Dec 27, 2020

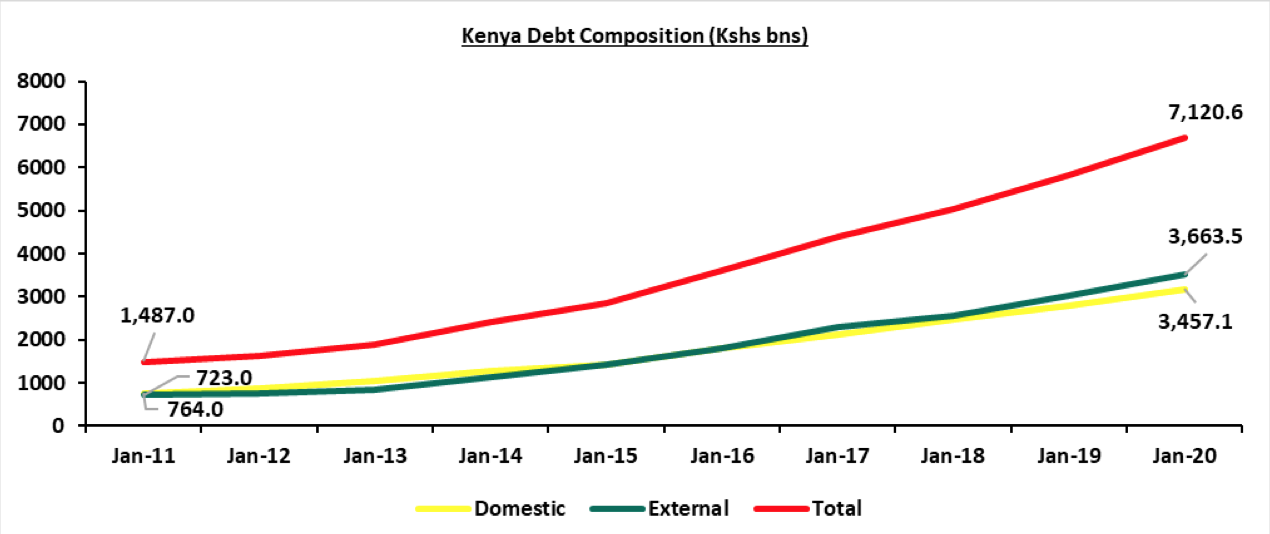

Over the past few years, Kenya’s Public Debt has been on the rise, increasing from Kshs 1.3 tn 10 years ago to Kshs 7.1 tn now, at a 10-year CAGR of 18.5%. The rising debt has been brought about by the government’s significant borrowing to fund infrastructural projects and bridge the fiscal deficit that has averaged 7.7% of GDP since 2012, with borrowing being both direct and also by guaranteeing state corporations. The debt mix currently stands at 51:49 external to domestic debt, respectively, compared to 45:55 external to domestic debt 10 years ago. With the current pandemic, the revenue collections have also been lagging and we expect more borrowing to bridge the gap, evidenced by the government’s plan to borrow USD 2.3 bn (Kshs 256.2 bn) loan from the IMF and up to USD 1.5 bn (Kshs 167.1 bn) from the World Bank. Key to note, the IMF had approved a USD 739.0 mn (Kshs 78.4 bn) disbursement to be drawn under the Rapid Credit Facility in May, in addition to USD 1.0 bn (Kshs 106.1 bn) financing received from the World Bank in the same month to help the country respond to the sudden economic shock at the onset of the pandemic. The 9 months following the reporting of the first case of Covid-19 have seen public debt rise to new highs driven by several factors which include but are not limited to:

- Reduction in government revenue for the first quarter of FY’2020/21, with revenue collection being Kshs 100.8 bn lower than at the same period last year, being at Kshs 527.7 bn compared to Kshs 628.5 bn collected in the same period last year. The low collection can be attributed to the significant weakening of economic activity as a result of containment measures by the government in addition to the tax incentives put in place to cushion the economy against the adverse effects of the pandemic. Key to note, however, some of the tax measures put in place to cushion the economy will revert to pre-Covid rates on January 1st 2021. These include:

