nairobi and Nakuru through Public Private Partnerships shows the commitment of the government in achieving its agenda on low-cost housing. Nevertheless, the residential sector has its challenges, where during the week we saw, Nakuru County Governor, Lee Kinyanjui, issue a request to the Ministry of Lands to revoke deeds issued for a piece of land in Naivasha. The 22.4-acre piece of land planned for a Kshs 2.0 bn housing project supported by the World Bank, had allegedly been allocated to a private developer initially in an irregular manner. This is a setback to the 5-year strategy by the government to address the housing deficit, since the project would have added stock of 2,000 low-cost houses to the market, comprising 1 and 2-bedroom units. We recommend that developers ensure they obtain all the relevant valid approvals and conduct thorough due diligence on their development sites to minimize the disruption of project progress.

During the week, the Kenya Mortgage Refinancing Company (KMRC) received support of Kshs 15.1 bn from the World Bank. KMRC, which is currently being incorporated, was created to reduce the liquidity risk that commercial banks face in offering long-term credit, as well as enable potential home-buyers access financing with ease. According to Hon. Henry Rotich, Treasury’s Cabinet Secretary, the government is discussing the likelihood of increasing the funding of the project with other development partners such as local commercial banks and the African Development Bank (AfDB). We are however of the view that in order for the KMRC to be effective, there is need for more effort towards the attainment of a stable and lower interest rate environment, and especially on government securities, which may crowd out KMRC from accessing the needed funding. Our topical on The Kenya Mortgage Refinancing Company, expounds more on how the facility works and the effect of the same on housing in Kenya.

In other highlights;

- On safety, the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) has kicked off the vetting of buildings, both under construction and existing premises, for compliance with solar heating rules. According to the energy (solar water heating) regulations, premises with hot water requirements of more than 100 litres per day must be fitted with solar heating systems, with the aim of encouraging use of renewable sources of energy. The regulation applies to domestic houses with at least 3-bedrooms, colleges and boarding schools with 20 or more students, hostels and lodges with at least 4-beds, just to mention a few. Failure of compliance to these regulations will see property owners risk a Kshs 1.0 mn fine or one year in jail,

- In the retail sector, troubled retail chain Nakumatt Holdings closed its City Hall and Galleria Mall branches owing to its accumulated unpaid dues. The latest closure was occasioned by Tuskys pulling the plug on a rescue partnership it had been pursuing with Nakumatt. The retailer, which had 62 branches across East Africa, also recently closed its branches at City Hall Mombasa and the Village Market in Nairobi, bringing the number of branches still in operation to approximately 20. We attribute the closure to challenges regarding accumulated debt incurred during the retail store’s rapid expansion and poor supply chain management. The closures have resulted in the expansion of other local and international retailers such as Naivas, Carrefour and Tuskys, who have occupied the vacated spaces, an indication of sustained optimism in the retail sector.

We expect the real estate sector to continue recording increased activity, with the continued supply of housing units to meet the existing deficit, mortgage liquidity facility enabling more home purchases, and thus, boosting investor confidence in the sector, in addition to the stable economic environment.

We revisit the interest rate cap following the recent announcement by the Treasury that they were in the process of completing a draft proposal that will address credit management in the economy. Treasury Cabinet Secretary, Henry Rotich, stated that the draft law would not only be centered on the cost of credit, but will also present some consumer protection policies. “The package of reforms is expected to address the real cause of the high credit cost in Kenya, and eventually lead to the elimination of the law capping interest rates,” said Henry Rotich during the launch of the 2018 Economic Survey Report in Nairobi. A repeal of the law was one of the promises made to the IMF, for the extension of the USD 1.5 bn stand-by credit and precautionary facility. The IMF said in a statement, “On March 12, the executive board of the IMF approved Kenyan authorities’ request for a 6-month extension of the country’s stand-by arrangement to allow additional time to complete outstanding reviews”. The availability of the credit facility was tied to the Treasury’s fulfillment of the promise it made to cut back on the fiscal deficit through a raft of budget consolidation measures, including cutbacks on public spending, together with a repeal of the interest rate cap law. We therefore revisit the issue of the interest rate cap, focusing on;

- Background of the Interest Rate Cap Legislation - What Led to Its Enactment?

- A Review of the Effects It Has Had So Far In Kenya

- Case Studies of Other Interest Rate Cap Regimes in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Our Views on the Way Forward - including our view of what should be included as part of the amendment or elimination of the law, with an emphasis on stimulating capital market alternatives.

Section I: Background of the Interest Rate Cap Legislation - What Led to Its Enactment?