- Corporate Tax rate which was reduced to 25.0% from 30.0%,

- Individual Income Tax rate for individuals earning higher than Kshs 24,000, which was reduced to 25.0% from 30.0%, and,

- Value Added Tax (VAT) rate which was reduced to 14.0% from 16.0%,

- Parliament’s approval of a proposal by the National Treasury in October 2019 to raise the national debt ceiling to an absolute figure of Kshs 9.0 tn from the previous limit of 50.0% of the GDP which has given the government more room for borrowing, and,

- Continued servicing of commercial loans and Eurobonds, denominated in US dollars, despite a weakening shilling which has depreciated by 7.4% YTD to stand at Kshs 108.8 against the dollar as at 24th December 2020,

We have been tracking the evolution of the public debt and below are the previous topicals we have done on Kenya’s debt:

- Kenya’s Debt Levels: Are we on a Sustainable Path?– In May 2016, we wrote about the rising debt levels in the country and concluded that they were within the safer bounds in terms of debt levels but needed to look into risks associated with the changing funding patterns that could see the debt levels rise,

- Kenyan Debt Sustainability– In December 2016, we wrote about Kenya’s debt level, questioning its sustainability, and concluded that the government needed to reduce the amount of public debt, giving suggestions as to how this could be achieved,

- Kenya’s Public Debt, Should We be concerned? – In February 2018, we wrote about the concerns surrounding the debt level of the country and concluded that we should be concerned about the country’s debt levels unless decisive policies were implemented, and,

- Kenya’s Public Debt – In July 2020, we wrote about the high debt levels in the country, which have exceeded the recommended threshold, and the downgrading of Kenya’s creditworthiness on the back of an economic downturn following the global pandemic and we gave suggestions on measures that could be taken towards debt sustainability,

In this week’s topical, we focus on the current state of affairs regarding the country’s public debt profile and levels and discuss how sustainable the same is. Under this, we shall cover:

- Kenya’s Evolution of Debt,

- Kenya’s Current Debt Levels, Debt Profile and Composition,

- Analysis of debt metrics

- Debt management strategies put in place, risks abound and recommendations going forward

- Conclusion

Section II: Current Debt Levels and Evolution of Debt

The country’s total public debt as at 30th September 2020 stood at Kshs 7.1 tn (equivalent to 69.6% of GDP), which is a Kshs 1.2 tn increase from the Kshs 6.0 tn debt recorded in September 2019 (equivalent to 62.1% of GDP). Parliament approved to increase the debt ceiling to the absolute figure of Kshs 9.0 tn from the initial 50.0% of GDP in October 2019, meaning that the government has headroom to borrow an additional Kshs 1.9 tn before the current debt ceiling is exceeded. Key to note, since the first reported case of COVID-19 on 13th March 2020 in Kenya, the total public debt has grown by 13.3% to Kshs 7.1 tn from Kshs 6.3 tn. The debt mix currently stands at 51:49 external to domestic debt, respectively, with foreign borrowing at Kshs 3.7 tn while domestic borrowing stands at Kshs 3.5 tn. Banking institutions account for the highest percentage of domestic debt in terms of government securities holdings at 53.9%.

Below is a table of the composition of government domestic debt by holder:

|

|

Composition of Government Domestic Debt by Holder |

||||||||||

|

|

Dec-10 |

Dec-11 |

Dec-12 |

Dec-13 |

Dec-14 |

Dec-15 |

Dec-16 |

Dec-17 |

Dec-18 |

Dec-19 |

Dec-20 |

|

Banking Institutions |

55.1% |

47.3% |

52.6% |

48.2% |

54.0% |

55.8% |

52.2% |

54.3% |

54.5% |

54.2% |

53.9% |

|

Insurance Companies |

10.5% |

11.7% |

10.5% |

10.3% |

9.9% |

8.4% |

7.2% |

6.4% |

6.1% |

6.5% |

6.4% |

|

Parastatals |

6.8% |

6.5% |

4.8% |

3.6% |

2.8% |

4.7% |

5.9% |

6.9% |

7.3% |

6.7% |

5.7% |

|

Pension Funds |

20.6% |

29.2% |

20.3% |

26.6% |

24.0% |

25.2% |

28.1% |

27.8% |

27.6% |

28.2% |

29.8% |

|

Other Investors |

7.0% |

5.3% |

11.8% |

11.3% |

9.3% |

5.9% |

6.5% |

4.5% |

4.6% |

4.4% |

4.3% |

|

Total |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

Source: Central Bank of Kenya

Below is a table highlighting the trend in the external and domestic debt composition over the last 10 years;

Source: Central Bank of Kenya

Debt composition and Evolution:

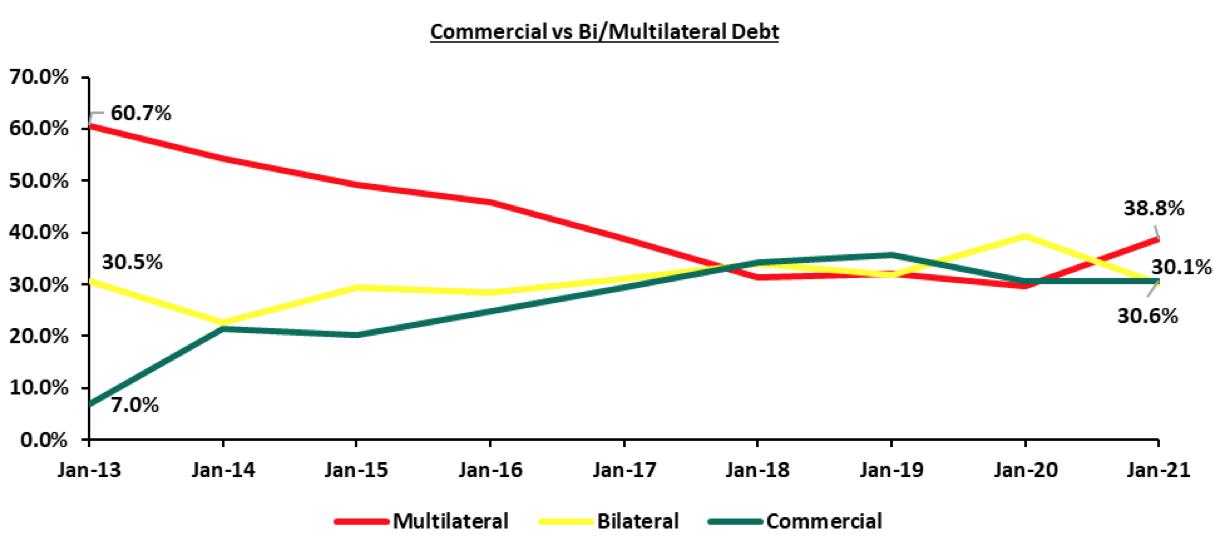

The country’s debt composition has evolved, with the government increasing foreign debt to Kshs 3.7 tn as at September 2020 compared to Kshs 0.6 tn in September 2010, at a 10-year CAGR of 20.0%, while domestic debt has increased to Kshs 3.5 tn as at September 2020 compared to 0.7 tn in September 2010, a 10-year CAGR of 17.5%. Foreign debt has therefore increased at a faster rate than domestic debt, highlighting that the government is turning more to external lenders. Foreign debt comprises of multilateral loans, bilateral loans and commercial loans. Multilateral loans are debts issued by international institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF to member nations to promote social and economic development while bilateral loans are loan agreements between individual nations. Multilateral and bilateral loans are categorized as concessional loans due to the favourable terms offered in terms of either below-market interest rates, long grace periods or a combination of both. Commercial loans, on the other hand, are loans agreed between a country and an external commercial bank or an external financial debt instrument. Commercial loans typically have higher rates and shorter grace periods.