The enactment of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, that capped lending rates at 4.0% above the Central Bank Rate (CBR), and deposit rates at 70.0% of the CBR, came against a backdrop of low trust in the Kenyan banking sector about credit pricing due to various reasons;

- First, the period was marred with several failures of banks such as Chase Bank Limited, Imperial Bank Limited and Dubai Bank, due to isolated corporate governance lapses. The failure of these banks rendered depositors helpless and unable to access their deposits in these banks. The fact that no single prosecution was ongoing at the time, for alleged malpractices that led to the collapse of some of the banks such as Imperial Bank, only served to infuriate depositors who had their deposits locked in these institutions,

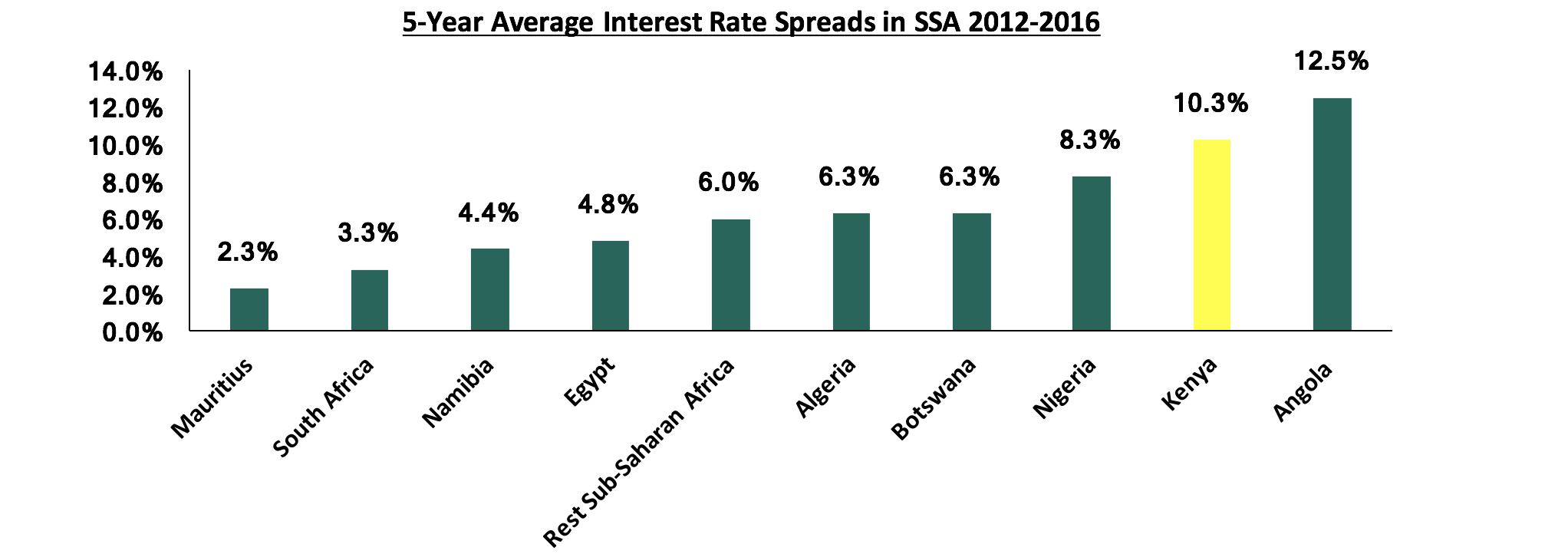

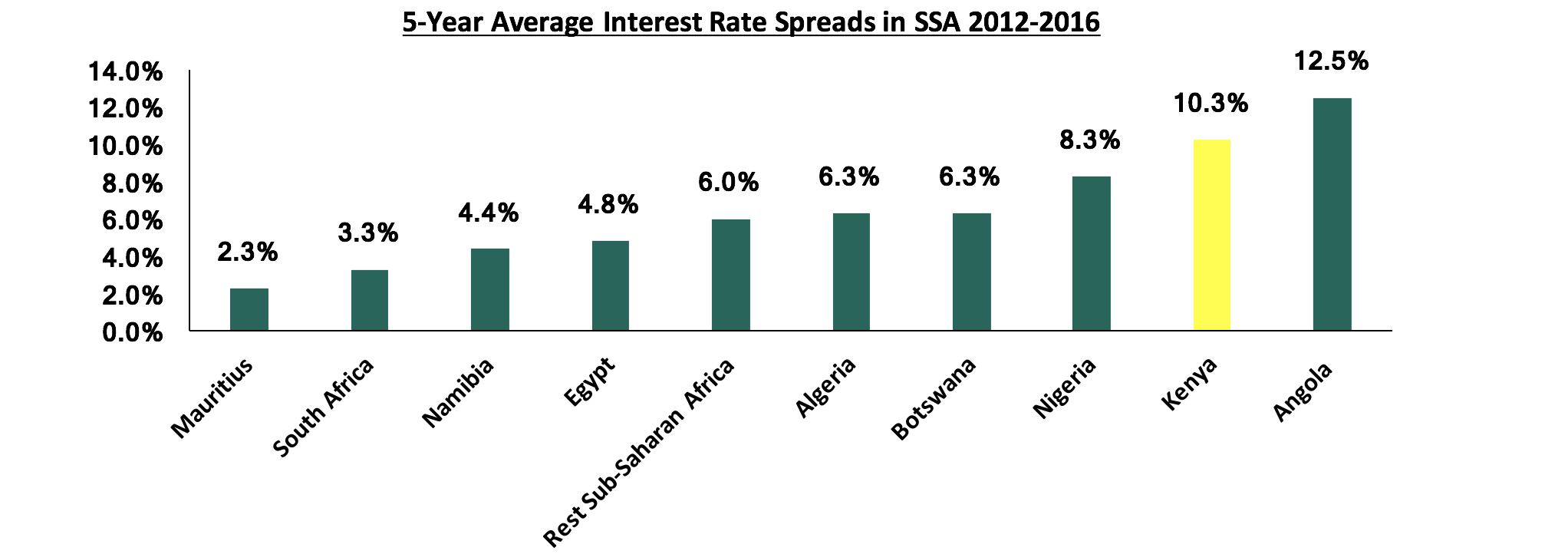

- The cost of credit was high at approximately 21.0% per annum, yet on the other hand, the interest earned on deposits placed in banks was low, at approximately 5.0% per annum. This led to a high spread between the lending rates and deposit rates as shown in the graph below,

- Credit accessibility was also subdued under this regime of expensive debt, as a lot of individuals opted out of seeking debt from commercial banks, owing to the opacity involved in the loan terms. Thus most individuals and entities opted for alternative sources of funding such as “soft loans” other than from banks, and,

- Banks are the primary source of business funding in the country, providing 95.0% of funding, with other alternative sources such as the capital markets providing a combined 5.0%, compared to developed markets where banks provide only 40.0% of the credit in the economy. This skewed source of funding in Kenya was in favor of the banks, as they would price loans on their terms, as opposed to the optimal market rate. This low level of competition from alternative sources of funding in part contributed to high interest rate charges levied by banks.

This fueled anger from the Kenyan public, who accused banks of unfair practice in the quest for extremely high profits at the expense of the borrowers and savers. As a result, banks in Kenya had been making one of the highest profits in the region, as shown in the charts below for the period between 2012 and 2016:

Source: World Bank

Source: IMF

This culminated in the interest rate cap bill being tabled in parliament, and due to its populist nature was passed and signed into law by the President on August 24th, 2016, and it was enforced from September 14th 2016.