Kenya’s exposure to bilateral and multilateral loans has been declining in favour of a much more commercial funding structure comprising of Eurobonds and syndicated loans (loans provided by a group of lenders who work together to provide funds for a single borrower). This has seen the proportion of concessional loans (Bilateral and Multilateral debt) which stood at 79.8% of total external debt as at September 2015, decline by 10.9% points to approximately 68.9% of total external debt as at September 2020. Commercial loans, deemed more expensive because of their high-interest costs, have grown at a 5-year CAGR of 30.5% from a low of Kshs 295.6 bn (equivalent to 19.1% of total external debt) as at September 2015, to Kshs 1.1 tn (equivalent to 30.6% of total external debt) as at September 2020. It is key to note that:

- Multilateral debt increased by 9.1% points to 38.8% in September 2020 from 29.7% of total external debt in June 2020 due to loans from the IMF and the World Bank received during the period. Bilateral debt decreased by 1.0% points to 30.1% in September 2020, from 31.1% in September 2015, and,

- Commercial debt has cumulatively increased by 11.5% points to 30.6% of total external debt in September 2020 from 19.1% in September 2015, mainly attributable to the issue of Eurobonds within the period,

This is illustrated in the chart below:

Source: Central Bank of Kenya & National Treasury

Section III: Debt Metrics

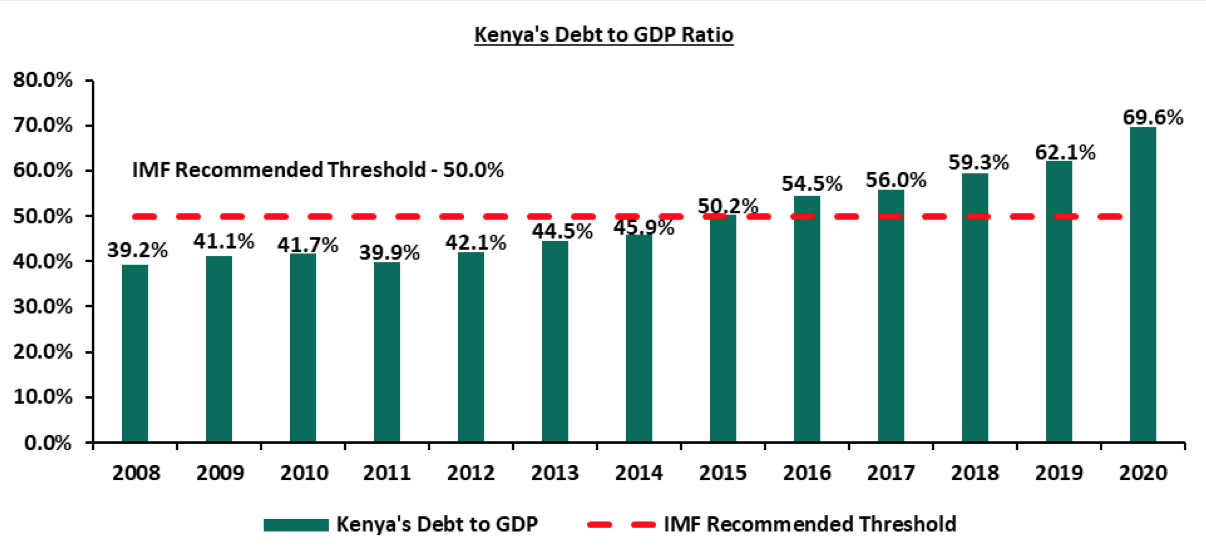

- Debt to GDP Ratio

Kenya’s debt to GDP ratio came in at an estimated 69.6% in 2020, 15.6% points above the IMF recommended threshold of 50.0% for developing countries. Late last year, the treasury amended the Public Finance Management (PFM) regulations to substitute the debt ceiling which was previously set at 50.0% of GDP to an absolute figure of Kshs 9.0 tn to plug the budget shortfalls. As highlighted in our focus on Kenya’s Public Debt in July, according to Fitch Ratings, the shocks from COVID-19 are expected to delay the narrowing of the fiscal deficit. Government debt is forecasted to reach 70.0% of GDP in 2021 on the back of rising debt levels and weak revenue growth. Below is a graph highlighting the trend in the country’s debt to GDP ratio;

Source: World Bank

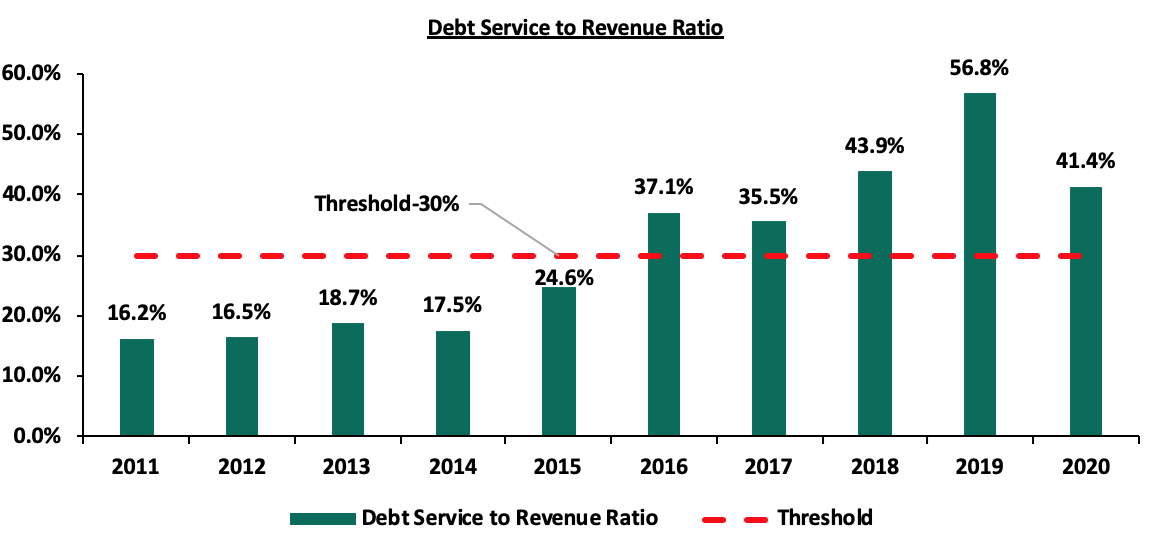

- Debt Service to revenue

This is a measure of how much of the government’s revenue is used to service debt. For the first half of 2020, revenue collection activities of the government have been affected due to the ongoing pandemic with major economic sectors such as tourism, manufacturing and agriculture bearing the brunt of the effects of the pandemic following supply-side shocks. According to the National Treasury’s Annual Debt Management Report 2019/2020, the debt service to revenue ratio is estimated at 41.4% at the end of 2020, 11.4% points higher than the recommended threshold of 30.0% but 15.4% points lower than FY’ 2019’s debt service ratio of 56.8%, attributable to reduced debt service obligations during the year. The reduction in service obligations in 2020 compared to 2019 is attributed to the country retiring the Kshs 75.0 bn debut Eurobond floated in 2014 in FY’ 2019/2020. This payment was however serviced using funds from the Kshs 210.0 bn dual-tranche 7-year and 12-year Eurobond issued the same year. The sustained level of debt service to revenue ratio above the recommended threshold is a worrying sign, elevating the refinancing risk following shocks arising from the ongoing pandemic and low revenue collection. For this financial year, a total of Kshs 651.5 bn has been set aside for debt servicing from the targeted Kshs 1.6 tn revenue collection. Below is a chart showing the debt service to revenue ratio;