Our view has always been that the interest rate cap regime would have adverse effect on the economy, and by extension, to the Kenyan People. We have previously written about this in five focus notes, namely:

- Interest Rate Cap is Kenya’s Brexit - Popular But Unwise, dated 21st August 2016, three days before the signing into law of the interest rate cap, where we first expressed our view that the interest rate cap would have a clear negative impact on the economy. We noted that free markets tend to be strongly correlated with stronger economic growth, plus we noted the lack of compelling evidence of any economy where interest rate capping was successful, as evidenced by the World Bank report on the capping of interest rates in 76 countries around the world. In Zambia, for example, interest rate caps were introduced in December 2012 and repealed 3-years later, in November 2015, after the impact was found to be detrimental to the economy. We called for the implementation of a strong consumer protection agency and framework, coupled with the promotion of initiatives for competing alternative products and channels,

- Impact of the Interest Rate Cap, dated 28th August 2016, four days after the interest rate cap bill was signed into law, where we highlighted the immediate effects of the interest rate cap, as banking stocks lost 15.6% in 2-days. Here, we re-iterated our stance on the negative effects of the interest rate cap, while identifying the winners and losers of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015,

- The State of Interest Rate Caps, dated 14th May 2017, 9-months after the interest rate cap was signed into law, where we assessed the interest rate cap and its effects on private sector credit growth, the banking sector and the economy in general, following concerns raised by the IMF. We noted that the law had the effect of (i) inhibiting access to credit by SMEs and other “small borrowers” whom banks cited as being unable to fit within the 4.0% risk premium, and (ii) contributed to subduing of private sector credit growth, which was recorded at 4.0% in March 2017. We suggested that policymakers review the legislation, highlighting that there existed, and continues to exist, opportunities for structured financial products and private equity players to come in and provide capital for SMEs and other businesses to grow, and consequently improve private sector credit growth,