Source: National Treasury Annual Public Debt Report

Further to the above, we expect the country’s cost of debt servicing to rise driven by currency depreciation with the shilling having depreciated by 7.4% year to date to close the week at Kshs/USD 108.8. This means that as the shilling depreciates, the government will have to pay more to service its foreign-denominated external debt. Additionally, the debt service to revenue ratio is expected to increase mainly driven by the expected decline in revenue. The table below shows the comparison of the currency composition of foreign debt in June 2020 compared to June 2014:

|

Currency composition of External Debt end June 2020 |

||

|

Jun-14 |

Jun-20 |

|

|

USD |

42.8% |

67.3% |

|

Euro |

28.5% |

18.0% |

|

Japanese Yen |

11.5% |

6.6% |

|

Chinese Yuan |

4.8% |

5.4% |

|

GBP |

4.7% |

2.5% |

|

Others |

7.7% |

0.2% |

|

Total |

100.0% |

100.0% |

Source: National Treasury Annual Public Debt Report

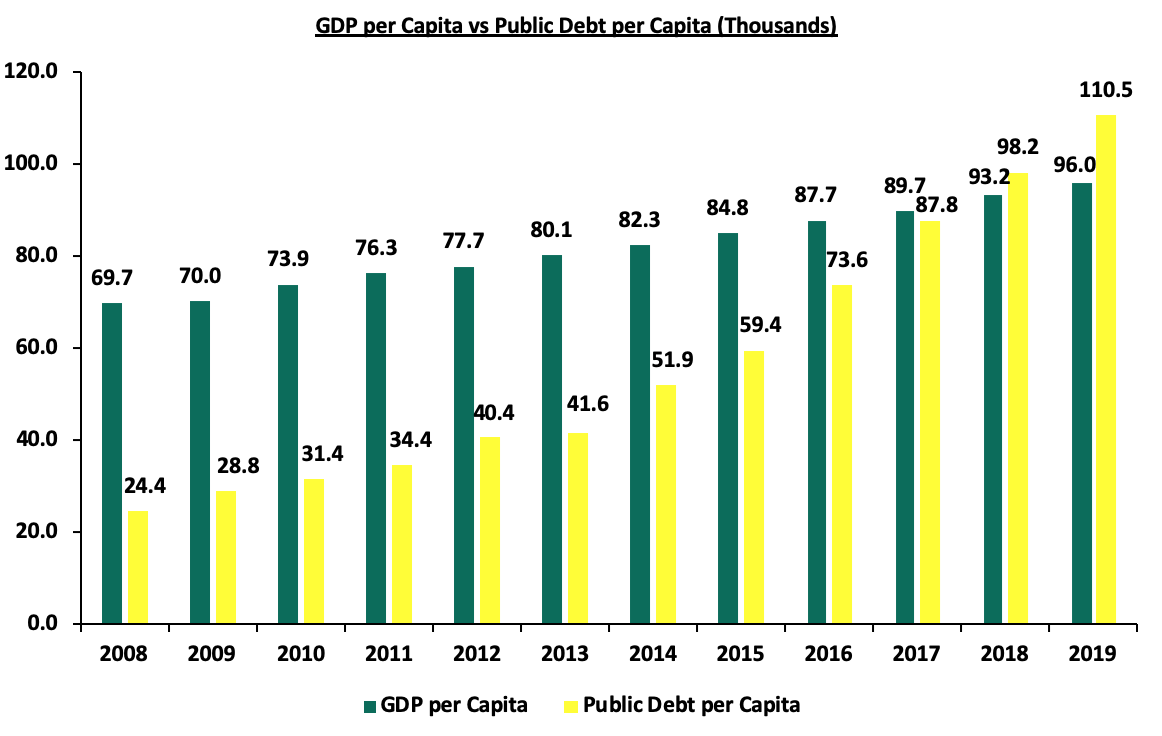

- GDP per Capita vs Debt per Capita

Kenya’s Public Debt per Capita has increased at an 11-year CAGR of 14.7% from FY’2008 to FY’2019, compared to GDP per Capita which has grown at an 11-year CAGR of 3.0%. This is an indication that public debt is rising at a faster rate than the GDP, further elevating the risk of debt distress and may also be an indication that the debt being incurred is not translating into economic growth. The Debt per Capita, which can be viewed as an indicator of the average debt burden on an individual citizen, currently stands at Kshs 110,472.9, which is Kshs 14,430.9 higher than the GDP per Capita, which currently stands at Kshs 96,042.0, according to World Bank data.

Source: World Bank and Central Bank of Kenya

Section IV: Debt Management Strategies and Recommendations going forward

During the financial year, the National Treasury, through the Public Debt Management Office (PDMO), formulated the Public Debt and Borrowing Policy, which was approved by the cabinet in March 2020, to strengthen and guide the management of public debt. The objectives of the Public Debt and Borrowing Policy include:

- Ensure government financing needs and payment obligations are met at the lowest possible cost over the medium to long-run, consistent with a prudent degree of risk,

- Promote the development of the domestic debt market through a partnership with the Kenya Bankers’ Association by establishing an Over-The-Counter (OTC) platform to improve liquidity in Kenya’s debt market

- Provide guidance to the treasury on debt management and contraction of public debt

- Ensure value for money from debt-funded programs

- Safeguard the country’s debt sustainability