- Update on Effect on Interest Rate Caps on Credit Growth and Cost of Credit, dated 23rd July 2017, approximately 1-year after the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015 was signed into law, where we analyzed the decline in private sector credit growth and lending by commercial banks, coupled with the elevated total cost of credit, which was higher than the legislated 14.0%, as banks loaded excessive additional charges, while noting that the large banks, which control a substantial amount of the banking sector loan portfolio, were the most expensive. We suggested (i) a repeal or modification of the interest rate cap, (ii) increased transparency, (iii) improved and more accommodating regulation, (iv) consumer education, and (v) diversification of funding sources into alternatives, and,

- The Total Cost of Credit Post Rate Cap, dated 14th January 2018, where we analyzed the true cost of credit, initiatives put in place to make credit cheaper and more accessible, the impact of the interest rate cap on private sector credit growth, and what more can be done do remedy the effects of the interest rate cap.

Having now been in effect for 21-months, plans to review the law have been gaining traction because there is significant evidence that its intended objectives have not been achieved. On the campaign for review are banks, private sector players, organizations such as the IMF, and the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK). The CBK has mentioned that according to its research, the interest rate cap has failed to achieve the objectives it was drafted for, mainly access to credit at favorable pricing. Instead, the cap has (i) inhibited the growth of private sector credit in the economy, and (ii) made it difficult for the enforcement of monetary policy action, as any action on the benchmark CBR would trickle down to credit pricing. The IMF has also been vocal in its recommendation of a repeal of the law. The IMF noted that the rate cap had the effect of locking out a lot of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) from accessing credit, and with SMEs being the largest proportion of the private sector, this translated to reduced economic output. A repeal of the law was also part of the commitments made by the National Treasury when seeking an extension to use the USD 1.5 bn credit and precautionary facility by the IMF. The facility is normally used in case of any economic shocks that may affect the economy. The Cabinet Secretary thus indicated that a draft proposal that will address credit management in the economy would be tabled in parliament in June this year.

On the flip side, some organizations have come out in support of the interest rate cap, namely the Institute of Certified Public Accountants of Kenya (ICPAK). The organization has raised concerns that a repeal of the interest rate cap would lead to a return to the previous regime characterized by exorbitant borrowing costs. They argue that although the concerns raised are genuine, it is still too early to assess the impact of the rate cap to the economy, and that the challenges experienced are not directly attributable to the rate cap. ICPAK together with the Consumer Federation of Kenya (CoFEK), are of the view that we need to address the challenges that led to the enactment of rate cap, mainly the high cost of borrowing, and ensure that there is a better balance between the interests of the market players and those of the consumers.

Section II: A Review of the Effects It Has Had So Far In Kenya

The interest rate cap has had the following four key effects to Kenya’s economy since its enactment:

- Private Sector Credit Growth Dropped Dramatically

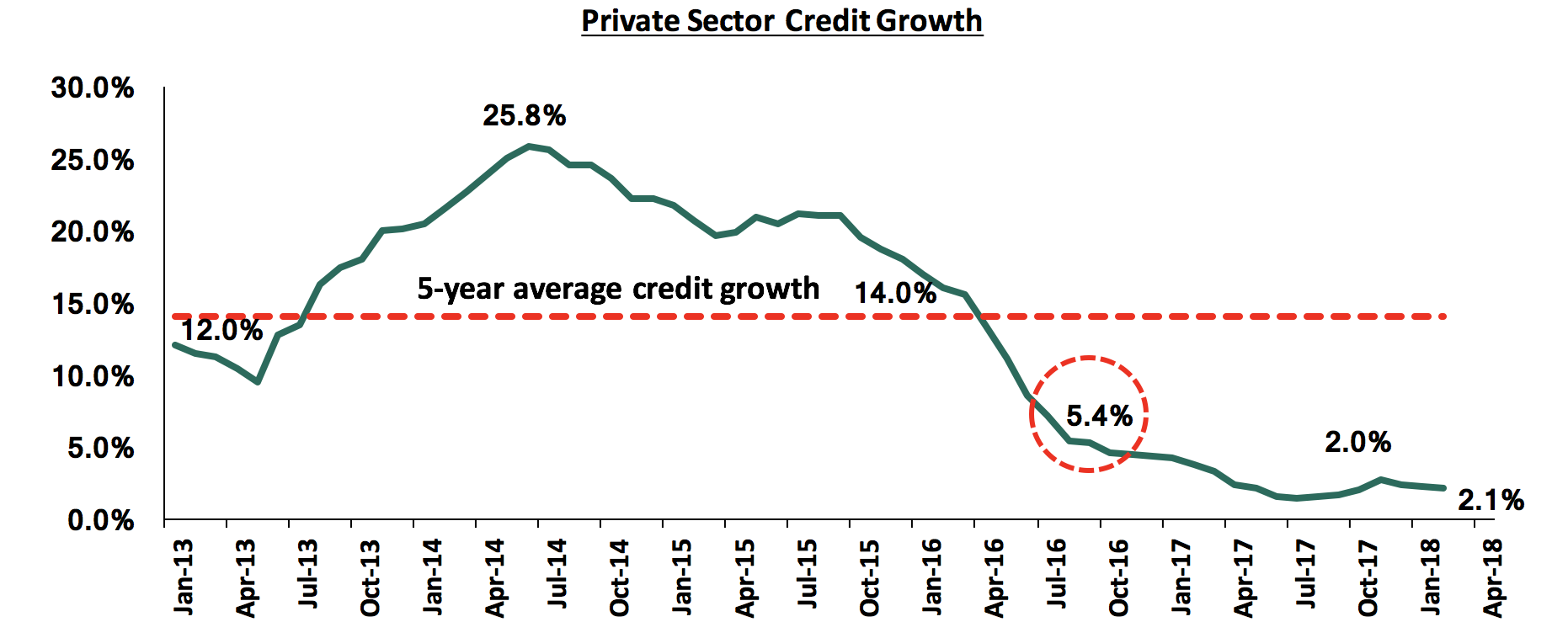

Private sector credit growth in Kenya has been declining, and the enactment of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, had the adverse effect of further subduing credit growth. The law capped lending rates at 4.0% points above the CBR. This made it difficult for banks to price some of the borrowers within the set margins, a majority being SMEs, as they were perceived “risky borrowers”. Banks thus invested in asset classes with higher returns on a risk-adjusted basis, such as government securities. As can be seen from the graph below, private sector credit growth touched a high of 25.8% in June 2014, and has averaged 14.0% over the last five-years, but has dropped to 2.0% levels after the capping of interest rates.

According to the September 2016 CBK Credit Officer Survey, banks tightened their credit standards immediately after the interest rate cap was enforced in Q4’2016. The sectors mainly affected were Agriculture, Financial Services, Energy, Trade, Transport, Personal/ Household and Manufacturing. Tighter credit standards have persisted, and private sector credit has not accelerated since the cap was effected, coming in at 2.1% in March 2018. The resultant effect is that the legislation has not achieved its primary objective of improving credit growth to the private sector.

- Loan Accessibility Reduced

Immediately after the enactment of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, banks saw an increase in demand for loans, as the number of loan applications increased by 20.0% in Q4’2016 according to the CBK Credit Officer Survey of October-December 2016. This was due to borrowers attempting to get access to cheaper credit. However, this demand was not matched with supply of loans by banks as evidenced by:

- Decline in the number of loan accounts: The number of loan accounts in large banks (Tier I) declined by 27.8%, the largest among the three tiers, followed by Tier II banks with a decline of 11.1% between October 2016 and June 2017. Tier III banks however had the number of loan accounts increase by 4.5%. This shows that loan accessibility reduced, with the larger tier banks being the front-runners in reducing lending, especially to small borrowers. Thus, the rate cap law hampered credit accessibility to small scale borrowers in the private sector, another objective of the interest rate cap that was not achieved, and

- Increase in average loan size: The average loan size increased by 36.0% to Kshs 548,000 from Kshs 402,000 between October 2016 and June 2017. This points to lower credit access by smaller borrowers, while also demonstrating that credit was extended to larger and more “secure” borrowers. The increase in the average loan size was highest for the Tourism and Hotels sector, which had the average loan size grow by 76.0%. Building and Construction had the loan size increase by 63.0%. On the other hand, Personal & Household was the only segment that witnessed a decrease in loan size, with the average loan size declining by 24.0%. The CBK noted that banks of different tiers recorded different increments in loan size, with Tier I banks recording a 42.0% increase in loan size to Kshs 396,000 from Kshs 278,000, followed by Tier III banks at 21.0% to Kshs 2.0 mn from Kshs 1.7 mn, and Tier II banks by 2.0% to Kshs 1.8 mn from Kshs 1.7 mn. The huge increase in average loan size by Tier I banks demonstrates their unwillingness to lend to the small borrowers and SMEs, who are generally riskier borrowers who could not fit the legislated rates.