In addition to the Public Debt and Borrowing Policy, the government is also considering the G-20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) which would see the country benefit from up to Kshs 75.0 bn in suspended debt service obligations (7.0% of total debt). The DSSI, however, doesn’t involve commercial creditors or some bilateral lenders such as China, which accounts for 28.0% of foreign bilateral trade. The DSSI is being offered as a condition to secure additional funds from the IMF, but it would only offer a short term solution and possibly lead to the further downgrading of Kenya’s credit rating by international credit rating institutions, consequently increasing the cost of debt. The government, therefore, finds itself between a rock and a hard place as it weighs its options. According to a clause in the Eurobonds II Prospectus, external debt suspension of foreign-denominated debt of any form is taken as default, and as such, the holders of at least 25.0% of the bond may declare all the Notes to be immediately due and payable at their principal amount together with the accrued interest. This is a situation the government isn’t willing to get into, hence the hesitation of joining the DSSI.

Due to sub-optimal revenue collection owing to the subdued business environment caused by the containment measures put in place to curb the spread of Covid-19, the government has found itself in a position where it has to borrow more funds to plug the fiscal deficit. Below are some of the risks that the high debt levels open the economy to:

- Further depreciation of the local currency, which hit an all-time low of Kshs 111.6 against the dollar on 15th December as other governments demand hard currency to service the debt increases,

- The higher cost of debt servicing due to debt obligations in foreign currencies despite a weakening shilling, which may lead to higher taxation as the government tries to keep up with its debt obligations,

- The increased cost of further borrowing since lenders will price the new debt at higher rates considering the possible increased risks,

- Crowding out of the private sector by the government which largely leads to lower projected economic growth, subsequently impacting collections further, and,

- Fiscal consolidation and austerity measures which undermine economic activity, development objectives and decrease the government’s ability to effectively respond to emergencies since governments often borrow to address unexpected events. Having a high debt level means there will be fewer options,

Recommendations

The high debt levels in the country have become a point of great concern with both the debt to GDP ratio as well as the debt service to revenue ratio having exceeded the recommended thresholds. We expect the economy to face fiscal challenges arising from the global pandemic. This sentiment has been echoed by various authoritative bodies, pointing to a possible further downgrading of Kenya’s creditworthiness. Despite this, some investors are optimistic with regards to the country’ outlook evidenced by the decline in Eurobond yields since May, pointing to the perception of lower risk in the country going forward, coupled with the additional funding received from both the World Bank and the IMF. Locally, the Central Bank, through the Monetary Policy Committee, has continued to support the economy through the policy rate and the Cash Reserve Ratio and is confident that the measures put in place are having the desired effect. Below are some actionable steps the government can take towards debt sustainability;