- Decrease in average loan tenures: The average loan tenure declined by 50.0% to 18-24 months compared to 36-48 months prior to the introduction of the interest rate cap. This is due to bank’s increasing their sensitivity to risk, thereby opting to extend only short-term and secured lending facilities to borrowers, rather than longer-terms loans to be used for investments, according to the latest survey by the Kenya Bankers Association (KBA) on the effects of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015. As per the KBA report, reversing the impact of the rate cap could take up to 12-months, especially to allow the market to start correcting on credit pricing and disbursement, underlining the need for swift action to review the law and repeal the rate cap.

- Bank’s Operating Models Changed to Mitigate Effects of the Rate Cap Legislation

The enactment of the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, saw banks changing their business and operating models to compensate for reduced interest income (their major source of income) as a result of the capped interest rates. Furthermore, the enactment of the law saw increased cost of funds, as deposit rates were floored at 70.0% of the CBR, which meant increased interest expense to banks. With the reduction in income (interest income), and increased cost of funds, the banks’ profitability margins were set to reduce. Thus, banks adapted to this tough operating environment by adopting new operating models in several ways:

- Increased focus on Non-Funded Income (NFI): The increased cost of funds from the higher deposit rates coupled with reduced interest income from loans led to banks’ increased focus on NFI. This is evidenced by the fact that the proportion of non-interest income to total income stood at 28.4% in September 2016, and eventually rose to the current 33.6%. Non-interest charges on loans in the form of fees on loans also increased. As such, the entire cost of loans as measured by the Annual Percentage Rate (APR) was still higher than 14.0%, remaining consistent at 16.7%, albeit lower than the average of 21.0% before the enactment of the interest rate cap, but mainly because banks shunned away from risky borrowers. To increase NFI, banks increased “other fees”, e.g. appraisal fees, that was made to mitigate the impacts of reduced income due to the reduced interest rates on loans charged,

- Increased focus on transactional accounts: Banks also increased their focus to growing their transactional accounts as opposed to interest earning accounts. Furthermore, many commercial banks moved to reclassify deposit accounts to limit the number of accounts that qualify to earn the interest set in the amended law. Some banks sent out notices to customers indicating that only fixed accounts qualified to earn interest,

- Increased lending to the government: There was increased lending to government rather than individuals and the private sector, given the higher risk-adjusted returns offered by government debt. Banks increasingly allocated funds to government securities, as opposed to lending, even as the mobilized deposits increased. This is evidenced by the increase in banks’ share of total government debt, that stood at 45.1% in 2015, which increased to 51.5% in 2016 after the enactment of the rate cap law, and is at 55.0% currently, and,

- Cost rationalization: Banks also stepped up their cost rationalization efforts by increasing the use of alternative channels by mainly leveraging on technology such as mobile money and internet banking to improve efficiency and consequently reduce costs associated with the traditional brick and mortar approach. This led to the closure of branches and staff layoffs in a bid to retain the profit margins in the tough operating environment, due to depressed interest income.

Banks’ profitability thus generally reduced after the enactment of the cap, as evidenced by the return on equity and return on assets that declined to 19.8% and 2.3%, compared to the 5-year averages of 29.2% and 4.4%, respectively. The listed banking sector recorded a decline in earnings by 1.0% in 2017, from a growth of 4.4% in 2016. Banks have adjusted their business models to mitigate against the effects of the legislation, rather than reduce credit costs or increase access to credit, which were the initial objectives of the law. The “punishment” that the public wanted meted out to the banks has been mitigated by the sector using the above changes in operating model. We are of the view that any repeal or amendment will also be mitigated by the dynamic banking sector, hence the best approach to addressing banking sector dominance and overreliance in the sector is to stimulate alternative funding sources.

- Weakening of Monetary Policy Effectiveness

The Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, has made it difficult for the Central Bank to conduct its monetary policy function. This is majorly because any alteration to the CBR would directly affect the deposit and lending rates. During the period of enactment of the interest rate cap law, private sector credit was on a declining trend. Inflation was also low and was expected to decline. Therefore, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decided to lower the CBR so as to inject growth stimulus into the economy. This however had the opposite and unintended result as credit growth declined further. Thus, the monetary policy decision failed to yield the expected results of improving credit growth. Expansionary monetary policy thus is difficult to implement since lowering the CBR has the effect of lowering the lending rates and as a consequence, banks find it even more difficult to price for risk at the lower interest rates, leading to pricing out of even more risky borrowers, and hence further reducing access to credit. On the other hand, if the CBK was to employ a contractionary monetary policy, so as to reduce inflation and credit growth for example, then raising the CBR would have the converse effect of increasing the supply of credit in the economy since banks would be able to admit more riskier borrowers. Therefore, the monetary policy function of the Central Bank cannot be effectively executed in a regime with capped interest rates, and especially where the pricing is pegged on the Central Bank Policy rate such as the CBR in this case. This hampers the CBK’s ability to carry out its mandate of ensuring price stability in the economy under a capped interest rate regime.

Having taken the above four effects into consideration, it is clear that the legislation has not achieved its intended effect. The IMF has maintained that with the rate cap in place, lending to Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises has been inhibited, and since they are significant contributors to the country’s output, then GDP growth is negatively affected.

To grant the extension to the precautionary credit facility, IMF set conditions for both fiscal consolidation and modification of interest rate controls. The National Treasury as a result agreed to the conditions set by the IMF and has a 6-months grace period to effect these conditions. The stand-by facility is especially important in the event the economy experiences external shocks that may put upward pressure on the Kenya Shilling.

This leaves the inevitable proposition of a repeal of the rate cap law, just as was the case in Zambia. However, it will be difficult owing to the populist nature of the law, even though it makes economic sense to repeal it. Consideration however has to be made of the challenges that lead to the initial enactment of the law.

Section III: Case Studies of Other Interest Rate Cap Regimes in Sub Saharan Africa

We are not surprised that the interest rate cap regime has not been effective, given the history of such policy action in other countries. We present two quick case studies:

- Zambia

The Central Bank of Zambia introduced a cap on the effective interest rates charged by banks at 9% above the Central Bank Rate in 2012. This led to the Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFI) that mainly included microfinance institutions, leasing finance institutions and building societies, thriving by providing credit to people who were perceived ‘‘risky borrowers’’ and could not be priced within the interest rate cap. Borrowing costs rocketed, with microfinance institutions in the country charging an average effective annual rate of 109.2% on the loans issued. These high costs led to increased public unrest, which culminated with the Central Bank of Zambia introducing another interest rate cap on the effective interest rates charged by Non-Bank Financial Institutions. Thus, the maximum effective annual lending rate for all companies designated as Microfinance institutions was capped at 42% p.a. and all other NBFI had the maximum annual effective lending rate at 30% p.a. The second interest rate cap resulted in a reduction in lending, especially to the middle and low-income group, that initially benefited from access to these loans. Furthermore, access to credit from more established institutions such as commercial banks was also reduced, since most people seeking credit were already highly leveraged and already falling into a debt trap. Thus, they could not be priced within the set margins of commercial banks at 9% of the Central Bank Rate. This had the effect of reducing overall credit to personal and household entities, together with small businesses, leading to reduced economic output. As a result, the Zambian Government repealed the interest rate caps, and replaced the cap with a raft of consumer protection policies in November 2015. The policies focused on reducing the opacity in the pricing of the loans by ensuring full disclosures to the borrowers. The conditions for the repeal stipulated tough sanctions for any institutions defying the set out consumer protection policies. The Central Bank even went a step further and issued a disclosure template that will be issued to the prospective borrower by the issuing institutions, so as to provide full disclosure and more clarity on the borrowing terms. This has aided in reducing the overall cost of borrowing from the high average of 109.2% p.a. before to 65.2% p.a. as at 31st March 2017, albeit this is still too high.

- West Africa Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU)

The WAEMU is a combination of eight countries in the West African region that comprises of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo. The region had witnessed a proliferation of microfinance institutions. A huge proportion of the funding for a majority of these institutions was from grants obtained from international financial institutions and their respective governments. Despite the cheap cost of funding, the cost of credit skyrocketed and as a result, there was public outcry for the reduction and capping of the borrowing rates and for regulation in terms of how microfinance institutions price credit. The region’s Central Bank capped lending rates at 15% for banks and 24% for non-banking institutions in 1997. However, after the imposition of the rate cap, many microfinance institutions withdrew from areas mainly occupied by low income households, their main clientele. This saw reduced credit accessibility by these households as microfinance institutions were unable to price these borrowers within the margins set by the Central Bank. This had the overall effect of locking out low-income borrowers, since these institutions adopted strict lending policies and focused on secured lending to larger and more “secure” borrowers, as opposed to the small borrowers that form the majority of the population. Thus, the cap had the opposite intended effects as credit accessibility was reduced for low earners. However, the interest rate cap remains in place to date. The World Bank has repeatedly called for the WAEMU to consider amending the interest rate caps, either in a partial or phased liberalization plan, coupled with increased transparency requirements and standardized disclosures, as the caps have also constrained the offer of innovative digital credit and savings products to the unbanked, thereby limiting the growth of financial inclusion.