- Restructuring the debt mix towards more concessional borrowing: the government should go for more concessional borrowing to reduce the amounts paid in debt service. Additionally, commercial borrowing should be limited to development projects with high financial and economic returns, to ensure that more expensive debt is invested in projects that yield more than the market rate charged,

- Reduce capital expenditure: The government can carry out capital expenditure cuts during the current period of distress and direct the funds to areas that have a higher economic return such as supporting the agricultural and manufacturing sectors. By scaling down on the funding of new projects and focusing on completing those that are pending, the economic benefits will be transmitted into the economy and support overall economic growth. Feasibility tests should also be done before embarking on mega-infrastructure projects to ascertain their Economic Rate of Return (ERR) to ensure the economic benefits outweigh the cost and the ripple effect from the projects will provide an enabling economic environment to facilitate servicing the debt instead of saddling the servicing burden on taxpayers,

- Build an export-driven economy: The government can focus on developing certain sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing to build an export-driven economy. Encouraging growth in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors will help increase the value of our exports, leading to an improved current account. Additionally, they can encourage private sector involvement in such development projects to reduce the strain on government expenditure, and,

- Private-Public Partnerships for projects: Establishing Private-Public partnerships to facilitate infrastructural projects and reduce the reliance on borrowing to fund projects. The recently launched Kenya Pension Funds Investment (KEPFIC), that allows pension funds to invest up to 10.0% of their Assets Under Management (AUM) on infrastructure and alternative investments is a step in the right direction in this regard since it will not only reduce the infrastructural burden of debt but also deepen and enhance the capital market,

Section V: Conclusion

The current level of debt is worrying which has further been exacerbated by the weak economic fundamentals attributable to the effects of COVID-19 pandemic. Q2’2020 GDP growth contracted by 5.7%, the first contraction since Q3’2001 when the economy contracted by 2.5%, the 2020 contraction was due to the closure of schools and contraction in education output, which contributed a 1.7% points reduction in GDP, contraction in the services sub-sector which contributed a 1.4% points contraction and reduced government revenue from taxes, which weighed down GDP growth by 0.6% points. According to the IMF, GDP growth is however expected to come in at 1.0% in 2020 and rebound to 4.7% in 2021 owing to the gradual reopening of schools and the global economy, favorable rains and consequently improve agricultural output.

A significant amount of government spending has gone towards development projects whose expected economic return might not be able to finance the cost of financing. For example, the Exim Bank of China is set to receive Kshs 43.2 bn in debt payments for the SGR in the current fiscal year despite the project facing a variety of challenges such as low cargo volumes and revenue shortfalls. In the period from January to May 2020, the SGR recorded revenues of Kshs 4.9 bn against operation costs of Kshs 7.3 bn, representing a loss of Kshs 2.4 bn. This means that instead of the high-cost project contributing to its debt servicing, the burden is falling entirely on the taxpayer; an indication that a significant part of growth in debt is not translating into growth in the economy.

The coming financial year will likely see the government cut back on expenditure and focus on fiscal consolidation as it aims to reduce the budget deficit. The austerity measures that are likely to follow will negatively affect the economy, which requires stimulus as it recovers from the adverse effects of the pandemic. Limited government expenditure will also work against the governments ambitious ‘Big 4 agenda’ and limit the ability of the government to provide public services. We are of the view that suspending debt obligations would not solve the problem but instead exacerbate the issue by increasing servicing pressure once the suspension period is over since the government will then have to service more expensive commercial loans in addition to the servicing the suspended obligations.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the writers where particulars are not warranted. This publication is meant for general information only and is not a warranty, representation, advice or solicitation of any nature. Readers are advised in all circumstances to seek the advice of a registered investment advisor.