Section IV: Our Views on the Way Forward:

It is clear to us that we need to urgently repeal or at least significantly review the Banking (Amendment) Act, 2015, given the current regulatory framework, as it has hampered credit growth, evidenced by the continued decline of private sector credit growth, which is at 2.1% as at March 2018, below the 5-year average of 14.0%; but a repeal ought to contain several components as there is no single silver bullet. We are however concerned that the repeal is more focused on banks, yet to manage bank dominance and funding reliance we have to focus on expanding capital markets as an alternative to banks. We see a combination of the following 7 measures as necessary as part of the repeal:

- Legislation and policies to promote competing sources of financing should be the centerpiece of the repeal legislation: A lot of legislative action has focused on the banks, yet we also need legislation to promote competing products that will diversify funding sources, which will enable borrowers to tap into alternative avenues of funding that are more flexible and pocket-friendly. This can be done through the promotion of initiatives for competing and alternative products and channels, in order to make the banking sector more competitive. In developed economies, 40% of business funding comes from the banking sector, with 60% coming from non-bank institutional funding. In Kenya, 95% of all funding is bank funding, and only 5% from non-bank institutional funding, showing that the economy is highly dominated by the banking sector and should have more alternative and capital market products for funding businesses. Alternative investment managers and the capital markets regulators need to look at how to enhance non-bank funding, such as high yield investment vehicles, some of which include High Yield Notes and Cash Management Solution, CMS, products. The products offer investors with cash to invest at a rate of about 18% to 19% per annum, equivalent to what the fund takers, such as real estate developers, would have to pay to get funds from the banks. Instead of a saver taking money to the bank and getting negligible returns, they can just invest in a funding vehicle where the business would pay them the same 18% to 19% per annum that they would pay to get the same money from the bank. For the saver, it helps improve their rate from low rates, at best 7% per annum, to as high as 18% per annum, and for the business seeking funding, it helps them access funding much faster to grow their business. Promoting alternative funding is also essential to the affordable housing piece of the “Big Four” government agenda, which requires capital markets funding,

- Consumer protection: The implementation of a strong consumer protection, education agency and framework, to include robust disclosures on cost of credit, free and accessible consumer education, enforcement of disclosures on borrowings and interest rates, while also handling issues of contention and concerns from consumers,

- Promote capital markets infrastructure: This is necessary in both regulated and private markets. The Capital Markets Authority (CMA) could aid in enhancing the capital markets’ depth by making it easier for new and structurally unique products to be introduced in the capital and financial markets. This may then enhance returns, with the benefits of reduced risk compared to the traditional conventional investment securities. This will then enable the diversion of the funds from banks into other investment vehicles that yield returns that far eclipse those obtained from deposits in banks, thereby leading to a faster capital formation in the economy. Advocacy groups, such as the East African Forum for Structured Products (EAFSP) and East Africa Venture Capital Association (EAVCA), should engage policy makers on the need for alternative and structured products as viable options to bank funding, hence reducing overreliance on bank funding and thereby spurring competition in the credit market, which would eventually lead to cheaper debt costs for borrowers,

- Addressing the tax advantages that banks enjoy: Level the playing field by making tax incentives available to banks to be also available to non-bank funding entities and capital markets products such as unit trust funds and private investment funds. For example, providing alternative and capital markets funding organizations with the same withholding tax incentives that banking deposits enjoy, of a 15% final withholding tax so that depositors don’t feel that they have to go to a bank to enjoy the 15% withholding tax; alternatively, normalize the tax on interest for all players to 30% to level the playing field,

- Consumer education: Educate borrowers on how to be able to access credit, the use of collateral, and the importance of establishing a strong credit history,

- The adoption of structured and centralized credit scoring and rating methodology: This would go a long way to eliminate any biases and inconsistencies associated with accessing credit. Through a centralized Credit Reference Bureau (CRB), risk pricing is more transparent, and lenders and borrowers have more information regarding credit histories and scores, thus enabling banks price customers appropriately, spurring increased access to credit,

- Increased transparency: This can be achieved through a reduction of the opacity in debt pricing. This will spur competitiveness in the banking sector and bring a halt to excessive fees and costs. Recent initiatives by the CBK and Kenya Bankers Association (KBA), such as the stringent new laws and cost of credit website being commendable initiatives,

In conclusion, a free market, where interest rates are set by market participants coupled with increased competition from non-bank financial institutions for funding, will see a more self-regulated environment where the cost of credit reduces, as well as increased access to credit by borrowers that have been shunned under the current regime. Consequently, a repeal is necessary, but the repeal needs to be comprehensive and contain the 7 elements above for it to be effective, but the center-piece of the legislation should be stimulating capital markets to reduce banking sector dominance, yet this key piece seems to be missing in the current draft discussions.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the writers where particulars are not warranted. This publication, which is in compliance with Section 2 of the Capital Markets Authority Act Cap 485A, is meant for general information only and is not a warranty, representation, advice or solicitation of any nature. Readers are advised in all circumstances to seek the advice of a registered investment advisor.